Islam is the fastest growing religion in the world. There are over 1.25 billion adherents - one in five of the world’s population is Muslim. It is also the most misunderstood religion in the world and is at the forefront of an apparent conflict with Western values. Yet Islam has interacted with the western world for more than 1,400 years. Some of today’s areas of conflict are rooted in events that took place hundreds of years ago. An examination of that history is useful in understanding present events.

In the centre of Mecca lies an old square building known as the Kaaba, It is Islam’s holiest site. According to Islamic tradition, the Kaaba was built by biblical Adam as a place of worship. Abraham then built a second building on the site after the first was destroyed. It has been renovated many times since. In the wall of the Kaaba lies a sacred black stone which experts believe to be a meteorite. About 1,400 years ago storms had damaged the Kaaba. A dispute arose between the four tribes of Mecca as to who would have the honour of replacing the black stone. A local trader solved the dispute by placing the stone in a cloth which was lifted by members of all four tribes. That trader’s name was Muhammad.

Muhammad ibn Abdullah was a native of Mecca, born there in 570 CE. Muhammad’s father died before he was born and his mother died shortly afterwards. Muhammad was raised by an uncle and helped the family by tending sheep. When he was 25 he travelled to Syria to sell the goods of a rich businesswoman named Khadija. Muhammad impressed her by the profit he made and she proposed to him. They had four daughters who lived and two sons who died young.

While Muhammad quickly gained the reputation of a wise and honest man, the same could not be said of Mecca. The traditional Arab care of the disadvantaged was waning in what was then a rich polytheistic international trading post. Women were brutally oppressed and some parents killed their daughters for fear of bring bad luck. Meanwhile Muhammad was about to receive an epiphany. According to the Koran, Muhammad was transported one night to Jerusalem where he ascended into Heaven and spoke to Abraham, Moses and Jesus. This became known as Muhammad’s Night Journey and it affirmed his belief that God (Allah) required him to preach for a monotheistic faith.

Muhammad preached submission to the will of Allah and the new religion became known as Islam from the Arabic verb ‘aslama’ meaning surrender or submission. He began publicly preaching in 612 CE and developed the Five Pillars of Islam, the five required duties of all Muslims. These were: a profession of faith in one God (Allah), prayer at five times each day, alms to the poor (zakat), fasting during the holy month of Ramadan (the ninth month of the Islamic calendar) until the festival of Eid al-Fitr (the breaking of the feast) and finally the Haj – at least one pilgrimage to Mecca during a Muslim’s lifetime.

The new religion appealed to the poor, the oppressed, and the women. The rich and powerful leaders of Mecca were suspicious of Muhammad’s message of social justice. His monotheism also threatened the tourist trade of idol worshippers to the Kaaba. So they passed laws anti-Muslim laws that banned trade and social relations with Muslims. Muhammad and his followers were forced to abandon their native city ahead of a plot to assassinate him. This flight known as the “hijra” took place in 622. They went to Yathrib about 400kms north where they were warmly greeted after they helped tribal leaders sort out ancient differences. The city was quickly Islamised and its name was changed to Medina “the prophet’s city”.

The base of Islamic life is the “ummah” or Muslim community. The ummah is a tighter social bond than a family or a tribe. Ummah members must protect and defend each other at all costs. A key to the ummah’s success was that it applied to the entire community – not just its Muslim members. This concept replaced the traditional Arab notion of obligation based on blood relationships. Acceptance of this new social ideal was a key to Medina’s success.

After several years of war with Mecca, Medina finally triumphed in 630 when Muhammad led a 10,000 strong army to the city of his birth. Mecca surrendered without a fight. After the conquest many people living there decided to become Muslims. Muhammad and his followers then began to quickly spread the new message throughout the Arabian peninsula. By the time of Muhammad’s death two years later in 632, most of Arabia was united and Muslim.

The biggest question after Muhammad’s death was who would succeed him as leader or caliph (from the Arabic word for deputy or successor) of the ummah? Some wanted Ali ibn Ali Talib, Muhammad’s son-in-law and closest living male relative, to succeed himself. However after much discussion, a man named Abu Bakr was chosen as the first caliph. He was one of Islam’s earliest converts, a close friend of Muhammad and the father of Muhammad’s second wife. Bakr had to deal immediately with the Apostasy Wars against Arab tribes that believed their responsibilities to pay zakat ended when Muhammad died. The rebellions were quickly suppressed. By the time Bakr died after another two years in 634, the Islamic kingdom was twice as large again.

The second caliph Umar al-Khattab reigned for ten years during which Islam spread rapidly through the Middle East. Muslim armies conquered Syria and Egypt from the Byzantine Empire and also took Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) from the Persian empire. Non-Muslims (dhimmi) in these areas who did not wish to convert were forced to pay a protection tax called jizya which was equivalent to the Muslim zakat. These taxes were an important source of funds for the expanding empire. After al-Khattab was murdered by a Persian slave, the third caliph Uthman ibn Affan reigned for another 12 years. He was assassinated by followers of the still disgruntled Ali Talib who was proclaimed the fourth caliph.

Ali’s appointment caused a civil war and a major schism in Islam. He was assassinated by his enemies in 658 and his murder brought to end what was known as the era of the “rightly guided caliphs”. Ali’s supporters accepted his son as caliph however the majority rallied behind Ali’s opponent Abi Sufyan, a kinsman of Uthman, the third caliph. This group of Muslims became known as the Sunni (“the path”) which comes from the example of the “Sunna”, Muhammad. The followers of Ali and his son became known as Shiites from the Arabic “Shiat Ali” (party of Ali). Today more than 80 per cent of Muslims are Sunnis and a further 15 per cent are Shiites.

Despite decades of turmoil, the growth of Islam continued in the early years. By 718 Muslim armies ruled North Africa, the Middle East, Persia, Afghanistan and Iberia. A group known as the Abbasids gained control in 750 and created a new dynasty that would rule for several centuries from their new capital in Baghdad. A rival Umayyad dynasty ruled the Moorish state of Andalusia in Southern Spain which became the most enlightened European civilisation of the eight and ninth century. Cordoba was a famed and tolerant city of learning while most of Europe was plunged into the Dark Ages. Muslims advanced ancient knowledge in geography, astronomy, mathematics, science, medicine and philosophy.

Despite the Arab enlightenment, the Abbasids found it difficult to manage their unwieldy empire. Independent Muslim kingdoms emerged to claim local lands in India, Iran, Arabia and Turkey. The Moors were finally expelled from Granada in 1492, the year of Columbus’s first voyage to the Americas. But it was an earlier series of events starting in the 11th century that was to define Christendom’s complex relationship with Islam: the Crusades.

In 1095 Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Kemnenos asked the pope for help in fighting Turkish Muslims. The pope saw this as an opportunity to increase his power in the orthodox Eastern empire and called on European Christians to fight a holy war or crusade against the Muslims. A 60,000 strong army from England, France and Germany was charged to eliminate the Turkish threat from Byzantine and to also capture the holy city of Jerusalem. The crusading armies robbed and pillaged from all countries along their route, massacring German Jews and fighting Hungarian peasants. Although they failed in their ill-equipped mission, a second group of 100,000 captured Nicea, the Seljuk Turk capital and sacked the walled city of Jerusalem in 1099.

The Crusaders established four small Christian kingdoms in the areas of modern-day Israel, Jordan and Lebanon. They were surrounded by hostile Muslims whose lands they had taken. After Muslim forces retook Edessa in Syria in 1144, Bernard of Clairvaux called for a Second Crusade. French King Louis led his forces into the Middle East where they were routed leaving the Crusader states more vulnerable than before. The great Kurdish Muslim leader Saladin began to recapture cities including Jerusalem and a Third Crusade led by England’s King Richard was sent to stop him. After initial successes the two armies were locked in stalemate. The two sides negotiated a truce that kept Jerusalem in Saladin’s hands. Several more crusades were launched, each weaker than the last. Although Frederick II’s sixth Crusade temporary recaptured Jerusalem, the Crusader states finally collapsed in 1291 after 200 tragic and wasteful years.

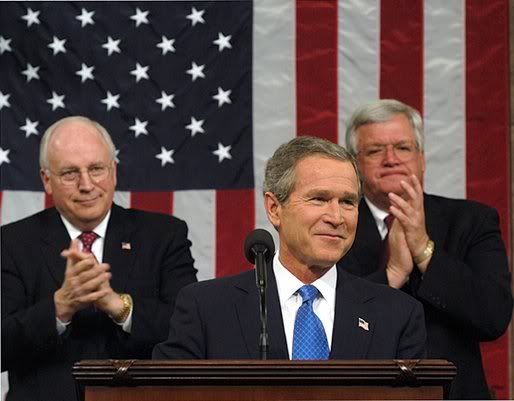

While the crusade is still a positive concept in modern Christian countries, it is a pejorative word in Muslim countries allied to invasion, aggression and brutality. George W Bush’s description of the “war on terror” as a crusade offended many Muslims because of these historical connotations. In the Crusades, Christians fought a Holy War and the Muslims responded with “jihad”. The word jihad means struggle and in law means a struggle to maintain the balance of justice by an equitable distribution of rights and duties.

The next danger to Muslim hegemony came from the East. The Mongols began invading Muslim countries in 1220. Genghis Khan led a worldwide empire which obliterated cities, burned libraries and killed thousands. But the Muslims had their own cultural victories and by 1313 the Mongols made Islam their official religion. By now Islam’s reach was prodigious stretching through India, China, Malaysia and Indonesia in the East and the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa in the west. This is roughly analogous to Islam’s current sphere of influence.

A new Muslim empire grew in the early 14th century. Under the leadership of Osman I, the Ottoman Turks removed the Seljuks from power and began to grow in strength. They chipped away at the Byzantine Empire and finally took Constantinople in 1453. They renamed the city Istanbul meaning “city of Islam”. The fall of Constantinople caused a mass exodus of scholars and artists to Italy and would be a direct cause of the Italian Renaissance.

The Ottomans would prove tolerant rulers allowing Christians and Jews to live in their empire. They were great lawmakers and build complex legal institutions and tax structures. The empire flourished due to its good governance aided by a well-trained army and an effective network of spies. The Ottoman sultan was not only the head of the Government; he was also the caliph and therefore religious leader of Islam. The greatest of these sultans was Suleiman who ruled between 1520 and 1566. He was a poet and lawmaker and scholarship and fine architecture flourished under his rule. In 1529 his armies arrived at the gates of Vienna but were repulsed. Nonetheless Austria and Russia would fear the Ottoman Empire for the next two centuries.

The beginning of the Ottoman downfall came with the rise of European colonialism. Until the 16th century, the Ottomans controlled the overland routes to Asia and Africa and they charged high taxes to travelling merchants. Portuguese explorers led the way in discovering new sea routes to Africa and India while first Spanish and then British sailors led the way across the Atlantic. The Europeans quickly dominated the culture of the new hemisphere and then began to look east for new spoils.

They forced weaker Muslim potentates into preferential trade deals which began to shift the balance of power. When the Industrial Revolution started in the 18th century, Europe had the advantage it needed to dominate international commerce. The Portuguese arrived first capturing the seaports before they passed the baton onto the commercial seafaring nations of Britain and the Netherlands. In 1765 the British East India Company forced the weak Islamic Moghul emperor of India to yield his authority. The Dutch conquered the East Indies while the French took large swathes of north and west Africa.

As Muslims and Westerners came into closer contact, Islamic society was forced to adapt. Some Muslims wanted the best of both worlds by adopting Western technology while remaining faithful to their own heritage. Others tried to merge Islamic ideas with Communism or harness a growing nationalism. The idea of a nation state was imported from Europe and was taken up by Arabs who wanted freedom from the Ottomans. The empire became embroiled in the first world war and British envoys such as T.E. Lawrence went to the peninsula to encourage an Arab rebellion. In 1916 Hussein bin Ali fought with the British to take Damascus.

But Britain was two-timing the Arabs. While encouraging Ali’s revolt, they also sat down with the French to carve out the Sykes-Picot agreement which divided Ottoman territories between them after the war. Another complication was the Balfour Declaration by the Britain’s foreign secretary which supported the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. After the war, the British and French divided the territories into new mandates such as Transjordan, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq, which Palestine aside, all achieved independence after the Second World War.

The end of that war also saw independence to India. However tensions between India’s Hindu majority and its Muslim minority led Britain to divide the colony into India and Pakistan. Muslim Kashmir remained in Indian hands and 250,000 people were killed in the violence that followed. Another 12 million people were made refugees by the partition. Pakistan’s unwieldy nature, two sides 1,800 kms apart, could not be sustained and the East broke away as Bangladesh after another war in 1971.

While Europe was intimately involved with Islam, the US had so far kept at arms length. However its influence in Muslim countries grew after the break-up of the British and French empires in the 1940s and 50s. The US was initially widely admired in Muslim countries because it didn’t appear to practice the suppression of nationalist and religious movements so beloved of the Europeans. However as the Cold War grew, the US became more active in Muslim countries, and its CIA active engineered Suharto’s military coup in 1965, Indonesia’s Year of Living Dangerously.

But it was oil that would define the US’s relationship with the Arab world. In the 1950s, the US enlisted the support of oil-rich Arab states ruling families in exchange for financial and military assistance. They signed a mutual defence pact with Saudi Arabia in 1951. Two years later, the CIA launched a coup in Iran to overthrow a reform-minded Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh who threatened to nationalise the country’s oil industry. He was replaced by Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi who supported Iran’s westernisation until he was overthrown during the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

Also in 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. The new Communist regime did not permit Muslims to freely practice their religion. Resistance fighters known as mujahideen from all around the Islamic world took up the fight against the Soviets. They were supported by the CIA who provided $3 billion in weapons and military training. One of the lessons the mujahideen learned from the US was the concept of “strategic sabotage”, a lesson that former mujahideen Osama bin Laden would apply with devastating effect against the US in 2001. After a ten year war in Afghanistan, the Soviets withdrew. This defeat contributed greatly to the break-up of the USSR in 1991 and the end of the Cold War. The US also pulled its resources out of Afghanistan and left a power vacuum behind. Out of the different groups of mujahideen emerged a group called the Taliban which established a religious government in Kabul in 1996.

Meanwhile the US continued to invest in its long partnership with Israel. Although the US was the first country to recognise Israel’s independence in 1948, the two countries did not become close until after the Suez Crisis. The US supported Nasser in that crisis but Eisenhower’s fear of Egypt’s close ties with the USSR led to a new role for Israel as a bulwark against the spread of Communism. Israel used mostly French weapons up to the 1967 Six Day War but after the Israeli victory, the US became its leading arms supplier. The capture of East Jerusalem in that war and the loss of Islam’s second holiest shrine deeply offended Muslims throughout the world. 40 years later, it remains contested territory with Israel refusing to compromise on its return to a Palestinian state. The other vexed issue is the issue of land grants to Jewish settlers in annexed territories on land formerly owned by over a half million Palestinian Arabs.

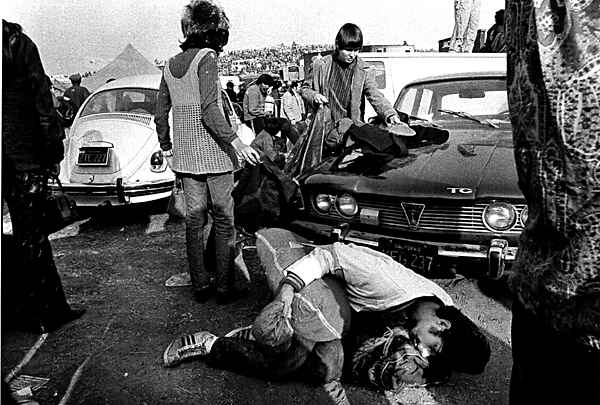

After the 1967 war Palestinian opposition groups became more radical. The PLO began terrorist attacks against Israeli targets, most notably at the 1972 Munich Olympics. Israel retaliated by bombing PLO bases and assassinating their leaders. In 1982 Israel, supported by the US, invaded southern Lebanon to drive out the PLO. Israel would occupy a “buffer zone” until 2000. Meanwhile the US attempted to keep the peace. Kissinger’s “shuttle diplomacy” ultimately led to a thawing of relationships with Egypt and a historic peace treaty with Israel. But the rest of the Arab world were outraged by Egypt’s treachery and a Muslim extremist assassinated President Sadat in 1981. Nonetheless the treaty called for Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai and the Palestinian enclaves in Gaza and the West Bank. Israel withdrew from the Sinai but reneged on the vague wording about the Palestinian territories.

Angered by continued delays and crushing poverty, the Palestinians launched a series of protests in 1987 that became known as the Intifada (Arabic “shaking off”). Israel met the protests with force and over a thousand Palestinians died as the violence continued over the next six years. Bill Clinton negotiated a new agreement in 1993 that led to the formation of a provisional government known as the Palestinian Authority a year later. But yet again one of the architects of a peace agreement was assassinated by an extremist. This time it was Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rubin who was shot by a Jewish militant in 1995. Rabin’s hawkish replacement Benjamin Netanyahu antagonised Muslims by authorising an archaeological dig under Jerusalem’s al-Aqsa mosque.

The peace process dragged on through the 1990s with no sign of a lasting settlement. Positions hardened. In 2000 the Palestinians launched a second intifada which included suicide attacks and the Israelis responded by military force and martial law. The West blamed PLO chairman Arafat for not being committed to peace while the Muslim world believed that Israel could do what they pleased while it was supported by the US. Although some progress has since been made in Palestinian statehood, albeit complicated by the Hamas takeover of Gaza, the issue of Israel remains the fulcrum of disagreements between Muslims and the West.

But the Palestinian question is beginning to be overtaken by events to the east. In 1979 a popular revolution overthrew the US-backed Shah of Iran. The new government was an Islamic theocracy based on Shiite principles. Iran broke off diplomatic relations with the US and began to eliminate Western influences from Iranian society. A year later its neighbour Iraq seized on the perceived weakness of the new regime to invade Iran. In the gruelling eight year war that followed, the officially neutral US supported Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein with weapons and aid. The war ended in stalemate and sent Iraq broke.

Saudi Arabia and Kuwait rejected Saddam’s call to forgive his debts. Saddam decided to invade Kuwait and seize its massive oil fields with 20 per cent of the world’s known reserves. The invasion rattled Saudi Arabia. The ruling Al Saud family feared their kingdom might be next to fall to Saddam’s armies. The Saudis requested help and the US sent in thousands of troops to support Operation Desert Shield. Saddam defied UN demands to withdraw. Finally a coalition of 30 countries (many of them Muslim) attacked starting the 1991 Gulf War. This quick and brutal war was hopelessly one-sided. 400 Iraqi soldiers died (150,000 in all) for every coalition casualty (just 370 dead).

Iraq was plunged in turmoil after the war. Minority groups rebelled against Saddam expecting outside support. But the US armies did not intervene and the Iraqi army put down the revolts. The UN Security Council set a resolution for the end of the war. Iraq was to renounce its claim to Kuwait and destroy its weapons of mass destruction. The US maintained economic sanctions throughout the 1990s as it sought Iraqi compliance. The sanctions hurt the poor but did little to upset Saddam. Finally the 9/11 attacks gave the new Bush administration the excuse it needed to effect regime change. The eventually war in 2003 and Saddam’s overthrow have opened up a new Pandora’s Box whose contents have not yet entirely spilled out.

But the Middle East is not the only place where the West meets Islam. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 saw many new countries emerge in Central Asia. Many of these nations - Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan – have majority Muslim populations. All are struggling to establish political, economic and social stability. Azerbaijan has lost control of a fifth of its territory to Christian neighbour Armenia in a border dispute. Another Muslim enclave Chechnya has twice gone to war with Russia in a so far vain attempt to win independence from Moscow. Bosnia and Herzegovina has also struggled with religious tensions and ethnic cleansing after a bitter war of independence from Serb-dominated Yugoslavia.

In all of these troubled regions, some Muslims have taken extremist positions to defend their rights. Those that want to use a strict interpretation of Islamic (Sharia) law as the basis for the government and society are known as fundamentalists in West. However contemporary scholars prefer the term Islamists as the term fundamentalism was invented to describe conservative Christian belief. Islamists usually have a commitment to help poorer members of society and also reject some aspects of Western culture.

Sometimes more extreme Islamist groups interpret the concept of jihad (a complex term meaning struggle against cultural and social corruption) to justify acts of violence. Because these groups are small and have limited resources, their most effective weapon is terrorism. Terrorism is violence carried out for political purposes. While most in the West equate “terrorist” with “Muslim”, the idea has been around for centuries and used by various minority groups to achieve their aims. Meanwhile the majority of Muslims condemn terrorism and scholars say it has no place in Islam.

However Islamist political parties are on the rise. The Muslim Brotherhood has renounced terrorism in Egypt and Jordan and have joined the political process with some success. In secular Turkey, the moderate Islamist Justice and Progress Party (AKP) gained power in 2002. However when the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) won power in Algeria in 1992 it was banned by the military and led to a vicious civil war. Other Islamist organisations have combined social activism with terrorist activities. Hezbollah (“Party of God”) was founded in 1982 to combat the Israel occupation of Lebanon. Hezbollah have engaged in with military actions against Israeli and US targets. Their goal is to found a fundamentalist state along Iranian lines. Hamas have similar goals in Gaza.

In Indonesia Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) have been responsible for a series of bombings including the two attacks on Bali. Their goals is to set up a Muslim super-state encompassing Malaysia, Indonesia and southern Philippines. JI have links to the most infamous Islamist group of all – al Qaeda. Bin Laden’s group has carried out massive attacks including 9/11, the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania and the USS Cole bombing.

However it is important to realise that the reason groups like al Qaeda resort to terrorism is that they have very little real power. Terrorists are afraid that the powerful will never address their concerns unless they can get their attention by dramatic acts. It is important that the West does not demonise Islam as a whole for the actions of its radical elements. The Islamic World itself is as varied as the Western world. But cultural difference doesn’t mean Muslims and Westerners cannot co-exist peacefully. The west needs to be aware of the political, economic and social circumstances that hinder Muslim development. The west cannot solve these problems but can help. But they must respect Muslim ways of thinking and allow them to devise solutions to their problems that conform to the religious beliefs of their people.

note: this essay is based on the ideas in Evelyn Sears's book

Muslim and the West.

Thousands celebrated today in the Malaysian capital, Kuala Lumpur, as the country marks 50 years of nationhood. Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi used an anniversary speech to urge people to unify as a nation. "We must ensure that no region or community is left behind," he said. "We will hold true to the concept of justice and fairness for all citizens." The celebrations mask a debate which is growing about what it means to be Malaysian in the ethnically diverse nation.

Thousands celebrated today in the Malaysian capital, Kuala Lumpur, as the country marks 50 years of nationhood. Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi used an anniversary speech to urge people to unify as a nation. "We must ensure that no region or community is left behind," he said. "We will hold true to the concept of justice and fairness for all citizens." The celebrations mask a debate which is growing about what it means to be Malaysian in the ethnically diverse nation.  The legacy of bumiputra affects Malaysia today. The government does not impose any restrictions on minority races, who are free to practice their own culture, religion and education. Nevertheless, the races that make up its multicultural population remain poles apart. They have separate friends and lead separate social lives. Most Chinese and Indians send their children to Mandarin and Tamil language schools while the Malays attend national institutions. Former deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim now proposes to reform the political landscape to promote national harmony. "We need to appeal to the Malays, Chinese and the Indians and the rest that we need to go beyond race-based politics,” he said. “If you continue to harp and support this racial equation, you will never be able to overcome racial divisions”.

The legacy of bumiputra affects Malaysia today. The government does not impose any restrictions on minority races, who are free to practice their own culture, religion and education. Nevertheless, the races that make up its multicultural population remain poles apart. They have separate friends and lead separate social lives. Most Chinese and Indians send their children to Mandarin and Tamil language schools while the Malays attend national institutions. Former deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim now proposes to reform the political landscape to promote national harmony. "We need to appeal to the Malays, Chinese and the Indians and the rest that we need to go beyond race-based politics,” he said. “If you continue to harp and support this racial equation, you will never be able to overcome racial divisions”.