Tomorrow is the fifth anniversary of the sinking of Siev X. Siev X was an Indonesian fishing boat loaded with asylum seekers from Iraq and Afghanistan bound for the Australian Indian Ocean territory of Christmas Island. The boat sunk in international waters on 19 October 2001 causing the death of 353 people, the majority of which were women and children. Just 45 people survived, rescued by Indonesian fishing boats after spending over 19 hours in the water.

Tomorrow is the fifth anniversary of the sinking of Siev X. Siev X was an Indonesian fishing boat loaded with asylum seekers from Iraq and Afghanistan bound for the Australian Indian Ocean territory of Christmas Island. The boat sunk in international waters on 19 October 2001 causing the death of 353 people, the majority of which were women and children. Just 45 people survived, rescued by Indonesian fishing boats after spending over 19 hours in the water.The real name of the boat is unknown but Tony Kevin, an author and former Australian diplomat coined the name “Siev X” to stand for "Suspected Illegal Entry Vessel X” (X for Unknown). The day before the sinking, the boat left port in Bandar Lampung on the southern tip of the Indonesian island of Sumatra. It was a small boat barely measuring 80 square metres in size. It was a leaking hulk, unsafe and ill-equipped. Its cargo was humanity. The Egyptian people smuggler Mootaz Muhammad Hasan (aka Abu Quassey) had “chartered” the craft. On board were over 400 refugees prepared to put up with this hellish, cramped journey in order to gain access to a better life in Australia. They each paid Hasan $1,000 for the doubtful privilege. Ten people refused to board when they saw the condition of the craft but the remainder were forced on board at gunpoint by Indonesian officials.

The vessel stopped near the Karakatau islands where 24 passengers disembarked due to concerns about the boat’s seaworthiness. 397 passengers and crew remained onboard. 24 hours after leaving Bandar the two engines failed and the boat began to take on water. The boat listed violently to the side, capsized and sank within an hour. It was somewhere in the international waters of the Java Sea. The exact location is disputed but it is likely to be within Indonesia's zone of search and rescue responsibility but also inside the zone of Australia’s heavily patrolled border protection surveillance zone. The policing of this zone is known as Operation Relex. Operation Relex’s strategic aim was an extension of the Government’s new border protection policy: to prevent, in the first instance, the incursion of unauthorised vessels into Australian waters such that, ultimately, people smugglers and asylum seekers would be deterred from attempting to use Australia as a destination.

One of the few survivors, Hassan Jassem, from Basra in Southern Iraq, saw his wife and three children die. He and his family were in a room inside the boat when it started to sink. Many were sea sick. One of the boats two old engines wasn’t working and Hassan was trying to fix it. He watched in horror as the boat began to capsize. He saw his wife fall from the boat carrying their 20 day old baby. In the open water, Hassan searched desperately for his wife and family. “Every time I saw a child I could not differentiate between it and my children. My wife and children stayed under the boat - they never came out”, he said. He wasn’t wearing a lifejacket and was dragged under three times. “Anywhere I placed my arm, a drowned child or woman would emerge and lift my arm and the surviving women would cry more.”

Hassan was one of 44 survivors who survived the night and threat of sharks. They were rescued the following morning by an Indonesian fishing boat, the Indah Jaya Makmur. A 45th survivor was rescued about twelve hours later by another boat, the Surya Terang. He joined the other 44 in a holding centre 32km south of the Indonesian capital Jakarta. Eventually they were dispersed to many countries such as Finland, Sweden, Norway and Canada who afforded them permanent status. Just nine came to Australia where they were granted temporary protection visas.

The incident occurred during the highly-charged 2001 Australian federal election campaign. The terrorist attacks on New York were fresh in the memory. The election was dominated by the Tampa affair. MV Tampa was a Norwegian cargo boat which rescued stranded boatpeople in the Indian Ocean in August 2001. Australian authorities refused to allow to take them to the nearest landfall at Christmas Island. The Tampa captain asked Australia to send food and medical supplies urgently. Instead Australia sent five SAS commando troops onboard. The captain refused their request to move his ship back to international waters. The Norwegian government supported his decision. The Australian Navy eventually shipped the refugees to the Pacific island nation of Nauru. Prime Minister Howard’s strong stance won him great domestic support despite the international condemnation of Australia’s hard-hearted attitude.

The incident occurred during the highly-charged 2001 Australian federal election campaign. The terrorist attacks on New York were fresh in the memory. The election was dominated by the Tampa affair. MV Tampa was a Norwegian cargo boat which rescued stranded boatpeople in the Indian Ocean in August 2001. Australian authorities refused to allow to take them to the nearest landfall at Christmas Island. The Tampa captain asked Australia to send food and medical supplies urgently. Instead Australia sent five SAS commando troops onboard. The captain refused their request to move his ship back to international waters. The Norwegian government supported his decision. The Australian Navy eventually shipped the refugees to the Pacific island nation of Nauru. Prime Minister Howard’s strong stance won him great domestic support despite the international condemnation of Australia’s hard-hearted attitude.In 2002 the Australian senate investigated the incident as part of its inquiry into the Children Overboard Affair. The Children Overboard incident happened around the same time. John Howard had claimed incorrectly that refugees had deliberately thrown their children overboard so that they would be rescued by the Australian Navy. The inquiry looked at Australian culpability in the Siev X incident and whether it could have done more to help the victims. The committee noted that Australian information on Siev X “mirrored the general pattern of the intelligence in this area in that it was indefinite and in a state of flux.” They were aware in advance that the boat was small and overcrowded. They knew about Abu Quassey’s operation but had no idea where the boat was or even if it had left port. The Committee found no negligence or dereliction of duty but recommended “operational orders and mission tasking statements for all ADF operations, including those involving whole of government approaches, explicitly incorporate relevant international and domestic obligations”.

The man responsible for the sailing of Siev X is now in an Egyptian prison. Abu Quassey was found guilty by Cairo court of "causing death by mistake" and of "aiding and abetting the entry of aliens without effective travel documents." He got seven years for the crime but was reduced to five years on appeal. Defence lawyers argued that he was nothing more than an interpreter for the real mastermind of the people smuggling - Khaled Sherif, an Iraqi, who was arrested in Sweden and since extradited to Australia.

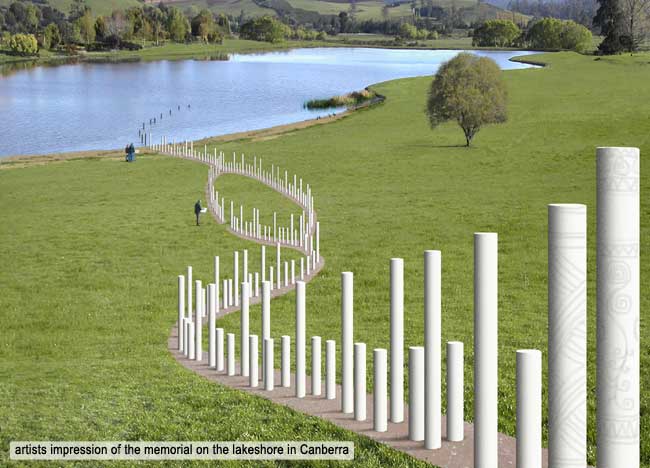

Plans to create a memorial for the Siev X victims have been thwarted by Australian government bureaucrats. On Sunday, hundres of people turned up to the shores of Canberra’s Lake Burley-Griffin to launch a permanent memorial of 353 white timber poles. However a month out from the launch date, organisers were told that it wouldn't be allowed. The National Capital Authority rejected the idea says following its mandatory guidelines saying 10 years must pass after an event, before a permanent memorial can be established. Event organiser Steve Biddulph told the ABC the decision was mean-spirited: “The Prime Minister is about to make a memorial to Steve Irwin. He made a memorial to the Bali bombing, 12 months after that happened and so there are many exceptions to the rule.” Instead the poles will be carried in a procession from the water's edge across a hillside, to show the planned design of a permanent memorial.

Plans to create a memorial for the Siev X victims have been thwarted by Australian government bureaucrats. On Sunday, hundres of people turned up to the shores of Canberra’s Lake Burley-Griffin to launch a permanent memorial of 353 white timber poles. However a month out from the launch date, organisers were told that it wouldn't be allowed. The National Capital Authority rejected the idea says following its mandatory guidelines saying 10 years must pass after an event, before a permanent memorial can be established. Event organiser Steve Biddulph told the ABC the decision was mean-spirited: “The Prime Minister is about to make a memorial to Steve Irwin. He made a memorial to the Bali bombing, 12 months after that happened and so there are many exceptions to the rule.” Instead the poles will be carried in a procession from the water's edge across a hillside, to show the planned design of a permanent memorial. The ABC interviewed Siev X activist Tony Kevin on the first anniversary of the sinking. The interviewer asked him whether Australians care about the issue given the strong support for border protection policy. He responded eloquently: “Our government agencies and unfortunately many of our media keep using these bland Orwellian phrases that conceal the reality which is people dying and drowning in the water….these are human tragedies in our society and we have to stop talking in abstractions about policy and start remembering the people.” His words remain unheeded in Canberra.

No comments:

Post a Comment