Last month marked the 40th anniversary of the historic 1967 referendum that allowed Australian aboriginals to be counted on the electoral roll. Before then, they weren't counted as people; they came under the Flora and Fauna Act. On 27 May 1967 for the first time in Australian history, black and white united for a common cause and 91 per cent of the white population voted in favour of changing the constitution. The referendum did not give Aboriginals voting rights; they had that already, though not many knew about it or exercised the privilege. What the referendum did do was to recognise Aboriginal rights to be counted in the census. It also allowed the commonwealth government to take responsibility for aboriginal affairs.

Last month marked the 40th anniversary of the historic 1967 referendum that allowed Australian aboriginals to be counted on the electoral roll. Before then, they weren't counted as people; they came under the Flora and Fauna Act. On 27 May 1967 for the first time in Australian history, black and white united for a common cause and 91 per cent of the white population voted in favour of changing the constitution. The referendum did not give Aboriginals voting rights; they had that already, though not many knew about it or exercised the privilege. What the referendum did do was to recognise Aboriginal rights to be counted in the census. It also allowed the commonwealth government to take responsibility for aboriginal affairs. To understand why Australia got to this point, it is necessary to return to its birth as a nation. The original constitution drafted for federation in 1901 had the belief that the continent’s original inhabitants would never become equal citizens. The common whitefella belief was aboriginals were headed for extinction. The blacks became non-citizens.

For that oversight to be corrected, the constitution needed to be changed in two places. Firstly Section 51 had to change. Clause 127 of Section 51 says the commonwealth has to right to pass laws for any race of people except aboriginals. Aboriginal policy was purely at a state level. The purpose of this clause was to allow the Commonwealth Government to make labour laws covering the Kanakas in Queensland. Later in the same clause it also stated aboriginals were not to be counted in the census. The effect of these clauses left the aborigines at the mercy of the state and with no statistics to condemn the situation.

This notion of "unperson" dates back to when the British first arrived in Australia and declared the continent terra nullius, a land without people. Each state set up aboriginal protection boards and aboriginals became wards of the state. They were forced to adopt Christian values designed to undermine their traditional societies. South Africa used the template provided by the protection board to set up their own apartheid regime. The protection boards had enormous powers. Aboriginals couldn’t move or marry without permission of the board. Mission managers doled off rations to those who live off the land. Wages were withheld and children removed from their parents. They were dispersed and dispossessed of their land.

In 1924, the first signs of aboriginal resistance to this oppressive regime emerged. Frederick Maynard led the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association which was the first organised aboriginal political group. It grew on the wharves of Sydney where aboriginals saw black men from other countries who shared their problems. A sense of common plight with American negroes saw aboriginals begin to define themselves as black Australians.

The question of aboriginal political rights first emerged in 1935 when Prime Minister Joe Lyons was petitioned for aboriginal representation in parliament by Aboriginal leader William Cooper. It was flatly rejected as constitutionally impossible. Black protesters mourned the passing parades as white Australia celebrated the 150th anniversary of the First Fleet landing in 1938. Maynard, Cooper and the Aborigines Progressive Association staged a Day of Mourning.

Cooper led the first mass strike of aboriginal people in 1939 when they walked off the land in protest at their conditions. But white interest was elsewhere. War was declared in faraway Europe and Prime Minister Robert Menzies sent off Australians to help their British brothers. When the war finally ended, the government introduced the Soldier Resettlement Scheme which gave land, often Aboriginal owned, to the returning troops.

White Australia grew in the 1950s and needed new immigrants to fill the jobs that were emerging in the booming economy. Under the paternal regime of minister of Territories Paul Hasluck, the policy towards Aboriginals was assimilation which insisted that they live more like white people. The policy echoed the assumptions of the writers of the 1901 constitution – that aboriginals would soon disappear.

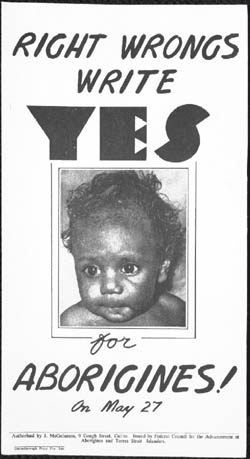

The promise of equality through assimilation was an illusion. By the 1960s aboriginals crowded into the cities where they formed ghettoes. Aboriginal support groups began to address the issues of day-to-day poverty in the city. In 1958 the first mainstream national indigenous body emerged, the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI). Its early leaders were Gordon Bryant, Sam Davis, Shirley Andrews, Jack and Jean Horner, and Faith Bandler. It demanded rights of association and the right to join a union. It rejected assimilation and demanded the right to their own culture. It also demanded citizenship rights.

FCAATSI began to organise nationwide. This was a problem in itself as Aboriginals needed permission to cross state boundaries. FCAATSI brought together a wide range of Aboriginal opinion of every political persuasion. It raised the profile of Aboriginal issues both nationally and, importantly, internationally. It worked on a growing reputation that Australia was gaining of having a racially divisive government. Menzies was stunned and stung when Khrushchev accused Australia of a policy of extermination at the UN. The civil rights movement in the US also provided impetus. In 1965 Charles Perkins organised a freedom ride following the US example. For the first time ever, Aboriginal issues had captured the attention of the media. The ride went from Sydney to the outback town of Walgett where a protest was planned against segregation.

In 1966, the Gurindji people went on strike at Wave Hill in NT in an attempt to win wage parity with the white workers. FCAATSI supported the strike and criticised the court decision for a two-year wait to get equal pay. In 1958, television footage of ragged Aboriginals at Warburton, WA shocked the nation. The Warburton people lived at Maralinga, SA until the government took the land for A-bomb tests. They then shunted the Aboriginals across the border and abandoned them to their fate in a harsh land they were not familiar with.

The grainy TV footage galvanised the interest of a white Australian human rights activist Jessie Street. Her intervention would prove crucial. Street wanted to bring the issue to a sub-committee of the UN. She knew that this was the time to push for a change to the constitution. She saw the constitution as the base for Australia’s racism. Initially she was unsuccessful in lobbying Hasluck for change. But she did succeed in convincing FCAATSI leaders Faith Bandler and the Horners that constitutional change was the key. FCAATSI drew up a petition to change section 51 clause 127.

The petition also called for end to limitation of aboriginal rights, equal pay, the right of access to traditional lands and an end to anything that prevented Aboriginals from becoming equal citizens. They gained 100,000 signatures and presented it to the House of Parliament ten years in a row. They also wrote letters to influential people including MPs, mayors, councillors and business leaders. They handed out leaflets and held protests.

Some FCAATSI members were worried the constitutional crusade distracted the movement from more substantial issues. Living conditions, education and employment were immediate needs many thought might not be solved by a referendum. But Menzies eventually agreed to meet a FCAATSI delegation in 1963. He was sympathetic but unconvinced that a constitutional change was required.

Menzies retired in 1966 and suddenly FCAATSI had to deal with Harold Holt. Holt was anxious to step out of Menzies' shadow and he was the one to give the nod to the referendum. He agreed to the referendum in 1967 because he wanted to change another unrelated aspect of the constitution, section 24, known as the Nexus Question. The first question on the referendum on the ballot would be the Nexus Question which would allow politicians to increase their numbers in parliament. The government hoped that the popular Aboriginal change would get the Nexus Question over the line.

The referendum got overwhelming support from the countries intellectuals and bipartisan support from the political parties. On 27 May, 1967 the referendum occurred at the end of a ten year campaign. Worried by the Australian tendency to defeat constitutional change (29 had been rejected and only 5 narrowly accepted), FCAATSI fretted over the possible verdict. They need not have worried. The result was overwhelming. 90.77 per cent voted in favour of the Aboriginal amendments and it was carried in every state. Holt didn't get what he wanted - the Nexus Question was defeated 40-60. But it was a resounding triumph for the Aboriginal cause.

Elated Aboriginals believed the future was theirs but that promised land never arrived. Aboriginal policies on land rights, the National Aboriginal Conference (1971), hopes of a treaty and ATSIC (the Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islanders Commission) were all failures. By 1988 and the bi-centennial of Australia’s colonial beginning, Aboriginals marked another day of mourning. The 1967 referendum had not changed their basic living conditions.

Today Aborigines wonder what it means to be an Australian citizen. John Howard makes no distinction between those who are indigenous, those who are British or Irish and those who arrived after the war, “each no better than the other”. Howard proclaims the Federation goal of “one people, one destiny” without taking into account that Federation discriminated against Aborigines. Howard refuses to apologise for the past and promotes a policy of “practical reconciliation”.

But how practical has it been? The aboriginal prisoner population has doubled since 1988. Indigenous men have a life expectancy of 59 years compared to 77 years for the rest of the community. For females it is 65 compared to 82 years. The average household income for indigenous people is $364 a week. The unemployment rate among Aboriginals is almost 50 per cent. The Aboriginal retention rate for Year 12 students is 38 per cent compared to 73 per cent for non-Aboriginals.

But how practical has it been? The aboriginal prisoner population has doubled since 1988. Indigenous men have a life expectancy of 59 years compared to 77 years for the rest of the community. For females it is 65 compared to 82 years. The average household income for indigenous people is $364 a week. The unemployment rate among Aboriginals is almost 50 per cent. The Aboriginal retention rate for Year 12 students is 38 per cent compared to 73 per cent for non-Aboriginals. Nonetheless, the referendum is worth celebrating. It remains the most popularly supported constitutional change in Australia’s history. As the National Indigenous Times puts it, “it is an important reminder that it is possible to capture the hearts and minds of other Australians. That once in while, the mood is right and Australians understand that the place of Indigenous people in Australian society is an important part of their own story”.

1 comment:

it is really sad that a human population is treated in this manner in a country as civilised as Australia. Where is human right? Where is the geneva convention? Where is the united nation? Where in deed is humanity? Belief it or not, we will all answer for this atrocity. My heart goes to the aborigines. It is God that created you and it is no fault of yours that the world has turned a blind eye to your situation. May God protect and make you and make you human again.

Ahmed in Nigeria west africa.

Post a Comment