The Indian online outlet IndiaTimes has broached a sub-continental taboo subject: the legalisation of homosexuality. In India homosexuality is treated as a criminal offence according to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which was framed in 1860. In an anonymous article this week, IndiaTimes claimed five per cent of the total sexually active Indian population is estimated to be homosexual and there is active lobbying for repealing the IPC clause in legal and political circuits.

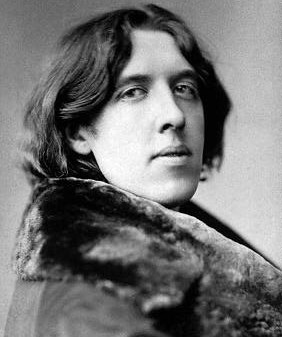

The Indian online outlet IndiaTimes has broached a sub-continental taboo subject: the legalisation of homosexuality. In India homosexuality is treated as a criminal offence according to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which was framed in 1860. In an anonymous article this week, IndiaTimes claimed five per cent of the total sexually active Indian population is estimated to be homosexual and there is active lobbying for repealing the IPC clause in legal and political circuits. In opening the article it mentioned Oscar Wilde, who unlike Indians they said, “could afford to have a lyrical view on homosexuality”. While it is fair to be sympathetic to the plight of the Indian gay community in a country where the topic remains taboo (especially with the IPC allowing a maximum sentence of life imprisonment for the “crime”), Oscar Wilde’s view of his own sexuality was far from lyrical. Wilde himself was imprisoned for “buggery” and died a pauper in Paris.

Oscar Wilde was born in Dublin of a Protestant family who supported the cause of Irish nationalism. However they also belonged to the ruling class and were comfortable with their peers in London. His father, Sir William Wilde, was a famous eye surgeon and his mother Jane Francesca Elgee wrote poetry under the name of Speranza. Her poems were published in the Nationalist journal “the Nation”. When the British arrested the journal’s editor Charles Gavan Duffy (who was transported to Australia where he became a successful politician) in 1848, Lady Wilde wrote a scathing editorial that the British used in Gavan Duffy’s prosecution. However they did not arrest her ladyship.

Oscar was their hugely talented second son. He studied at Trinity College Dublin where he was a brilliant Greek scholar and was granted a scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford. In 1878, he graduated with a double first in classical moderations and literae humaniores. After a brief and unsuccessful love affair in Dublin, Wilde moved to London. When Sir William died in 1879, Lady Wilde followed her son and moved her salon to London.

Wilde quickly established a reputation for himself as a dandy and a wit before he even published his first book of poems. When he travelled to the US on a lecture tour in 1881 everything he said and did was widely reported. He returned to England in 1883 where he met and married Constance Lloyd. Wilde described her as “a grave, slight, violet-eyed little Artemis”. Oscar and Constance settled into what passed for Victorian domestic bliss and they had two sons Cyril and Vyvyan.

In 1890, he wrote his only novel “The Picture of Dorian Gray”. The novel had a strong homoerotic overtone with a male artist infatuated by the beauty of young man (Gray) whom he painted. The Daily Chronicle’s review said the book contained “one element...which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it”. Within 12 months, Wilde met the man who would change his life: Alfred Douglas, or as Wilde called him “Bosie”.

Their torrid relationship is captured in Wilde’s many letters to Bosie. “Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry”. “[Y]ou break my heart – I’d sooner be rented all day, than have you bitter, unjust and horrid”. “London is a desert without your dainty feet”. Bosie, however shared some destructive qualities of his father, a tyrannical nature and extreme volatility.

But love did get the creative juices going. Between 1891 and 1894 Wilde wrote his four best plays. The first three (Lady Windermere’s Fan, A Woman of No Importance and An Ideal Husband) were effortless and witty but thinly plotted and poorly characterised.

But it was his fourth play The Importance of Being Earnest where it all came together spectacularly. However the play itself seemed to have foreboding of Wilde’s personal drama to come. There is Jack’s fictitious brother who expresses a desire to be buried in Paris. Gwendolyn states that a man who neglects domestic duties “becomes painfully effeminate” while Lady Bracknell’s line “to miss more [trains] might expose us to comment on the platform” foresaw the platform jeering Wilde faced when being taken to prison.

But it was his fourth play The Importance of Being Earnest where it all came together spectacularly. However the play itself seemed to have foreboding of Wilde’s personal drama to come. There is Jack’s fictitious brother who expresses a desire to be buried in Paris. Gwendolyn states that a man who neglects domestic duties “becomes painfully effeminate” while Lady Bracknell’s line “to miss more [trains] might expose us to comment on the platform” foresaw the platform jeering Wilde faced when being taken to prison. Nevertheless Wilde was at the height of his fame in 1895. Two plays opened that year. An Ideal Husband opened on 3 January with the Prince of Wales, Arthur Balfour and Neville Chamberlain in the audience. On 14 February,The Importance of Being Earnest opened to great success. He had two full houses in London theatres. The New York Times said that “Oscar Wilde may be said to at last, and by a single stroke, put his enemies under his feet”.

But those enemies didn’t stay there long. The Marquess of Queensbury (who gave his name to the rules of boxing), Bosie’s father, was thwarted from attending the opening night of “Earnest” but he did leave “a grotesque bouquet of vegetables”. Douglas himself was abroad and missed the opening night but returned to London later that month. He came to stay with Wilde at Piccadilly’s Avondale Hotel. He moved out after Wilde showed no enthusiasm to share the room with a third man.

Meanwhile Queensbury wasn’t done making trouble. Four days after Earnest’s opening night he left a card at Wilde’s club which read “To Oscar Wilde posing as a Somdomite [sic]”. Wilde didn’t pick it up until ten days later. In a letter he immediately sent to journalist and art critic, Robert Ross, Wilde foresaw how the rest of his life would eventuate: “I don’t see anything now but a criminal prosecution. My whole life seems ruined by this man”. Ross advised Wilde to take no action and go to Paris.

But Wilde was in no mood to forgive the insult, however badly spelt. It was clear that Queensbury was in possession of incriminating letters and Wilde’s friends Frank Harris and George Bernard Shaw told him he would be beaten in court. “You would be sure to lose [the case]” said Harris. “You haven’t a dog’s chance and the English despise the beaten”. But Wilde was determine to brazen it out and launched a libel action against the Marquess.

Queensbury was defended by Edward Carson, who would achieve celebrity as one of the strongest Unionist opponents of Irish Home Rule. Carson was a classmate of Wilde at Trinity College and Wilde remarked that “no doubt he will perform his tasks with all the added bitterness of an old friend”. Wilde played to the gallery with his witticisms but was badly hurt when cross-examined. Carson, armed with Queensbury’s letters, asked Wilde if he had ever kissed 16-year old Walter Grainger. Wilde replied he hadn’t because “he was extremely ugly”. Carson asked why ugliness should be an issue and Wilde stumbled saying “at times one says things flippantly when one ought to speak more seriously”.

Wilde lost his case for libel. The damning evidence that came to light in the trial proved sufficient for a prosecution. He was promptly arrested at the Cadogen Hotel, Brighton. Detectives had deliberately timed the arrest to be five minutes after the departure of the ferry to France, but Wilde failed to take the hint and stayed in England to meet his destiny. Wilde’s name was obscured on placards at the theatres showing the two plays. Eventually faced with “discordant remarks” from the gallery, both plays closed.

The press turned against Wilde. The Echo called for him to “go into silence and be heard no more”. The judge sentenced Wilde to two years hard imprisonment with hard labour for “acts of gross indecency”. He ended up in Reading Prison where he wrote a 50,000 word letter to Douglas known as “De Profundis” which he was not allowed to send. On his release he gave the letter to Robert Ross who gave a copy to Douglas though the latter would claim he never received it. The letter accused Douglas of thoughtless mistreatment, distracting Wilde from his art, and spending his money. It talked of his own “misplaced affection…through my own proverbial good nature and Celtic laziness”.

Here Wilde also wrote his best poetry: The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898). De Profundis and the Ballad showed that incarceration had, in the words of Colm Toibin “hurt him into a new style, direct and confessional, serious and emotional”. Wilde emerged from prison bankrupt, divorced and broken in spirit. He travelled in Europe where Douglas joined him. They split up again and Wilde moved into the Hôtel d'Alsace in Paris. He became ill in October 1900. His friend Robert Ross found a priest who baptised Wilde into the Catholic Church on his deathbed. He died of cerebral meningitis on 30 November. Douglas came to Paris for the funeral at Cimetière de Bagneux. Wilde’s body was later moved to Père Lachaise and Ross’s ashes joined him there fifty years later.

Here Wilde also wrote his best poetry: The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898). De Profundis and the Ballad showed that incarceration had, in the words of Colm Toibin “hurt him into a new style, direct and confessional, serious and emotional”. Wilde emerged from prison bankrupt, divorced and broken in spirit. He travelled in Europe where Douglas joined him. They split up again and Wilde moved into the Hôtel d'Alsace in Paris. He became ill in October 1900. His friend Robert Ross found a priest who baptised Wilde into the Catholic Church on his deathbed. He died of cerebral meningitis on 30 November. Douglas came to Paris for the funeral at Cimetière de Bagneux. Wilde’s body was later moved to Père Lachaise and Ross’s ashes joined him there fifty years later.

No comments:

Post a Comment