Monday, July 16, 2007

Woolly Days offline

Due to a family emergency in Ireland, Woolly Days will be off the air until further notice.

Sunday, July 15, 2007

Fuck the Children: English language taboos in 2007

If you can’t say fuck, you can’t say “fuck the government” – Lenny Bruce

The word "fuck" continues to have the power to create great fear. In this week alone, the word has made it into the news in many unrelated ways. The Canadian band Nickelback caused uproar in the Prince Edward Island city of Charlottetown when they swore at the city's "family-friendly" Festival of Lights. They also threw beer into a section of Confederation Landing Park that wasn't designated for alcohol. Local councillor Cecil Villard suggested the band play a “free family-friendly concert” to make up for their bad behaviour while Mayor Clifford Lee told the local Guardian newspaper “people were really, really disappointed and really upset."

In Britain a more well-known Guardian discussed the equally upsetting Diaries of Alastair Campbell released last week. Tony Blair’s media manager, a man in his own Lear-like words “more spinned against than spinning,” admitted in the diaries to being a misanthrope. When his cabinet colleague Peter Mandelson asked Campbell "Do you like anyone?" he responded he liked his children and also his partner Fiona but only when she's not disagreeing with him. He added “the rest can fuck off”. Campbell justified his part in Britain’s decision to back the US invasion of Iraq but was betrayed by others such as the BBC, Geoff Hoon, Tony Blair because "they all fuck up." Number 10 Downing St, according to Campbell was Peyton Fucking Place.

A more whimsical use of "fuck" was in Dorian Lynskey's article in the same newspaper discussed great swearing songs and came up with a top ten that has Rage Against the Machine’s “Killing in the Name Of” at number one. John Cooper Clarke’s Evidently Chickentown is at number nine even though he bowdlerised the poem on the recording by substituting a “bloody” for every “fucking”. Although the Guardian has a policy of spelling out fuck, even it was coy about what it called “the most powerful expletive of all - the one that rhymes with James Blunt”.

Even with James Blunt at his service, British journalist Ed Conway is unhappy about the staidness of the current cache of curses and is launching a Facebook campaign to find fresh swearwords for the 21st century. Conway believes words like fuck and cunt have been neutered by overuse. He suggests we try the likes of spaff, pok, gash, gosling, ragnarok, shagsak, bacardigan or melted welly. One of Conway’s respondents wrote back: “Whatever we come up with, at least it’ll be better than Battlestar Galactica’s ‘frack.’” Sounds like a load of melted welly to me.

Even with James Blunt at his service, British journalist Ed Conway is unhappy about the staidness of the current cache of curses and is launching a Facebook campaign to find fresh swearwords for the 21st century. Conway believes words like fuck and cunt have been neutered by overuse. He suggests we try the likes of spaff, pok, gash, gosling, ragnarok, shagsak, bacardigan or melted welly. One of Conway’s respondents wrote back: “Whatever we come up with, at least it’ll be better than Battlestar Galactica’s ‘frack.’” Sounds like a load of melted welly to me.

Moving forward to the brave new world of 21st century swearing, Punknews.org’s GlassPipeMurder reviewed “Use Your Delusion” a new album by Shit Piss Fuck. SPF is, according to Punknews' admiring reporter, “the most attention-whoring name I’ve ever heard”. Shit Piss Fuck play a kind of “squatter punk / crustified crackrocksteady” music. Their song “Fortified wine” begins:

“If you live in North Carolina or South Dakota or Oklahoma

Then you already know the fucking truth”.

It's unlikely Rod Stewart will be listening to Shit Piss Fuck any time soon. Stewart has just admitted he was “shaken” by the use of foul words used at the Live Earth concerts, and he promised to his own audience three days later to keep his gig free of foul language. Stewart made a pledge to his audience in Coventry last week. "If you hear me swear on stage I'll give you all a tenner” he said. The canny Scotsman Stewart can given himself a monetary incentive for keeping a civil tongue.

The words that shook Stewart in the first place were uttered by comedian Chris Rock. At the gig Rock swore “I’m just jokin’, motherfuckers. Shit” while introducing the Red Hot Chili Peppers at Live Earth. He was cut off by the BBC and its TV presenters Jonathan Ross and Graham Norton apologised to viewers saying that all artists had been warned not to use “bad language during the show”. Showing the priorities of Web 2.0, the Youtube video showing Rock swearing was removed not due to its language but because of a copyright claim.

In the morally uptight world of US free-to-air television, it is a violation of federal law to broadcast indecent or profane programming during certain hours. The law is “vigorously enforced” by the Federal Communications Commission. In 2004, the FCC took action in 12 cases, involving hundreds of thousands of complaints and dished out $8 million in penalties. Under President Bush, the FCC toughened its enforcement penalties by issuing monetary penalties based on each indecent utterance rather than a single penalty for the entire broadcast.

Earlier last month, the 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals made a landmark decision rejecting 2-1 the FCC’s fines against networks in cases that involved "fleeting expletives" such as those Cher and Nicole Ritchie issued during the 2002 and 2003 Billboard Music Awards. The court noted President Bush himself has been caught uttering “shit” on television, meaning the FCC was acting arbitrarily.

Tim Winter is president of the Parents Television Council, an extremist advocacy group that has argued for stricter FCC regulation. Last week he supported Republican presidential hopeful Senator Sam Brownback (R-Kan) who planned to introduce an amendment to strengthen the enforcement of broadcast decency laws to protect children from violence and sexual material on television. The bill would strengthen the FCC’s ability to act against networks using “indecent material”. Winter said they hoped the Senate would affirm the FCC's authority to enforce the broadcast decency laws "rather than letting two judges in New York override strong public opinion”.

Winter, like many conservatives, used protection of children as the overriding reason for restrictive laws. The PTC’s slogan is instructive: "because our children are watching”. It is time to remind Winter and co of a fundamental truth: It's not all about children. Maybe he should listen to "seven-swear-words" comedian George Carlin who said:

Winter, like many conservatives, used protection of children as the overriding reason for restrictive laws. The PTC’s slogan is instructive: "because our children are watching”. It is time to remind Winter and co of a fundamental truth: It's not all about children. Maybe he should listen to "seven-swear-words" comedian George Carlin who said:

Carlin finished his plea with a question: “You want to know how to help your kids?" His answer: “Leave them the fuck alone”.

The word "fuck" continues to have the power to create great fear. In this week alone, the word has made it into the news in many unrelated ways. The Canadian band Nickelback caused uproar in the Prince Edward Island city of Charlottetown when they swore at the city's "family-friendly" Festival of Lights. They also threw beer into a section of Confederation Landing Park that wasn't designated for alcohol. Local councillor Cecil Villard suggested the band play a “free family-friendly concert” to make up for their bad behaviour while Mayor Clifford Lee told the local Guardian newspaper “people were really, really disappointed and really upset."

In Britain a more well-known Guardian discussed the equally upsetting Diaries of Alastair Campbell released last week. Tony Blair’s media manager, a man in his own Lear-like words “more spinned against than spinning,” admitted in the diaries to being a misanthrope. When his cabinet colleague Peter Mandelson asked Campbell "Do you like anyone?" he responded he liked his children and also his partner Fiona but only when she's not disagreeing with him. He added “the rest can fuck off”. Campbell justified his part in Britain’s decision to back the US invasion of Iraq but was betrayed by others such as the BBC, Geoff Hoon, Tony Blair because "they all fuck up." Number 10 Downing St, according to Campbell was Peyton Fucking Place.

A more whimsical use of "fuck" was in Dorian Lynskey's article in the same newspaper discussed great swearing songs and came up with a top ten that has Rage Against the Machine’s “Killing in the Name Of” at number one. John Cooper Clarke’s Evidently Chickentown is at number nine even though he bowdlerised the poem on the recording by substituting a “bloody” for every “fucking”. Although the Guardian has a policy of spelling out fuck, even it was coy about what it called “the most powerful expletive of all - the one that rhymes with James Blunt”.

Even with James Blunt at his service, British journalist Ed Conway is unhappy about the staidness of the current cache of curses and is launching a Facebook campaign to find fresh swearwords for the 21st century. Conway believes words like fuck and cunt have been neutered by overuse. He suggests we try the likes of spaff, pok, gash, gosling, ragnarok, shagsak, bacardigan or melted welly. One of Conway’s respondents wrote back: “Whatever we come up with, at least it’ll be better than Battlestar Galactica’s ‘frack.’” Sounds like a load of melted welly to me.

Even with James Blunt at his service, British journalist Ed Conway is unhappy about the staidness of the current cache of curses and is launching a Facebook campaign to find fresh swearwords for the 21st century. Conway believes words like fuck and cunt have been neutered by overuse. He suggests we try the likes of spaff, pok, gash, gosling, ragnarok, shagsak, bacardigan or melted welly. One of Conway’s respondents wrote back: “Whatever we come up with, at least it’ll be better than Battlestar Galactica’s ‘frack.’” Sounds like a load of melted welly to me.Moving forward to the brave new world of 21st century swearing, Punknews.org’s GlassPipeMurder reviewed “Use Your Delusion” a new album by Shit Piss Fuck. SPF is, according to Punknews' admiring reporter, “the most attention-whoring name I’ve ever heard”. Shit Piss Fuck play a kind of “squatter punk / crustified crackrocksteady” music. Their song “Fortified wine” begins:

“If you live in North Carolina or South Dakota or Oklahoma

Then you already know the fucking truth”.

It's unlikely Rod Stewart will be listening to Shit Piss Fuck any time soon. Stewart has just admitted he was “shaken” by the use of foul words used at the Live Earth concerts, and he promised to his own audience three days later to keep his gig free of foul language. Stewart made a pledge to his audience in Coventry last week. "If you hear me swear on stage I'll give you all a tenner” he said. The canny Scotsman Stewart can given himself a monetary incentive for keeping a civil tongue.

The words that shook Stewart in the first place were uttered by comedian Chris Rock. At the gig Rock swore “I’m just jokin’, motherfuckers. Shit” while introducing the Red Hot Chili Peppers at Live Earth. He was cut off by the BBC and its TV presenters Jonathan Ross and Graham Norton apologised to viewers saying that all artists had been warned not to use “bad language during the show”. Showing the priorities of Web 2.0, the Youtube video showing Rock swearing was removed not due to its language but because of a copyright claim.

In the morally uptight world of US free-to-air television, it is a violation of federal law to broadcast indecent or profane programming during certain hours. The law is “vigorously enforced” by the Federal Communications Commission. In 2004, the FCC took action in 12 cases, involving hundreds of thousands of complaints and dished out $8 million in penalties. Under President Bush, the FCC toughened its enforcement penalties by issuing monetary penalties based on each indecent utterance rather than a single penalty for the entire broadcast.

Earlier last month, the 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals made a landmark decision rejecting 2-1 the FCC’s fines against networks in cases that involved "fleeting expletives" such as those Cher and Nicole Ritchie issued during the 2002 and 2003 Billboard Music Awards. The court noted President Bush himself has been caught uttering “shit” on television, meaning the FCC was acting arbitrarily.

Tim Winter is president of the Parents Television Council, an extremist advocacy group that has argued for stricter FCC regulation. Last week he supported Republican presidential hopeful Senator Sam Brownback (R-Kan) who planned to introduce an amendment to strengthen the enforcement of broadcast decency laws to protect children from violence and sexual material on television. The bill would strengthen the FCC’s ability to act against networks using “indecent material”. Winter said they hoped the Senate would affirm the FCC's authority to enforce the broadcast decency laws "rather than letting two judges in New York override strong public opinion”.

Winter, like many conservatives, used protection of children as the overriding reason for restrictive laws. The PTC’s slogan is instructive: "because our children are watching”. It is time to remind Winter and co of a fundamental truth: It's not all about children. Maybe he should listen to "seven-swear-words" comedian George Carlin who said:

Winter, like many conservatives, used protection of children as the overriding reason for restrictive laws. The PTC’s slogan is instructive: "because our children are watching”. It is time to remind Winter and co of a fundamental truth: It's not all about children. Maybe he should listen to "seven-swear-words" comedian George Carlin who said:“Something else I'm getting tired of in this country is all this stupid talk I have to listen to about children. That's all you hear about anymore, children: "Help the children, save the children, protect the children." You know what I say? Fuck the children!”

Carlin finished his plea with a question: “You want to know how to help your kids?" His answer: “Leave them the fuck alone”.

Saturday, July 14, 2007

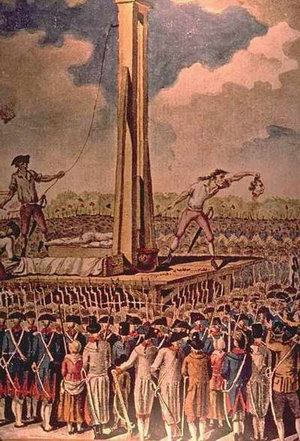

Bastille Day: re-writing the revolution

The French revolution remains one of the seminal events of Western civilisation in the last 500 years. When Henry Kissinger asked Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai what he thought of the French Revolution, Zhou allegedly replied “it's too early to tell”. As well as sweeping away the French monarchy, it laid the seeds for the democratic movement across Europe and created the modern political meanings of the terms left and right. The revolution also had a profound effect on the press.

University of Kentucky history professor Jeremy Popkin discusses the impact of the revolutionary press in “Journals: the New Face of News”. Prior to 1789, the ancien regime had only one royalist daily newspaper, the Journal de Paris which covered cultural rather than political issues. Political periodicals had to be published abroad and imported illegally into the country. Once the regime was discredited and its complex system of censorship, privilege, and manipulation of the foreign press was destroyed, writers and publishers rushed to fill the void created by the events around the first Bastille Day. One of the early newspapers announced in its first edition “we hope our readers will be tolerant of the mistakes that are bound to be committed at the outset of an enterprise as complicated as ours”.

While the new media were colourful and diverse, they failed to last. They were defeated by constraints such as poor levels of literacy and the dependence on wooden hand presses. Nonetheless they formed a useful counterpoint to the new legislative assemblies and were the printed form by which the revolutionary struggle sought political legitimacy. Newspapers would play a central role in the revolutionary process. Key among those who understood the power of the press was journalist and politician J. P. Brissot. Brissot realised that the press was the only means of instituting popular sovereignty in a large country. Only newspapers could permit the conduct of public debate on a national scale. They could allow intellectual leaders to enlighten voters and provide feedback of public opinions to their elected representatives. Through the press, said Brissot, “one can teach the same truth at the same moment to millions of men”.

Once the revolution started, there was an insatiable appetite for news. The Parisian printing industry was transformed and new enterprises ignored guild restrictions and began to produce their own periodicals. Workers left their old jobs to join the growing new and chaotic industry. But there was no security as newcomers continually entered the field, sometimes using the same style and even the same title as established ventures. Two versions of “Ami du roi” defended the honour of the king while there were no less than six differing “Père Duchesnes” based on Jacques Hébert’s radical original.

Freedom of speech remained precarious in the new era. Despite the 1789 Declaration of Rights, each successive revolutionary government harassed those journalists that didn’t support them. Newspapers were forced to live from day to day which gave publishers little time to adopt new technological innovations in the way more secure operations like The Times of London could. The hand-driven presses could not produce in large numbers and subscription remained expensive. Nonetheless Paris boasted 184 periodicals in 1789 which rose to 335 a year later. Many barely lasted one or two issues, but readers could choose from over a hundred publications at any one time.

Freedom of speech remained precarious in the new era. Despite the 1789 Declaration of Rights, each successive revolutionary government harassed those journalists that didn’t support them. Newspapers were forced to live from day to day which gave publishers little time to adopt new technological innovations in the way more secure operations like The Times of London could. The hand-driven presses could not produce in large numbers and subscription remained expensive. Nonetheless Paris boasted 184 periodicals in 1789 which rose to 335 a year later. Many barely lasted one or two issues, but readers could choose from over a hundred publications at any one time. While radical in content, the new papers were conservative in format. They resisted English innovations such as headlines and illustrations and contained few advertisements. The two column formats resembled pre-revolutionary encyclopaedias rather than contemporary newspapers. But there was wide variance in coverage of political events. Some slavishly transcribed the words of politicians in the National Assembly and saw their role as reporting events with fidelity. Others provided their own interpretation of events while others still merely reported the results of the debate. The Journal logographique captured the chaos of the times by portraying the assembly warts and all as a confusing, tumultuous entity that all but made the process unintelligible to its readers.

Brissot’s own Patriote François was considered one the best pro-revolutionary newspapers. Brissot took a partisan position and addressed his comments not only to his readers but to the Assembly deputies themselves. It was devoted to defending “the rights of the people” and often led the agenda on issues. Its clear confident tone and its assurance to readers that deputies also needed advice was an effective approach to presenting ideas without seeming patronising or insulting the public.

Jean-Paul Marat’s agitational pamphlet “Ami du people” was the most celebrated radical paper of the Revolution. His biased view of Assembly proceedings was secondary to his outspoken criticism of its deputies. He often denounced those he disliked in the strongest manner. He was fond of exhorting the people against the Assembly’s “criminal faction”. His emotional reactions were designed to evoke anger against deputies’ treasonable intentions. The Royalist press that flourished in the first years of the Revolution, also shared Marat’s angry rejection of the Assembly but for greatly different reasons. The abbe Royou’s “Ami du roi” described it as a criminal conspiracy that oppressed both the people and the king.

As the power of the press grew, the Assembly became increasing caricatured as disorderly, strife-ridden, anti-democratic and idiotic. Revolutionary deputy J. B. Louvet (himself a journalist) angrily denounced “the eternal domination of writers” over magistrates, representatives and public officials. He warned that the press was a perpetual fomenter of revolution that could destabilise any government if not controlled. France was beginning to understand the paradox of press freedom. The people may choose the government, but also may prefer the press’s view of the government over its own version. While Napoleon resolved the immediate issue by taking firm control of both the government and the media, the problem posed by the role of the free press in a democracy remains with us today. Vive la France.

As the power of the press grew, the Assembly became increasing caricatured as disorderly, strife-ridden, anti-democratic and idiotic. Revolutionary deputy J. B. Louvet (himself a journalist) angrily denounced “the eternal domination of writers” over magistrates, representatives and public officials. He warned that the press was a perpetual fomenter of revolution that could destabilise any government if not controlled. France was beginning to understand the paradox of press freedom. The people may choose the government, but also may prefer the press’s view of the government over its own version. While Napoleon resolved the immediate issue by taking firm control of both the government and the media, the problem posed by the role of the free press in a democracy remains with us today. Vive la France.

Labels:

Bastille Day,

France,

French Revolution,

journalism

Friday, July 13, 2007

US Democrats oppose Libya relations

At least four Democrat senators including Hillary Clinton have threatened to block the appointment of the US’s first ambassador to Libya in 35 years. George W Bush nominated Gene Cretz to fill the vacant role on Wednesday. However Senate Democrats led by Frank Lautenberg (NJ) said no American ambassador should set foot in Tripoli until Libya fulfilled the financial commitments made to the Lockerbie victims' families. Lautenberg and Clinton’s move has been supported by Robert Menendez (NJ) and Charles Schumer (NY). “The US must not pursue fully normalised diplomatic relations with Libya until they fulfil their legal obligations to American families” said Lautenberg yesterday.

Gene Cretz is a possibly provocative choice of ambassador. Cretz is Jewish and currently based in Israel as the deputy chef de mission. He has often been the top US representative in Israel at Jewish memorial services, offering prayers in Hebrew. He spoke at the September 2005 funeral for Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. Cretz is a veteran diplomat who has served at the US embassy in several Arab countries. Prior to serving in Israel, Cretz was the charge d'affaires at the US Embassy in Syria and has also served in Egypt.

However the appointment needs to be confirmed by the Senate and the four Democrats are leading the arguments to push the White House to make Libya do more to account for Lockerbie and the 1986 Berlin disco bombing that killed two US servicemen. The senators want Libya to pay $2.7 billion compensation stipulated in a 2006 agreement with the families of the 270 Lockerbie victims. "A promise made must be a promise kept," said Senator Menendez. "Libya has not made good on its promise to the victims of Pan Am Flight 103, and it must be held responsible."

The US had not had formal diplomat relations with Tripoli since 1980 and Libya was regarded as a pariah state until 2004. The US imposed a trade embargo in 1986 after a period of tension that ended in American air strikes against major targets in the capital, Tripoli, and elsewhere. In 2004 Britain facilitated a thaw in hostilities which enabled Washington to open a diplomatic office in the country. In May 2006 the Bush administration announced it was resuming regular diplomatic relations when it removed removing Gaddafy’s regime from a list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Not everyone in the US was happy with the decision. When Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte planned a visit to Libya to discuss Darfur, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton urged him to use the visit to tell Gaddafy to settle the remaining terrorism cases against his country before the US fully normalise diplomatic relations. Clinton quoted 1985 Egypt Air Flight 648 and the 1985 Rome Airport attack, the reneging of a proposed settlement with the victims of the 1986 bombing of the LaBelle discotheque in Berlin, and the fact they had not fully paid the Lockerbie families.

However new evidence has emerged that has cast doubt on the conviction of the Libyan convicted for the bombing. 55 year old Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi was a former Libyan intelligence officer and head of security for Libyan Arab Airlines who was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2001 on 270 counts of murder for his part in the bombing. The prosecution alleged al-Megrahi arranged for an unaccompanied case containing the bomb to travel on an Air Malta flight from the island's Luqa airport. But the Scottish Sunday Herald claims the airport's then head baggage loader told the Maltese police investigating the disaster that there were no unaccompanied items on the flight to Frankfurt.

However new evidence has emerged that has cast doubt on the conviction of the Libyan convicted for the bombing. 55 year old Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi was a former Libyan intelligence officer and head of security for Libyan Arab Airlines who was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2001 on 270 counts of murder for his part in the bombing. The prosecution alleged al-Megrahi arranged for an unaccompanied case containing the bomb to travel on an Air Malta flight from the island's Luqa airport. But the Scottish Sunday Herald claims the airport's then head baggage loader told the Maltese police investigating the disaster that there were no unaccompanied items on the flight to Frankfurt.

The Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) has now announced it has granted a fresh appeal into al-Megrahi’s conviction. The UN observer appointed to oversee the Lockerbie trial, Dr Hans Köchler, has called on First Minister Alex Salmond to agree to demands for an international inquiry into the handling of the case. In a letter to Salmond, Dr Köchler called for "a full and independent public inquiry of the Lockerbie case and its handling by the Scottish judiciary as well as the British and US political and intelligence establishments". Megrahi’s appeal will not be heard until later next year.

Gene Cretz is a possibly provocative choice of ambassador. Cretz is Jewish and currently based in Israel as the deputy chef de mission. He has often been the top US representative in Israel at Jewish memorial services, offering prayers in Hebrew. He spoke at the September 2005 funeral for Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. Cretz is a veteran diplomat who has served at the US embassy in several Arab countries. Prior to serving in Israel, Cretz was the charge d'affaires at the US Embassy in Syria and has also served in Egypt.

However the appointment needs to be confirmed by the Senate and the four Democrats are leading the arguments to push the White House to make Libya do more to account for Lockerbie and the 1986 Berlin disco bombing that killed two US servicemen. The senators want Libya to pay $2.7 billion compensation stipulated in a 2006 agreement with the families of the 270 Lockerbie victims. "A promise made must be a promise kept," said Senator Menendez. "Libya has not made good on its promise to the victims of Pan Am Flight 103, and it must be held responsible."

The US had not had formal diplomat relations with Tripoli since 1980 and Libya was regarded as a pariah state until 2004. The US imposed a trade embargo in 1986 after a period of tension that ended in American air strikes against major targets in the capital, Tripoli, and elsewhere. In 2004 Britain facilitated a thaw in hostilities which enabled Washington to open a diplomatic office in the country. In May 2006 the Bush administration announced it was resuming regular diplomatic relations when it removed removing Gaddafy’s regime from a list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Not everyone in the US was happy with the decision. When Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte planned a visit to Libya to discuss Darfur, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton urged him to use the visit to tell Gaddafy to settle the remaining terrorism cases against his country before the US fully normalise diplomatic relations. Clinton quoted 1985 Egypt Air Flight 648 and the 1985 Rome Airport attack, the reneging of a proposed settlement with the victims of the 1986 bombing of the LaBelle discotheque in Berlin, and the fact they had not fully paid the Lockerbie families.

However new evidence has emerged that has cast doubt on the conviction of the Libyan convicted for the bombing. 55 year old Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi was a former Libyan intelligence officer and head of security for Libyan Arab Airlines who was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2001 on 270 counts of murder for his part in the bombing. The prosecution alleged al-Megrahi arranged for an unaccompanied case containing the bomb to travel on an Air Malta flight from the island's Luqa airport. But the Scottish Sunday Herald claims the airport's then head baggage loader told the Maltese police investigating the disaster that there were no unaccompanied items on the flight to Frankfurt.

However new evidence has emerged that has cast doubt on the conviction of the Libyan convicted for the bombing. 55 year old Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi was a former Libyan intelligence officer and head of security for Libyan Arab Airlines who was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2001 on 270 counts of murder for his part in the bombing. The prosecution alleged al-Megrahi arranged for an unaccompanied case containing the bomb to travel on an Air Malta flight from the island's Luqa airport. But the Scottish Sunday Herald claims the airport's then head baggage loader told the Maltese police investigating the disaster that there were no unaccompanied items on the flight to Frankfurt.

The Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) has now announced it has granted a fresh appeal into al-Megrahi’s conviction. The UN observer appointed to oversee the Lockerbie trial, Dr Hans Köchler, has called on First Minister Alex Salmond to agree to demands for an international inquiry into the handling of the case. In a letter to Salmond, Dr Köchler called for "a full and independent public inquiry of the Lockerbie case and its handling by the Scottish judiciary as well as the British and US political and intelligence establishments". Megrahi’s appeal will not be heard until later next year.

Thursday, July 12, 2007

Sign of the Times: press coverage in the Victorian era

This essay examines the years 1854 and 1899 through the prism of one of the principle media of the day, The Times of London. Nearly a hundred years later, Mayer considered The Times to be one of the world’s best two newspapers and is now a flagship title in News Limited, one of the largest media organisations on Earth. The years under examination, 1854 and 1899, belong to the period known as Pax Britannica which Harvard’s Albert Imlah defined as the era from 1815 to 1914 commencing with Waterloo and ending at Sarajevo. Lying at the heart of this period were the Victorian years from 1850 to 1900 that roughly defined the boundaries of Britain at the peak of her powers. The internationalism of the 1851 Great Exhibition was the outward sign that British capital was ready to conquer the globe. The new century in 1901 saw the death of Victoria and the inexorable rise of Germany and the US as rival powers. In order to understand a little of these key years, it is instructive to look at the newspapers of the day. By their very ephemeral nature, daily newspapers record events of the quotidian and it is precisely those banal, everyday qualities that define cultural difference.

This essay examines the years 1854 and 1899 through the prism of one of the principle media of the day, The Times of London. Nearly a hundred years later, Mayer considered The Times to be one of the world’s best two newspapers and is now a flagship title in News Limited, one of the largest media organisations on Earth. The years under examination, 1854 and 1899, belong to the period known as Pax Britannica which Harvard’s Albert Imlah defined as the era from 1815 to 1914 commencing with Waterloo and ending at Sarajevo. Lying at the heart of this period were the Victorian years from 1850 to 1900 that roughly defined the boundaries of Britain at the peak of her powers. The internationalism of the 1851 Great Exhibition was the outward sign that British capital was ready to conquer the globe. The new century in 1901 saw the death of Victoria and the inexorable rise of Germany and the US as rival powers. In order to understand a little of these key years, it is instructive to look at the newspapers of the day. By their very ephemeral nature, daily newspapers record events of the quotidian and it is precisely those banal, everyday qualities that define cultural difference.Throughout the Victorian period, The Times was the newspaper of record. For much of the middle of the 19th century, it was Britain’s pre-eminent newspaper under the editorship of J.T. Delane. Established in 1785 it was always a newspaper that led the technical field. When The Times moved to the mechanical (steam) press - which printed ten times the speed of hand presses - it achieved a wide middle class distribution. It was the flagship newspaper for a class that began to take its share in the government of the country. With the gradual reduction in the Stamp Tax and the aid of its free advertisement sheet and occasional double supplement, The Times was the only newspaper to achieve a circulation of 60,000 before 1855.

In 1854 Britain was finally emerging from the depression of the 1840s. Despite the radical intentions of the Chartists, Britain was left relatively unscathed by the European year of revolution in 1848. The economy was opened up to free trade by the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 which had protected landed interest from the proper workings of the market. The country’s new prosperity was reflected in the prominent position of the money market on page five of The Times. Britain was part of a growing international market. The Times noted that although the Paris bourse “exhibited great steadiness,” over in Vienna “a fresh panic appears to have set in” (The Times 1 November 1854 p.5). Some of that panic was a result of the first European war since Napoleonic times. Despite the Pax Britannica, both 1854 and 1899 were war years. 1854 saw the carnage of the Crimean War while the Boer War started in 1899.

The Times was quick to bring news of both these wars to its readers. The speed of news increased rapidly in the 19th century as first the railway and then the telegraph began to form the structure of McLuhan’s global village. As early as 1844, The Times used the new Cook and Wheatstone telegraph to transmit news of the birth of Victoria’s second son Alfred Ernest from Windsor to London in just 40 minutes. In 1854 the Crimean War was the excuse for the British army to build a telegraph across the Black Sea. The Times was not allowed to use the army telegraph but its intrepid war reporter William Howard Russell (who would also go on to represent the newspaper during the 1857 Indian Mutiny) got his messages by steamer across the Black Sea to Varna or Constantinople. From there it was sent “BY SUBMARINE AND BRITISH TELEGRAPH” (The Times 4 November 1854, p. 7) very quickly to London. Yet the Times complained in an editorial that although it was possible for a man to travel to the Crimea in 12 days, news of Sebastopol was taking 18 days to arrive and even then “in the most fragmentary and apocryphal form” (The Times 4 November p.6).

The Times was quick to bring news of both these wars to its readers. The speed of news increased rapidly in the 19th century as first the railway and then the telegraph began to form the structure of McLuhan’s global village. As early as 1844, The Times used the new Cook and Wheatstone telegraph to transmit news of the birth of Victoria’s second son Alfred Ernest from Windsor to London in just 40 minutes. In 1854 the Crimean War was the excuse for the British army to build a telegraph across the Black Sea. The Times was not allowed to use the army telegraph but its intrepid war reporter William Howard Russell (who would also go on to represent the newspaper during the 1857 Indian Mutiny) got his messages by steamer across the Black Sea to Varna or Constantinople. From there it was sent “BY SUBMARINE AND BRITISH TELEGRAPH” (The Times 4 November 1854, p. 7) very quickly to London. Yet the Times complained in an editorial that although it was possible for a man to travel to the Crimea in 12 days, news of Sebastopol was taking 18 days to arrive and even then “in the most fragmentary and apocryphal form” (The Times 4 November p.6).Russell’s reports of casualties and military incompetence caused a storm. The Light (Cavalry) Brigade was annihilated and “entered into action about 700 strong and mustered only 191 on its return (The Times 13 November 1854, p. 6). Never before had the public been treated to such candid and immediate descriptions of war. But it was the page one shipping news such as “Supplies for the Crimea for Varna direct” (The Times 11 November 1854, p.1) as much as Russell’s unbiased reporting that brought the complaint from the British Commander-in-Chief General Simpson that “the enemy never spends a farthing for information. He gets it all for five pence from a London paper”. While The Times’ war coverage also alienated both the Prime Minister of the day, Aberdeen, and his successor Palmerston, it was the personal contact between those two men and The Times’ editor J.T. Delane that gave the newspaper access to vital information in an era where news sources were disorganised.

The newspaper printed a wide variety of opinion on the war. Letter writers expressed their indignation that “Another year of high prices of food…chiefly because war interferes with imports and we have declared our principle foreign food growers to be our enemies” (The Times, 4 November 1854, p.10). The Times even published a Russian account of the war “from the Journal de St Petersbourg” (The Times, 11 November 1854, p.7). Back on the home front, a fundraising public meeting in St Pancras received cheers when it called on all “at home to do all in our power to relieve the anxious minds of those brave men who are so bravely fighting for the cause of freedom against despotic tyranny” (The Times, 4 November 1854, p.8).

With the conflict taking place a safe distance away, the public craved war news. Interest was at fever pitch after the most celebrated battle of the campaign at Balaclava was fought on 25 October. The Times knew how to appeal to patriotism when it framed the “shocking outrage” of an Exeter highway robbery as the story of a victim who deserved “considerable sympathy” because her husband was away with the 8th Hussars in Crimea (The Times, 1 November 1854, p.5).

But there were limits to how far news could travel by telegraph in 1854. The first successful transatlantic cable was not laid until 1866. Cables reached India and China in 1870, Australia a year later, and they arrived in South America in 1874. By 1899 the world was wired. By the end of the century The Times could report on Theodore Roosevelt’s endorsement of President McKinley with a dateline of “NEW YORK June 30” in its newspaper the following day (The Times 1 July 1899 p.7). Meanwhile the money markets could now promptly report on world events as it lamented the “continued marked weakness of Western Australian shares” although “American railroad shares were fairly firm” (The Times, 4 December 1899, p.4).

The Boer War was the major British war of the turn of the century. The Times helped familiarise the names of the faraway places when they devoted a full page to a “map of the NATAL FRONTIER from LADYSMITH to CHARLESTOWN” which, it said was “The Times WAR MAP of SOUTH AFRICA (The Times 2 November 1899, p.4). The war was fought against the 50,000 strong well guerrilla army of Paul Kruger’s Boer Republic who held the initiative in 1899 by invading British Natal. As the year drew to a close, the Boers besieged Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking and might have forced the British into a settlement. On 2 November, the Times reported garrison commander Sir George White’s account of “the Disaster at Ladysmith” where the “losses on our side were numerous” and the position “fell into enemy hands” though the “security of Ladysmith itself was not affected” (The Times, 2 November, 1899 p.5). On the following page, the Times showed it still had the ability to defy authorities when it editorialised that White’s account was not “wholly convincing” (The Times, 2 November 1899, p.6).

Incredibly, the price of The Times was 2d cheaper in 1899 than it was 45 years earlier. In 1854 The Times cost 5d. Although the advertising tax had been removed the year before, it would be another year before the last of the Stamp taxes were removed on newspapers. That same year Cobden said of The Times that at 5d it was as cheap as any paper in the world. But he cautioned, “it was no consolation to the poor peasant, whose earnings were 15d and 18d a day”. When the maximum weight of a 1d postage was reduced below the Times average weight, the newspaper’s growth was impaired and the new Daily Telegraph became the first successful metropolitan penny daily. The Times meanwhile sold regularly at 3d from 1861 to 1913 justifying the price by upholding its unique character. Cobden’s complaint was still valid at the end of the century. The price of the newspaper was beyond the reach of many. Charles Booth estimated that one third of the people of London lived below the poverty line at the end of the century.

The Times unbroken column layout of the political pages remained unchanged in the years between 1854 and 1899 and was typical of what Morison called “the upper- and middle class typographical orthodoxy” of the early 19th century (Morison in Wiener 1988, p.51). However the newspaper changed in other ways. In 1858, The Times switched to stereotypes on cylinders which enabled production to be multiplied (Lee 1976, p.56). In the 1880s newspapers changed from printing on rags to woodpulp which vastly reduced the cost of newsprint, though at the cost of durability (Lee 1976, p.57).

Despite the technological changes, The Times was slow to embrace the techniques of new journalism. Illustrations were rare, the war wasn’t front page news in 1854 or 1899. The first three pages were reserved for classified ads, births, deaths, personal messages and shipping news. On Christmas Day 1854 the Times front page told of the death of Mrs Dorothy Bagnall, “35 years the faithful and valued servant of the family of the Marquis of Anglesey” (The Times 25 December 1854 p.1). In November 1899 similar messages abounded. Instead of reading about the Siege of Mafeking, Times page one readers were asked to sample the “dainty cuisine” of Fredericks Modern English hotels and were offered an imploring plea to “send power of attorney to sign for son. Absolutely necessary” (The Times, 1 November 1899, p.1). The commercial prosperity of The Times depended on a large number of these types of small advertisements.

Despite the technological changes, The Times was slow to embrace the techniques of new journalism. Illustrations were rare, the war wasn’t front page news in 1854 or 1899. The first three pages were reserved for classified ads, births, deaths, personal messages and shipping news. On Christmas Day 1854 the Times front page told of the death of Mrs Dorothy Bagnall, “35 years the faithful and valued servant of the family of the Marquis of Anglesey” (The Times 25 December 1854 p.1). In November 1899 similar messages abounded. Instead of reading about the Siege of Mafeking, Times page one readers were asked to sample the “dainty cuisine” of Fredericks Modern English hotels and were offered an imploring plea to “send power of attorney to sign for son. Absolutely necessary” (The Times, 1 November 1899, p.1). The commercial prosperity of The Times depended on a large number of these types of small advertisements.The Times newspaper captured an era in flux. While writers like Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf described the Victorian age as “the descent of some dismal cloud” over Britain, it was an era of great dynamism and the birth of the modern age. Victorians bore the brunt of a bewildering world-shrinking revolution. The Times of London faithfully documented this revolution in its own quotidian fashion.

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

Mixed results in World Bank corruption report

A new World Bank report has praised African nations for their fight against corruption. The report measured the quality of governance in 212 countries from 1996 to 2006 and found Africa had shown the greatest improvement. The report did, however, find that the gains and losses balanced out such that the average quality of governance worldwide over the past decade has not improved much. Finland, Iceland, Denmark Norway and New Zealand were judged the least corrupt countries in the world while Somalia, Myanmar (Burma), Equatorial Guinea, Haiti and Zimbabwe ranked most corrupt.

A new World Bank report has praised African nations for their fight against corruption. The report measured the quality of governance in 212 countries from 1996 to 2006 and found Africa had shown the greatest improvement. The report did, however, find that the gains and losses balanced out such that the average quality of governance worldwide over the past decade has not improved much. Finland, Iceland, Denmark Norway and New Zealand were judged the least corrupt countries in the world while Somalia, Myanmar (Burma), Equatorial Guinea, Haiti and Zimbabwe ranked most corrupt. The World Bank’s Daniel Kaufmann, co-author of the report and director of the banks knowledge-sharing and training arm, said that bribery is costing world $1 trillion a year with the billion people living in extreme poverty worst affected. “The burden of corruption falls disproportionately on the bottom billion people living in extreme poverty,” he said. Kaufman said improvements in governance are critical for aid effectiveness and for sustained long-run growth.

The report entitled Governance Matters, 2007: Worldwide Governance Indicators 1996-2006 highlighted the number of African countries that had made great strides in improving various aspects of government. Using criteria such as accountability, free media, political stability,government effectiveness, regulatory quality, the rule of law and control of corruption, the report covered 212 countries and territories and drew on 33 different data sources. It captured the views of tens of thousands of survey respondents worldwide, as well as thousands of experts in the private, NGO and public sectors.

Some countries such as Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Eritrea, Ivory Coast and Belarus had regressed in the timeframe of the survey. But others are doing well: Kenya, Niger, Sierra Leone, on leadership accountability, Algeria and Liberia on the rule of law, Algeria, Angola, Libya, Rwanda and Sierra Leone on political stability and Tanzania on corruption. Outside Africa, those making significant gains included Indonesia, Ukraine, Columbia, Turkey and Afghanistan. Meanwhile corruption is on the rise in Bangladesh, Poland, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova and Pakistan.

Management of corruption is now a key World Bank benchmark. Many of the debts of the world's poorest countries have been written off under the Bank's Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative and increased aid flows to them on condition that they stamp out corruption. HIPC started in 1996 and was enhanced in 1999 as an outcome of a comprehensive review by the International Development Association (IDA) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). HIPC’s debt-burden thresholds were adjusted downward, which enabled more countries to qualify for larger volumes of debt relief.

The report showed that corruption in the US has significantly worsened in the last decade. The World Bank scored the US on the same measure as Chile. Similar surprises showed emerging economies such as Botswana, Costa Rica and Lithuania, scored higher on the rule of law and corruption than two industrialized countries Italy and Greece. Daniel Kaufman the report showed the power of data “It begins to challenge these long-held popular notions that the rich world has reached nirvana in governance,” he said.

However Kaufman also admitted that the Bank’s own recent scandal involving former President Paul Wolfowitz has impacted the credibility of both the report and the bank itself. Wolfowitz was forced to resign in May after he violated a World Bank ethics rule forbidding personal relationships between bank employees and their supervisors. Kaufmann said countries rightly asked the Bank, "What right do you have of rating the world when you first have to rate yourselves? It has to start at home."

However Kaufman also admitted that the Bank’s own recent scandal involving former President Paul Wolfowitz has impacted the credibility of both the report and the bank itself. Wolfowitz was forced to resign in May after he violated a World Bank ethics rule forbidding personal relationships between bank employees and their supervisors. Kaufmann said countries rightly asked the Bank, "What right do you have of rating the world when you first have to rate yourselves? It has to start at home."

Labels:

corruption,

government,

World Bank,

world politics

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

Nigeria and Cameroon: haunted by colonial borders

The border dispute between Nigeria and Cameroon is likely to drag on after the border commission said it needs more than $24 billion to complete its final demarcation exercise on the 1,600 km land and maritime boundaries between the countries. The Nigerian commission representative said that the original budget of $12 billion (donated by the UK, Germany, France, the EU, the Nigerian and Cameroonian governments) is insufficient and they need “more than double that amount of money” to finish the job. The areas of dispute between the countries are the Bakassi Peninsula, the Lake Chad area and the maritime boundary.

The border dispute between Nigeria and Cameroon is likely to drag on after the border commission said it needs more than $24 billion to complete its final demarcation exercise on the 1,600 km land and maritime boundaries between the countries. The Nigerian commission representative said that the original budget of $12 billion (donated by the UK, Germany, France, the EU, the Nigerian and Cameroonian governments) is insufficient and they need “more than double that amount of money” to finish the job. The areas of dispute between the countries are the Bakassi Peninsula, the Lake Chad area and the maritime boundary.The Cameroon - Nigeria Mixed Commission was the creation of the UN to resolve the dispute after a 2002 ruling by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the land and maritime boundary between the two countries. At the centre of the dispute lies the Bakassi Peninsula. The peninsula is a tiny landstrip of mangrove swamp and consisting of a series of fluvial islands covering approximately 50 square kilometres. It is inhabited by some dozens of villages. Both sides claim ownership over its rich fishing waters in the Gulf of Guinea and its possible oil reserves.

The origins (pdf) of the dispute date back to colonial times. In 1884 Britain justified its takeover of the region by signing a Treaty of Protection with the Obong of Calabar. Britain promised the Obong and his people the protection of the British armed forces in return for fealty to the crown. Over the course of the 30 years Britain and Germany formalised the borders of their African possessions. By 1913 the countries had precisely marked the demarcation of the Anglo-German Boundary between Nigeria and Kamerun from Yola to the Cross River. Britain ceded the Bakassi peninsula to Germany in return for port access via the offshore border.

When World War I broke out, Britain invaded German Kamerun and the country became spoils of war in the Versailles Treaty. The country was split up into British and French mandates. Britain gained Southern Cameroon and Bakassi which it administered contiguously with Nigeria though it never formally merged the entities. After World War II, the UN ratified the 1913 borders once more. French Cameroons became independent in 1960 as did British Nigeria. The people of the Bakassi were left in legal limbo by the two new countries either side of it. While some residents wanted complete independence, the UN held a plebiscite that offered only union with Nigeria or Cameroon.

And so in 1961 anglophone Southern British Cameroon was merged with francophone Cameroon. Nigeria confirmed the result and installed a consul in Buea, former capital of British Cameroon. The situation changed after Biafra, the Eastern-most province of Nigeria, declared its independence. Nigeria regained control in 1970 after a bitter three year civil war. While Nigeria was busy fighting, Cameroon began exploring in the oil rich waters off Bakassi. The two countries established a boundary commission to establish which waters belonged to Cameroon and which belonged to Nigeria. Negotiations dragged on through the 1970s.

But despite an agreement in 1975 the border remained fluid. It was in effect a double jurisdiction for decades. Both states used force to collect taxes and relocate inhabitants to zones controlled by them. Border skirmishes were common. Reports of abductions, looting and torture were rife carried out by both Cameroonian gendarmes and the Nigerian army. After Nigerian strongman Sani Abacha sent troops to Bakassi in 1994, Cameroon took its sovereignty claim to the ICJ. The case took eight years to resolve.

In 2002 the ICJ ruled on the matter. It ruled in favour of Cameroon based on the 1913 colonial border between Britain and Germany. The two heads of state agreed to abide by the decision. Then Nigerian President Obasanjo hailed the agreement as “a great achievement in conflict prevention, which practically reflects its cost effectiveness when compared to the alternative of conflict resolution”.

In 2002 the ICJ ruled on the matter. It ruled in favour of Cameroon based on the 1913 colonial border between Britain and Germany. The two heads of state agreed to abide by the decision. Then Nigerian President Obasanjo hailed the agreement as “a great achievement in conflict prevention, which practically reflects its cost effectiveness when compared to the alternative of conflict resolution”.But Obasanjo went home to find outrage over the decision and Nigeria has since dragged its heels. At the time UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan noted the “stunning” cost-effectiveness of the Mixed Commission. With the project only one third complete and a possible end cost of $36 billion, Annan’s successor Ban-Ki Moon is unlikely to share the joy.

Labels:

African politics,

Cameroon,

Nigeria,

United Nations

Monday, July 09, 2007

Red Mosque: portents of Pakistan’s Islamic revolution?

The siege at Pakistan’s red mosque entered a new and dangerous stage yesterday when a Pakistani army commander was shot and killed during an operation to blast holes in the mosque's perimeter walls. Lt. Col. Haroon-ul-Islam was killed and three other officers were wounded during a failed operation to free women and children authorities believe are being used as human shields. The six-day old siege in the capital Islamabad is being held by followers of the cleric Abdul Rashid Ghazi. The Government says those inside are members of the illegal Harkat Jihad-e-Islam organisation which is suspected of killing US journalist Daniel Pearl.

The siege at Pakistan’s red mosque entered a new and dangerous stage yesterday when a Pakistani army commander was shot and killed during an operation to blast holes in the mosque's perimeter walls. Lt. Col. Haroon-ul-Islam was killed and three other officers were wounded during a failed operation to free women and children authorities believe are being used as human shields. The six-day old siege in the capital Islamabad is being held by followers of the cleric Abdul Rashid Ghazi. The Government says those inside are members of the illegal Harkat Jihad-e-Islam organisation which is suspected of killing US journalist Daniel Pearl.At least 24 people have died so far in the stand-off at the mosque. Hundreds of troops surround the compound while there are disputed numbers of how many are inside. Ghazi himself says he has two thousand followers inside while his elder brother Maulana Abdul Aziz puts the figure at 850. While Ghazi remains inside with at least 60 heavily armed followers, his brother was arrested on Wednesday after he tried to escape from the mosque disguised in a burqa.

Abdul Rashid Ghazi came from an elite Pakistani family. His father Abdullah Aziz was the head of the Red Mosque. Ghazi gained his master’s degree in International Relations from one of Pakistan's most prominent universities, the Quaid-e-Azam University in Islamabad. Ghazi joined the Pakistani Government and also worked for UNESCO. He lived a relatively western lifestyle until a life changing event in 1998. In that year his father Abdullah was murdered inside the mosque; the assassins were believed to be members of a rival Islamic group. Abdul Aziz took over the mosque and his brother dropped his western lifestyle to join him. The two quickly went on a hardline Islamic path. Ghazi now says he has chosen “martyrdom” over negotiations and hopes that his death would spark an Islamic revolution in Pakistan.

Lal Masjid or Red Mosque is Islamabad’s central mosque and is sited less than 3km away from the office of President Musharraf. The mosque is the favourite place of worship of Pakistan’s elite including members of the shadowy intelligence force ISI. Former president Zia-ul-Haq was said to be very close to Abdullah Aziz. The mosque has two madrassas (religious schools) which house thousands of students, one for women attached to the mosque itself and one for men a few minutes drive away.

Since the brothers took over, the mosque has become been a centre of radical Islamic learning. Though their rhetoric was toned down after Pakistan was co-opted into the so-called “War on Terror”, Lal Masjid remained strongly supportive of a “jihad against America”. Pakistani security forces tried to raid the mosque following the London in 2005 but were met by baton-wielding women who refused to let them enter the compound. That same year Abdul Aziz issued a fatwa declaring that Pakistani soldiers killed fighting militants in the northern tribal areas could not be given Muslim funeral rites.

In the last 12 months mosque students began challenging the writ of government by setting up a Taliban-style judicial system based on Sharia Law and acting as vigilantes to stop what they see as “moral crime”. The trouble escalated in January when the government ordered the demolition of what it called an illegal mosque. When the government didn’t act to stop the occupation of the building, the protesters became emboldened and took to the streets.

On Tuesday last week, a top level meeting of the Pakistani Government gave the order to launch an operation against the mosque. Authorities shut down the electricity supply to the mosque, closed two adjacent markets and blocked all roads into the area. Students carried Kalashnikovs and wore gas masks took up positions behind sandbags and dirt bunkers chanting “Jihad! Jihad!”, as police in riot vans fired volleys of tear gas. In the gun battle that followed 20 people were killed and over 100 were injured.

Six days on the students remain barricaded inside the mosque compound. On Saturday General Musharraf gave them a "surrender or die" ultimatum. While hundreds initially emerged, departures have dried up leading to the conclusion that only hardcore followers of the brothers remain. However there is also the possibility that some remain against their will. One man with a relative inside told AP that there are 250 hostages inside the mosque. Bakht Sher said he spoke by mobile phone with his nephew who told him that the hostages were being held in a basement area of the complex. He said his nephew saw the body of a man who had been shot dead while trying to escape.

Musharraf now has the dilemma of trying to storm a heavily armed compound without making martyrs of those inside. Those remaining inside the compound have apparently taken oaths on the Koran to fight to the death in the hope of sparking an Islamic revolution in Pakistan. Musharraf knows that he must move cautiously to avoid antagonising the country’s powerful Islamic clerics. At the same time he knows that every day the crisis drags on is a victory for Abdul Rashid Ghazi.

Musharraf now has the dilemma of trying to storm a heavily armed compound without making martyrs of those inside. Those remaining inside the compound have apparently taken oaths on the Koran to fight to the death in the hope of sparking an Islamic revolution in Pakistan. Musharraf knows that he must move cautiously to avoid antagonising the country’s powerful Islamic clerics. At the same time he knows that every day the crisis drags on is a victory for Abdul Rashid Ghazi.The implications are already being felt elsewhere in Pakistan. Troops were deployed to Malakand and Dir district in North West Frontier Province (NWFP) after a militant mullah Maulana Fazlullah declared holy war on the Government because of its handling of the siege in Islamabad. Pakistan say there are close links between Fazlullah and the Red Mosque with many of the mosque’s students from remote tribal areas such as NWFP. Meanwhile the Government has called for patience in Islamabad. "We will have to play this wait game,” said Pakistan's information minister, Tariq Azim. “It may take a while, but I think we will succeed in the end."

Sunday, July 08, 2007

Andrew Bartlett launches senate re-election campaign

Democrat Senator Andrew Bartlett launched his Senate re-election campaign today at the QUT Gardens Theatre in Brisbane. Bartlett has been a federal Senator for Queensland since 1997 and is now seeking his third term. Around 250 people turned up today for the launch and heard a speech from former Queensland Democrat senator John Cherry, endorsements from high profile citizens such Julian Burnside and Frank Brennan and finally the keynote speech from Senator Bartlett.

Democrat Senator Andrew Bartlett launched his Senate re-election campaign today at the QUT Gardens Theatre in Brisbane. Bartlett has been a federal Senator for Queensland since 1997 and is now seeking his third term. Around 250 people turned up today for the launch and heard a speech from former Queensland Democrat senator John Cherry, endorsements from high profile citizens such Julian Burnside and Frank Brennan and finally the keynote speech from Senator Bartlett.The launch was kicked off by Democrat State President Liz Oss-Emer who asked Aboriginal elder Aunty Carol Currie to issue the welcome to traditional lands. Then former Senator John Cherry spoke. Cherry was a trenchant choice of speaker. His defeat in the 2004 election by 1 per cent after 159 counts elected Liberal Russell Trood and handed control of the Senate to the Government for the first time since 1981. Cherry stated he was the victim of an electorate that “forgot to think” and it must not happen again. Cherry stated that the Democrats were instrumental in turning the Senate into the most powerful and effective house of review in the world prior to 2004. They now have three months before the next election to put their case and urge the voters to “think before they vote”.

There then followed five testimonials. Julian Burnside QC described Bartlett as “completely honest” and performing a crucial role in senate committees. Yassmin Abdel-Magied (young Australian Muslim of the year 2007) praised his support of Muslim youth. Afghan born and former Nauru detainee Chaman Shah said that Bartlett was the only politician who gave the detainees hope. Bobby Whitfield of the Liberian Association of Queensland praised Bartlett for his practical approach and support for those marginalised and oppressed. Finally Frank Brennan paid testament to the “power of good” Bartlett did especially for minority groups.

Andrew Bartlett began his own speech by thanking those who turned up. He appealed to his supporters to take the campaign out in the community as he cannot compete with the advertising budgets of the big parties. He said Senator Cherry reminded the audience of how the Democrats began after the constitutional crisis of 1975. Bartlett pointed to the pledge made by former Queensland Democrat Senator Michael Macklin where he promised not to abuse power by blocking supply and bringing down the government. Bartlett made a similar pledge.

Bartlett then launched into policies. He was critical of the Howard Government’s WorkChoices legislation which he said “must go”. Bartlett called for more flexibility in the workplace without exploitation of employees. He re-affirmed his commitment to fight nuclear power and condemned what he called “the drastic decline in numbers of Senate enquiries”. Bartlett said we needed laws to protect our freedoms and called for a Bill of Rights.

Internationally he supported those in China, Vietnam, Burma, West Papua and Zimbabwe who fight for freedoms we take for granted in Australia. Bartlett claimed that the independent voice of the smaller parties gave them greater freedom to speak out on human rights issues. However he also supported “those who have no voice” in this country. He pointed to the example of ex-service personnel who are often neglected on their return.

Bartlett opposed what he called the unrepresentative views that emerged in 1998 in Queensland epitomised by the Pauline Hanson scare campaigns. But, he said, it was not about opposing Hanson herself but opposing the anti-refugee actions supported by both major parties, as well as opposing the “anti-migrant dog whistling” and the public attacks on African and Muslim refugees. Bartlett pointed out there was a great diversity in the wider community “if only we listened to them and gave them the opportunity to speak”. Bartlett said a strong democratic framework does not occur by accident, it must be encouraged.

Bartlett then went onto indigenous policy. He said the first priority must be clearing the massive backlog of land rights claims. The Stolen Generations report needs to be addressed as well as the Stolen Wages Inquiry. Bartlett said that “no one should wrap themselves in the flag” without acknowledging that Aboriginals lack what most of the rest of the population enjoy. He also said the wrongs of the past cannot be undone but must be acknowledged. Bartlett supported the move to protect NT’s children but it needs sufficient resources to make it work for as long as it takes not for “the ten second grab”. Bartlett said he wanted to see action taken against child abuse in all communities.

Bartlett then went onto indigenous policy. He said the first priority must be clearing the massive backlog of land rights claims. The Stolen Generations report needs to be addressed as well as the Stolen Wages Inquiry. Bartlett said that “no one should wrap themselves in the flag” without acknowledging that Aboriginals lack what most of the rest of the population enjoy. He also said the wrongs of the past cannot be undone but must be acknowledged. Bartlett supported the move to protect NT’s children but it needs sufficient resources to make it work for as long as it takes not for “the ten second grab”. Bartlett said he wanted to see action taken against child abuse in all communities. Bartlett then addressed the problem of growth in greenhouse emissions. He said the Democrats were responsible for the first parliamentary enquiry on the subject in 1991 and that government inaction since then amounts to “culpable negligence”. He said the decisions we need to make are tougher now than they were 15 years ago. The issue demands “honesty, common sense and working together” and everyone must change their behaviours. Bartlett discussed his own goal to be carbon neutral, cut emissions and offset the rest through a trading scheme.

Bartlett then discussed taxation and said “the easiest thing to do is offer tax cuts”. But Bartlett reiterated the Democrat position since the 1980s that what was required was indexation of income tax thresholds. He also reiterated his position against the proposed new dams in Queensland at Traveston and Wyaralong which he condemned as a “waste of money”.

Bartlett concluded by saying this federal election was “like no other” and Queensland was a key battleground. He exhorted his supporters to “take on the job to continue the fight”. He said the Democrats offer the community a “strong, effective voice for the issues that matter”. He closed the launch by repeating his campaign slogan “choose common sense” and asked his supporters to make every vote count.

Andrew Bartlett is a former leader of the Democrats and is now its deputy leader. The party has been long embattled with a declining vote in the last two elections. They could lose all parliamentary representation in the next election. The term of all four remaining senators (Bartlett, Andrew Murray, Natasha Stott Despoja and leader Lynn Allison) expires in June 2008 with both Murray and Stott Despoja announcing their intentions not to re-contest.

In 1997, he was chosen by the Queensland parliament to replace Cheryl Kernot after she defected to Labor. In his maiden speech (11 November 1997) Bartlett described his first political experience as a nine year old helping his mother hand out how-to-vote cards for the DLP outside his local school. The event introduced Bartlett to political disappointment at an early age; the DLP was wiped off the political map in that election.

Andrew Bartlett graduated in arts and social work from the University of Queensland. During this time he also played in local bands and became involved with 4ZZZ community radio both on air and behind the scenes. After a year of social work, Bartlett got his break in politics in 1990 when he was appointed electoral officer to Democrat senator Cheryl Kernot. After three years he left to work for another Queensland Democrat senator John Woodley whom he served until his own appointment to parliament.

Bartlett is a strong Senate campaigner, a thoughtful blogger and an active citizen who is often found at protests, demonstrations and public meetings throughout Queensland and elsewhere. He has served on numerous high profile parliamentary commissions including A Certain Maritime incident (Siev X) and is a strong believer in the power of the Senate as body of review.

Bartlett is a strong Senate campaigner, a thoughtful blogger and an active citizen who is often found at protests, demonstrations and public meetings throughout Queensland and elsewhere. He has served on numerous high profile parliamentary commissions including A Certain Maritime incident (Siev X) and is a strong believer in the power of the Senate as body of review. With his party polling at five per cent or under and a strong challenge likely from Larissa Waters of the Greens, it will be a very tough ask for Bartlett to win re-election. In his favour is his strong image of integrity and excellent record in the Senate. Depending on how well he does on preference deals with the slew of other parties expected to line up, he may yet be returned to parliament for a third term.

Saturday, July 07, 2007

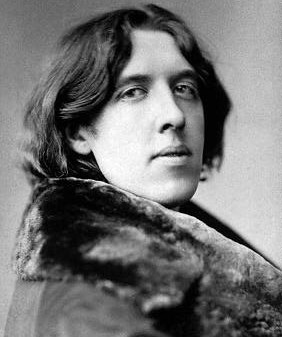

The Importance of being Oscar Wilde

The Indian online outlet IndiaTimes has broached a sub-continental taboo subject: the legalisation of homosexuality. In India homosexuality is treated as a criminal offence according to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which was framed in 1860. In an anonymous article this week, IndiaTimes claimed five per cent of the total sexually active Indian population is estimated to be homosexual and there is active lobbying for repealing the IPC clause in legal and political circuits.

The Indian online outlet IndiaTimes has broached a sub-continental taboo subject: the legalisation of homosexuality. In India homosexuality is treated as a criminal offence according to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which was framed in 1860. In an anonymous article this week, IndiaTimes claimed five per cent of the total sexually active Indian population is estimated to be homosexual and there is active lobbying for repealing the IPC clause in legal and political circuits. In opening the article it mentioned Oscar Wilde, who unlike Indians they said, “could afford to have a lyrical view on homosexuality”. While it is fair to be sympathetic to the plight of the Indian gay community in a country where the topic remains taboo (especially with the IPC allowing a maximum sentence of life imprisonment for the “crime”), Oscar Wilde’s view of his own sexuality was far from lyrical. Wilde himself was imprisoned for “buggery” and died a pauper in Paris.

Oscar Wilde was born in Dublin of a Protestant family who supported the cause of Irish nationalism. However they also belonged to the ruling class and were comfortable with their peers in London. His father, Sir William Wilde, was a famous eye surgeon and his mother Jane Francesca Elgee wrote poetry under the name of Speranza. Her poems were published in the Nationalist journal “the Nation”. When the British arrested the journal’s editor Charles Gavan Duffy (who was transported to Australia where he became a successful politician) in 1848, Lady Wilde wrote a scathing editorial that the British used in Gavan Duffy’s prosecution. However they did not arrest her ladyship.

Oscar was their hugely talented second son. He studied at Trinity College Dublin where he was a brilliant Greek scholar and was granted a scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford. In 1878, he graduated with a double first in classical moderations and literae humaniores. After a brief and unsuccessful love affair in Dublin, Wilde moved to London. When Sir William died in 1879, Lady Wilde followed her son and moved her salon to London.

Wilde quickly established a reputation for himself as a dandy and a wit before he even published his first book of poems. When he travelled to the US on a lecture tour in 1881 everything he said and did was widely reported. He returned to England in 1883 where he met and married Constance Lloyd. Wilde described her as “a grave, slight, violet-eyed little Artemis”. Oscar and Constance settled into what passed for Victorian domestic bliss and they had two sons Cyril and Vyvyan.

In 1890, he wrote his only novel “The Picture of Dorian Gray”. The novel had a strong homoerotic overtone with a male artist infatuated by the beauty of young man (Gray) whom he painted. The Daily Chronicle’s review said the book contained “one element...which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it”. Within 12 months, Wilde met the man who would change his life: Alfred Douglas, or as Wilde called him “Bosie”.

Their torrid relationship is captured in Wilde’s many letters to Bosie. “Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry”. “[Y]ou break my heart – I’d sooner be rented all day, than have you bitter, unjust and horrid”. “London is a desert without your dainty feet”. Bosie, however shared some destructive qualities of his father, a tyrannical nature and extreme volatility.

But love did get the creative juices going. Between 1891 and 1894 Wilde wrote his four best plays. The first three (Lady Windermere’s Fan, A Woman of No Importance and An Ideal Husband) were effortless and witty but thinly plotted and poorly characterised.

But it was his fourth play The Importance of Being Earnest where it all came together spectacularly. However the play itself seemed to have foreboding of Wilde’s personal drama to come. There is Jack’s fictitious brother who expresses a desire to be buried in Paris. Gwendolyn states that a man who neglects domestic duties “becomes painfully effeminate” while Lady Bracknell’s line “to miss more [trains] might expose us to comment on the platform” foresaw the platform jeering Wilde faced when being taken to prison.

But it was his fourth play The Importance of Being Earnest where it all came together spectacularly. However the play itself seemed to have foreboding of Wilde’s personal drama to come. There is Jack’s fictitious brother who expresses a desire to be buried in Paris. Gwendolyn states that a man who neglects domestic duties “becomes painfully effeminate” while Lady Bracknell’s line “to miss more [trains] might expose us to comment on the platform” foresaw the platform jeering Wilde faced when being taken to prison. Nevertheless Wilde was at the height of his fame in 1895. Two plays opened that year. An Ideal Husband opened on 3 January with the Prince of Wales, Arthur Balfour and Neville Chamberlain in the audience. On 14 February,The Importance of Being Earnest opened to great success. He had two full houses in London theatres. The New York Times said that “Oscar Wilde may be said to at last, and by a single stroke, put his enemies under his feet”.

But those enemies didn’t stay there long. The Marquess of Queensbury (who gave his name to the rules of boxing), Bosie’s father, was thwarted from attending the opening night of “Earnest” but he did leave “a grotesque bouquet of vegetables”. Douglas himself was abroad and missed the opening night but returned to London later that month. He came to stay with Wilde at Piccadilly’s Avondale Hotel. He moved out after Wilde showed no enthusiasm to share the room with a third man.