Former head of the British Army Sir Michael Jackson has

admitted last month innocent people were killed in Derry’s Bloody Sunday massacre of 1972. Jackson made the admission in an interview with BBC Northern Ireland's flagship current affairs program, Spotlight. However the former army chief, who was a captain with the parachute regiment in Northern Ireland at the time, said people should wait for the outcome of the latest Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday before making judgements.

Bloody Sunday was one of the defining moments of Northern Ireland’s 30 year conflict. British troops shot dead 14 unarmed Catholic civilians (13 died immediately, and one later from injuries) on 30 January 1972 ending any lingering hopes in Nationalist community the British army were anything other than an occupying force. The incident is covered in detail in an excellent book “

Brits: the War against the IRA” by British journalist Peter Taylor. Brits is the third book in his trilogy on the war. The first, “Provos”, told the story from the nationalist side, the second “Loyalists” told story of Protestant unionism and Brits takes the army perspective.

The book chronicles its involvement, and most intriguingly, its intelligence operation, during the 30 year conflict. The book tells how the army’s most secret undercover surveillance unit in the province,

14 Intelligence Company, known as the Detachment, or ‘Det’, played a major role in bringing the IRA to the negotiation table. With the help of technology, surveillance and undercover operators, the ‘Det’ almost crippled the IRA by the end of the 1980s and made its leadership see only a political settlement could win the war.

Northern Ireland was created by Westminster’s

Government of Ireland Act 1920. Ireland was divided into two partitions each with its own home rule government. The north was to be a Protestant state for a Protestant people. A new boundary was drawn around the ancient province of Ulster but with the three Catholic majority counties (Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan) removed. In the new state of Northern Ireland, discrimination was endemic. Derry council was gerrymandered so 14,000 Catholic voters elected eight councillors while 9,000 Protestant voters elected 12. Harland & Wolff, builders of the Titanic, employed 10,000 workers on its Belfast dockyards but only 400 were Catholic. Northern Ireland had its own Protestant-dominated parliament at Stormont while Westminster devoted just two hours a year discussing Northern Irish issues.

Decades of Catholic resentment blew up in the seminal rebellion year of 1968. A new breed of charismatic leaders like

Bernadette Devlin and John Hume demanded change and universal civil rights. The Protestants saw the civil rights movement as an IRA front and treated it with suspicion. In October, TV news brought pictures of a civil rights march baton charged by police. The incident confirmed the Catholic belief the Royal Ulster Constabulary were another sectarian force. Violence grew in Derry and spread to Belfast by the summer of 1969. The Protestant Apprentice Boys march in August caused a full scale riot in Derry that lasted three days and found the RUC ill-prepared to deal with the problem. With the situation deteriorating on the third day, the First Battalion of the Prince of Wales Own Regiment of Yorkshire was drafted in. It was the first deployment of troops on the street.

The troops were welcomed by the Catholics who saw the army was there to stop them from being bashed by police. But just as the situation calmed in Derry, large-scale violence broke out in Belfast along sectarian lines. Vicious street fights broke out between nationalists and police and nationalists and loyalists. The IRA got involved and shot dead a policeman Herbert Roy. The RUC shot dead three Catholics as loyalist mobs torched Catholic houses in streets they shared. After several days, police admitted defeat and called in the army. Troops were flown in and needed to buy maps of Belfast at the airport. Most soldiers saw their mission as stopping Protestants from burning out Catholic homes.

Meanwhile the IRA was in turmoil. While some members fought in the riots, the official line was to steer clear of the trouble having declared a ceasefire. Graffiti appeared saying “IRA – I Ran Away”. Divisions in the IRA hierarchy were formalised and a new group called the Provisional IRA (“Provos” for short) re-affirmed the right to achieve a united Ireland by violent means.

The army enforced an uneasy peace line between the Catholic and Protestant communities. But the marching season would change all that. At Easter 1970 a group of Orangemen began their day out by marching past the Catholic Belfast community of

Ballymurphy. The Catholics were waiting for them and a two-hour full scale riot ensued. Confused soldiers stood hapless in the middle. The following day, the army decided on a show of force in expectation of a continuation of the riot. They arrived in armoured cars loaded with rifles, riot shields and CS gas. The Catholics redirected their missiles to this new enemy and the army hit back firing CS gas. With rioting continuing all night, the army baton-charged and the Protestants followed in their wake, confirming suspicions the army was on their side. Army leader General Sir Ian Freeland confirmed there was a ‘get tough’ policy. The Ballymurphy riots were the real starting point of the war. The provisional IRA now had an enemy they could fight.

On 27 June, they sprang into action after another Protestant march in Belfast. Missiles were exchanged and the IRA brought out their guns killing three Protestants. They fought a gun battle later that night in East Belfast and killed two more. They could now claim to be the defenders of Catholic areas. The new Tory government in Westminster demanded strong action and imposed a 35 hour curfew in the Falls area while the army conducted house-to-house searches. While the military objective was successful and discovered a hoard of weapons, the IRA had won the hearts and minds of the occupants who now knew the British Army as the sworn enemy.

The two sides kept up a dialogue despite the violence. In February 1971 Major-General

Anthony Farrar-Hockley, the commander of British land forces, went on TV and named the leaders of the IRA as Billy McKee, Frank Card, Leo Martin and Liam and Kevin Hannaway. The “named and shamed” men immediately went into hiding. The day after, the IRA shot its first British soldier in a riot, Gunner Robert Curtis from Newcastle. On the day after, Stormont Premier James Chichester-Clark declared Northern Ireland was at war with the IRA. The IRA soon shot three more soldiers. They were off-duty, wearing civilian clothes and drinking at a bar. They were invited to a party and then shot on a lonely road. It was the end of détente between the army and the community.

By August 1971, ten soldiers were dead and the IRA had launched over 300 explosions. The government began to look at internment as a solution. They found an old army depot used to store Land Rovers and trucks at a place called “

Long Kesh” outside Belfast. The place was spruced up and turned into an internment camp. Operation Demetrius was put into place to swoop through Nationalist areas in a dawn raid. Dustbin lids banged through the city as women warned the men the army was coming. The army arrested 341 republican suspects but no loyalists. The last vestige of even-handedness was shattered.

Some of those arrested were subject to torture. They were guinea pigs of what was called the

Five Techniques, imported from the Army’s experience in counter-insurgency in the colonies and learned from the North Koreans. The techniques were: making suspects stand against a wall with arms spread-eagled for hours at a time, placing hoods over their heads to produce sensory deprivation, subjecting them to continuous ‘white noise’ to disorientate, and depriving them of sleep and food. But the problem was that although the techniques were successful, internment wasn’t – most of the IRA leadership had evaded the search.

The death toll soared. The IRA killed two people and the army killed 16. The army ended no-go areas in Belfast but they still existed in Derry. The IRA had 29 barricades set up, 16 of which were impassable to one-ton armoured vehicles. Despite Protestant outrage, the army maintained a policy of containment. But a secret army memo was about to change that. The army looked for a way to penetrate hostile areas and restore ‘the rule of law’. The excuse was an anti-internment march planned for Sunday 30 January 1972. 20,000 people marched into the city but was blocked from getting to city council buildings. Marchers threw missiles at the army; an IRA man fired one bullet and the army fought back. By the end of the day 13 unarmed Catholics were dead and another was dying. The soldiers’ actions were exonerated by the whitewashing of the

Widgery Report and it wasn’t until 1998 that Tony Blair instituted the Saville Inquiry. That report has yet to be handed down.

Bloody Sunday was the pivotal event of the war. It gave the Provos a huge propaganda victory and a new moral authority to fight their war. It also ended the Protestant regime. In March 1972 Britain suspended Stormont and introduced Direct Rule. That same month, the IRA exploded its first car bomb in Belfast, a 112kg bomb which killed seven people in Donegall Street and injured 150. Yet the two sides also conducted talks. Gerry Adams was released from internment and he and fellow IRA man David O’Connell met two British intelligence officers in June. There followed a second meeting in London between top officers including IRA president

Sean MacStiofain (originally an Englishman named John Stephenson), and the newly appointed Northern Ireland secretary Willie Whitelaw. The meeting was an impasse and the IRA re-intensified its campaign.

On 21 July, the IRA planted 22 bombs in Belfast and killed nine people on a day that became known as

Bloody Friday. The army began a new campaign in response; an intelligence operation to get under the IRA’s skin. They ran a bogus laundry service known as “Four Square laundry”. Its drivers drove around republican areas and returned washing to its clients. While the laundry was genuine, other activities weren’t. Clothes were tested forensically for traces of explosives. The operation was undone when the IRA ‘turned over’ an informer who spilled the beans. They ambushed the van and killed the driver. The army knew it needed more sophisticated techniques to break the IRA.

The army began recruiting spies. The ‘Det’ was established with a hand-picked elite to staff it. There were three detachments, based in Belfast, Derry and Armagh. The ‘Det’ relies on paid informers from within the Nationalist community. The IRA was in crisis in 1973 as improved relations with Irish police saw the arrest of leaders such as MacStiofain,

Martin McGuinness, Martin Meehan and John Kelly. The IRA planted its first bombs in England, exploding two car bombs in London after which one person died from a heart attack. The ‘Det’ had its first major victory when it arrested three leaders; Gerry Adams, Brendan Hughes and Tom Cahill in an IRA safe house. Hughes later escaped from prison wrapped up in a mattress left out for rubbish. He returned incognito to Belfast where he directed IRA operations until ‘Det’ surveillance nabbed him a second time.

There was movement too in the political sphere. The Irish and British governments met in December 1973 in Sunningdale, Berkshire and created a power-sharing executive for the North. The new government came into place in 1974 but was immediately opposed by Protestant hardliners. Workers who ran the province’s economy and public utilities organised a general strike under the banner of the

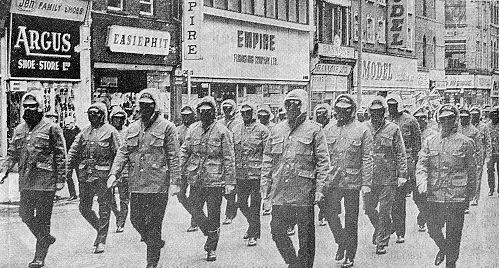

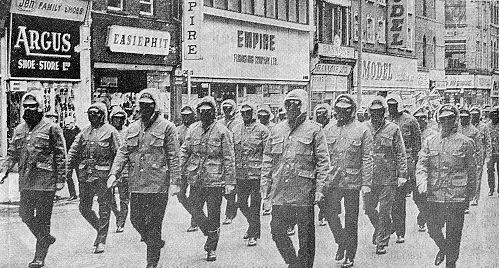

Ulster Workers Council. They manned barricades and intimidated opponents as well as shutting down the power grid. Prime Minister Harold Wilson vilified the strikers on TV which further hardened attitudes. Three days later the executive resigned and Direct Rule was re-introduced. The Sunningdale agreement was destroyed; the UWC had won.

While the strike was in progress, MI6 appointed a new man in Northern Ireland

Michael Oatley who would become a key, if unrecognised, figure in the years to come. Oatley's job was to make contact with the IRA leadership. One contact was called a ‘pipe’ which linked with the IRA’s new leader Ruari O’Bradaigh. Through the pipe, the British were getting indications that the Provos wanted to talk.

The pressure was building as the UVF stepped up their anti-republican campaign. On 17 May 1974, they planted car bombs in rush hour in Dublin and Monaghan which exploded without warning. They killed 33 people and injured 160 others. The IRA was also active in England. They bombed two pubs in Guildford, Surrey used by off-duty soldiers. Four soldiers and a civilian were killed. They then bombed two pubs in

Birmingham killing 21 and injuring 182. Britain was outraged and introduced the Prevention of Terrorism Act under which suspects could be held for seven days and ‘exclusion orders’ could keep people out of mainland Britain.

The IRA Active Service Unit continued to cause havoc in the 12 months that followed, bombing indiscriminate targets in London and causing terror in the population. They killed Guinness Book of Records founder and outspoken IRA critic

Ross McWhirter before finally being caught in a siege in Balcombe St which lasted six days before they surrendered. The four members of the Balcombe St gang were released as part of the Good Friday agreement in 1998.

Harold Wilson sent in the SAS in a blaze of publicity in 1976. Their actions were immediately controversial as they followed suspects across the border. They also kept a covert observation post on the Irish side of the border. Eight SAS officers in two cars were arrested by Irish police in what the British authorities called as a “map reading error”. But it was their ‘

shoot to kill’ policy which saw the IRA rename them as “Special Assassination Squad”. Among their victims was Patrick Duffy, an unarmed IRA man who was shot dead with a dozen bullets in his own home.

On 27 August 1979, the IRA struck two devastating blows in return. The Queen’s cousin, Earl Mountbatten, was

blown up on a boat at his holiday home in Sligo. A few hours later two massive explosions at Warrenpoint, County Down they killed 18 soldiers, 16 of them members of the Parachute Regiment 2nd battalion. It was the regiment’s biggest loss since Arnhem in World War II.

Under Labour in 1976 the political status of IRA prisoners was revoked and they were to be treated as ordinary criminals. They were sent to the newly constructed

H Blocks of the Maze Prison at Long Kesh. The prisoners launched a ‘dirty protest’ in response, refusing to wear prison issue clothes or leave their cells. They also smeared the walls of their cells with excrement.

By 1979, Margaret Thatcher was in power. She was disinclined to deal with the demands of the prisoners. The prisoners launched a hunger strike which ended without a deal. They launched a second hunger strike in which ten prisoners died.

Bobby Sands, the first of those to die, was elected MP in a sudden by-election on the 40th day of his strike. The result gave the IRA a new political impetus it was to exploit in the decades to follow. 100,000 people attended Sands’ funeral. The IRA called off the strike after it was obvious it was not changing Thatcher’s mind. Within a few years they got all their demands anyway.

In October 1982, three RUC officers were killed in a bomb after they were called to investigate a suspicious hayshed. The shed was under surveillance by M15 but the officers had not spotted the bomb. An informer named the two IRA men responsible and they and another man were shot dead by police who were exonerated by the courts for ‘bringing three IRA men to the final court of justice’. After intelligence forces shot an innocent 16 year old at the same hayshed,

John Stalker, deputy Chief Constable of Greater Manchester was brought in to investigate the shoot to kill policy. He wanted to see a copy of the tape at the hayshed but was denied access. He was removed from the inquiry due to his association with a Manchester businessman Kevin Taylor who was erroneously thought to be a criminal. Though Stalker’s replacement recommended charges be brought, Attorney-General Sir Patrick Mayhew said there would be no prosecutions “in the national interest”. The prospect of MI5 officers in the dock was avoided.

Throughout the eighties, the ‘Det’ continued their stranglehold on the IRA. The IRA was forced to act in Britain where the intelligence network wasn’t as strong. But the IRA needed to acknowledge a change. In 1981,

Danny Morrison made a famous speech at a Sinn Fein conference that “with a ballot box in one hand and the Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland”. His speech would define Sinn Fein policy for the next 15 years. Adams, McGuinness and Morrison all won seats in the new Northern Ireland Assembly in 1982 with 10 per cent of the vote. The main nationalist party the SDLP took 18.1 per cent.

In 1984, the IRA had its highest profile hit with the

Brighton bombing. The ruling Tories were staying at the Grand Hotel for their annual conference. The IRA planted a 9kg bomb which exploded during the night collapsing four floors of the hotel. Five Tory party members were killed including Sir Anthony Berry MP. But Thatcher survived and received an eight minute ovation at the conference in the morning. The IRA issued a chilling message which read partially “Today we were unlucky, but remember we only have to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always”. After an astonishing piece of detective work, the bomb was traced to Patrick Magee who was arrested in Glasgow ten months later. Magee was released as part of the Good Friday Agreement with a doctorate in Irish studies after a dissertation on how Gerald Seymour, Tom Clancy and others fictionalised the conflict.

The SAS continued their operation against the IRA with victories in Loughgall which killed an ASU about to hit a RUC station and then in Gibraltar where three IRA operatives were gunned down. At their funeral in Belfast, a Loyalist gunman Michael Stone

opened fire and killed three mourners. British TV investigated the Gibraltar deaths and concluded the three had been shot with their hands up. Thames TV showed the program despite Thatcher’s fury.

The IRA received a boost in the late 1980s, when Libya’s Gaddafy

donated four shipments of armaments such as surface-to-air missiles and Semtex high explosive. At Ballygawley village, the IRA detonated a Semtex bomb which killed eight soldiers in 1988. Home Secretary Douglas Hurd announced new restrictions to prevent broadcasters from transmitting voices of members of banned organisations or those that support them. Broadcasters got round this by lip-synching interviews using actors. One double of Gerry Adams made a small fortune during this time. The restrictions were useless and abandoned in 1994.

In any case, by the 1990s, the IRA were beginning to look to peaceful alternatives. Gerry Adams won the seat of West Belfast in 1983 and held it with an increased majority in 1987. In 1988 he held discussions with the SDLP’s John Hume which agreed on a common goal of ‘self determination’. Events elsewhere were also having an impact. The fall of the Berlin Wall gave the impression that Northern Ireland might be the last unsolved problem. While the IRA began to initiate talks, they also kept up the military pressure. During the Gulf War of 1991, they fired three mortars at

Downing Street, one of which landed in the backyard of Number Ten while a cabinet meeting was in progress. In 1992, they killed eight Protestant workmen in a landmine explosion.

But the bomb with the largest economic impact was the

Baltic exchange in the City of London. Three people were killed including a 15 year old schoolgirl. But the bomb caused £800 million of damage, eclipsing by £200 million the entire damage of the conflict to date since 1969. If repeated, it raised the prospect of devastating the British economy. The British made coded messages to the IRA that if they were prepared to call off the violence, anything might be possible. Through the early 1990s, there were talks and bombs in equal measure. In December 1993, Prime Minister John Major and Irish premier Albert Reynolds agreed the principles of what was called the Downing Street Declaration which insisted Britain had no interest in Northern Ireland but would only agree to a united Ireland if the majority of its citizens so wished.

In August 1994, the IRA announced a ceasefire. The Protestant paramilitaries followed suit. Talks got bogged down on the thorny issue of ‘

decommissioning’, the process of what would happen to IRA guns. But it was progress. 1995 was the first year in a quarter of a century where no members of the security forces were killed. In February 1996, the IRA bombed Canary Wharf in London killing two in protest at what it saw as British intransigence in the peace process. They would launch further assaults on the mainland in the run-up to the 1997 election including a threat that caused the cancellation of the Grand National at Aintree.

Tony Blair’s landslide win in that election gave the peace process new impetus. He offered talks once more and the IRA re-established a ceasefire in July 1997. At Easter 1998, Blair forced through the

Good Friday Agreement where all parties agreed to share power in a devolved assembly. Extremists within the IRA were unhappy and splintered off. One of the splinter groups called the “Real” IRA exploded a bomb in Omagh that caused the single largest casualty list of the entire conflict. 29 people died and 300 were injured. No one was charged for the bombing.

But Omagh did strengthen the resolve of the Good Friday Agreement participants. Prisoners from both sides were released. The decommissioning argument put the assembly on hold. Worse was to follow for the unionists when an independent commission on policing led by Chris Patten

recommended a new police authority to replace the sectarian RUC. Arguments raged back and forth until 9/11 threw a new spanner in the works. Nationalists were worried Bush would put the IRA back on his terror list. Meanwhile three IRA suspects were arrested in Colombia on charges of conspiring with rebel group FARC. The two events caused the Republican movement irreparable damage in the US. Despite this, they were now the leading Nationalist party in Northern Ireland after the June 2001 election. In October 2001, the IRA announced it had started the process to ‘put its weapons beyond commission’.

While the “farewell to arms” was not complete at the time of Taylor’s book, it was mostly complete by 2007. Last month saw a historic moment as bitter enemies Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness sat down next to each other to do business in the new Northern Ireland assembly. The hatred continues but the war was officially over.

An Irish company has bought out a former English court that has played an important and recurring role in Irish history. Galway-based Edward Holdings has purchased London’s former Bow Street Magistrates Court to turn it into a hotel. Over the years, the notorious former magistrates’ court has tried the Guildford Four, the Maguire Seven, Nazi propagandist William “Lord Haw-Haw” Joyce, Oscar Wilde and Roger Casement. While Wilde is probably the most famous Irish homosexual in history, Sir Roger Casement is surely the second. Casement was an Irish patriot, British diplomat,a poet and revolutionary. I've just finished reading two books where he featured prominently; Colm Toibin’s essays on homosexual artists “Love in a Dark Time” (Wilde also features) and “Roger Casement’s Diaries 1910: the Black and the White” edited by Roger Sawyer.

An Irish company has bought out a former English court that has played an important and recurring role in Irish history. Galway-based Edward Holdings has purchased London’s former Bow Street Magistrates Court to turn it into a hotel. Over the years, the notorious former magistrates’ court has tried the Guildford Four, the Maguire Seven, Nazi propagandist William “Lord Haw-Haw” Joyce, Oscar Wilde and Roger Casement. While Wilde is probably the most famous Irish homosexual in history, Sir Roger Casement is surely the second. Casement was an Irish patriot, British diplomat,a poet and revolutionary. I've just finished reading two books where he featured prominently; Colm Toibin’s essays on homosexual artists “Love in a Dark Time” (Wilde also features) and “Roger Casement’s Diaries 1910: the Black and the White” edited by Roger Sawyer. Casement returned to Africa in 1884 as an employee of the International Association a collection of committees dedicated to “civilising” the Congo, under the chairmanship of Belgium’s King Leopold. Casement returned from this assignment disillusioned with Leopold’s intentions for the Congo. The king was taking the profits from the rubber trade and turning the colony into his personal fiefdom. Casement joined the Consular service in 1892 aged 28. His first job was in the Oil Rivers Protectorate (now Nigeria). He was promoted to Consul in Lorenco Marques, capital of Portuguese Mozambique, in 1895.

Casement returned to Africa in 1884 as an employee of the International Association a collection of committees dedicated to “civilising” the Congo, under the chairmanship of Belgium’s King Leopold. Casement returned from this assignment disillusioned with Leopold’s intentions for the Congo. The king was taking the profits from the rubber trade and turning the colony into his personal fiefdom. Casement joined the Consular service in 1892 aged 28. His first job was in the Oil Rivers Protectorate (now Nigeria). He was promoted to Consul in Lorenco Marques, capital of Portuguese Mozambique, in 1895.