(Picture credit: snowsphere.com)

(Picture credit: snowsphere.com) Kashmir is one of the most beautiful places on Earth and also one of the most dangerous. Located in the shadows of Himalaya where three nuclear powers meet, parts of the ancient kingdom of Kashmir are claimed by all three. The provincial war of control between India and Pakistan erupted again this week. India’s Economic Times reporting that six members of the Islamabad-backed Jaish-e-Muhammad in a gun battle it described as between “terrorists” and “security forces”. Earlier this week. Pakistan’s Dawn also reported deaths in gun battles between the Indian military and “suspected Muslim militants” infiltrating the Line of Control that separates the two nations.

Violence in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir is nothing new; it has long been this way. Writing about Kashmir in 2002, Pakistani-born writer Tariq Ali describes the area as “trapped in [a] Neither-Nor predicament”. Home of the Nila Naga (the earliest Kashmiris) and ruled in turn by Shahs, Moghuls, Afghan and Sikhs it was acquired by the British East India company and was sold at profit to corrupt local warlords. It was split between India and Pakistan in 1947 and remains an open sore for both countries today. According to the Nilamata Purana, (the Nila Naga Myth of the Indigo Goddess) the name Kashmir is a corruption of words that mean ‘ a land desiccated from water’. But Kashmir has truly been desiccated more by blood than water.

Islam first arrived in Kashmir in the eight century. But the prophet’s armies that had carried all before them for the last hundred years were defeated here finding it impossible to penetrate the great mountains’ southern slopes. It would take another 500 years to establish Muslim rule. It occurred fortuitously; a Buddhist chief named Rinchana from a neighbouring area fell under the influence of a Sufi teacher and began to practice Islam. The Kashmir rulers’ Turkish missionary army gladly switched sides to their new co-religionist and then took over themselves when Rinchana died. The army’s leader Shah Mir established a dynasty that lasted to the twentieth century.

Though Shah Mir and his descendants did not entirely suppress the Indian religions, they did practice forced conversions. Slowly the population embraced Islam. By the time Zain-al-Abidin became Sultan of Kashmir in the late fifteenth century the population ratio of Muslims to non-Muslims was 85 to 15. It remains roughly that ratio in modern times. Zain-al-Abidin takes a lot of credit for this stabilisation. It was he who ended the practice of forced conversion and who rebuilt Hindu temples his father had destroyed. He visited Iran and Central Asia and brought back the arts of book-binding, wood-carving and the making of carpets and shawls. The word ‘shawl’ is Persian in origin but the costume would soon become the uniform of Kashmiri men.

Kashmiri fortunes declined after Zain-al-Abidin died. A succession of weak rulers hobbled by court intrigue meant that the kingdom was ripe for conquest. In 1583, Moghul emperor Akbar dispatched his favourite general to annex Kashmir. He took the province without bloodshed. The Moghuls were greeted with relief by a suffering populace unhappy with their own weak and corrupt government. The Kashmiri Shah struck a deal with the Moghuls handing over effective power but retaining the monarchy and the symbolic right to strike coins in his own image.

Angered Kashmiri nobles replaced the Shah with his son. Akbar was forced to send a large expeditionary force to crush Kashmiri resistance and take direct control. The Moghuls were enchanted by the physical beauty of their new conquest. Akbar’s son Jehangir wrote of Kashmir: “if on Earth there be a paradise of bliss, it is this”. Despite, or perhaps because of, this bliss, the Moghul empire went into decline, like all those before it. Kashmir fell under Afghan rule in 1752. Kabul held the reins of power until Sikh hero Maharaja Ranjit Singh extended his military triumphs from the Punjab by capturing the Kashmiri capital Srinagar.

Singh’s empire was secular and he abolished capital punishment. He is one of those rare figures of history revered in both India and Pakistan. But Kashmiri historians say his 27 year reign was disastrous. He closed the Srinagar mosques and imposed a hefty tax burden on the people. Mass poverty led to mass emigration. A Kashmiri Diaspora fled to the cities of the Punjab where they still live. Meanwhile new and stranger colonists were coming to claim Kashmir.

These new interlopers were businessmen. Britain followed the Dutch model and granted the East India Company semi-sovereign powers to look after imperial interests in the sub-continent. Based in Calcutta, they expanded rapidly and gained the whole of Bengal after the Battle of Plassey in 1757. British rule in India is conventionally described as having started with Plassey. The Company gradually wheedled and bribed their way through a succession of Indian rulers and rajahs. Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839 saw his kingdom plunge into disorder. The Company increased its military strength and broke diplomatic relations with the Sikhs. In 1846, the so-called first Anglo-Sikh war resulted in a decisive defeat for Singh’s descendents.

The resulting Treaty of Lahore signed away Kashmir to the British company. But the Brits immediately did a deal to sell most of the land to Gulab Singh for 75 lakh rupees (lakh is the Indian word for a 100,000). Gulab Singh was the Dogra ruler of neighbouring Jammu. The Dogras did as all previous rulers had done and squeezed every last rupee of tax out of Kashmir to make back the money they gave to the British. Meanwhile the Company rule was ended by the Indian Mutiny of 1857 bringing in direct rule. London did not directly interfere with Dogra rule of Kashmir and Jammu but a “British Resident” was the real power.

The twentieth century was late in arriving to the Himalayan valleys. Not until the 1920s did young Kashmiris educated abroad bring in the new ideas of nationalism, anti-colonialism and socialism. In 1924 Kashmir had its first strike; workers in a state-owned silk factory demanded a pay rise and the dismissal of a corrupt clerk. When the union leaders were arrested, the workers resisted and the Dogra Army put down the strike with the support of Britain. Sullen resistance to Dogra rule continued through the decade. Police stirred up a hornet’s nest by stopping Friday prayers in a Jammu mosque claiming the imam was preaching sedition. It triggered a wave of protests in Srinagar and elsewhere. A speaker described the Dogra as “a dynasty of blood-suckers” and was promptly arrested. His trial attracted thousands of protesters demanding to attend proceedings. Police retaliated killing 21 people. They also arrested several leading Kashmiri citizens including a man named Sheik Abdullah.

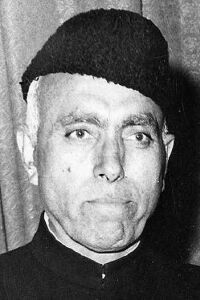

Abdullah's arrest would prove to be the founding moment of Kashmiri nationalism. After he was released, Abdullah set about creating a political movement. The All-Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference was founded in Srinagar in 1932. Despite the name, the AJK MC was open to Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Although the Hindus were a minority, Abdullah knew it would be stupid to offend the Pandits, upper class Brahmins whom Britain used to administrate the province.

Abdullah's arrest would prove to be the founding moment of Kashmiri nationalism. After he was released, Abdullah set about creating a political movement. The All-Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference was founded in Srinagar in 1932. Despite the name, the AJK MC was open to Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Although the Hindus were a minority, Abdullah knew it would be stupid to offend the Pandits, upper class Brahmins whom Britain used to administrate the province.To demonstrate his secular credentials, Abdullah invited the nationalist Indian leader Nehru to Kashmir. Nehru brought with him Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the man known as “the Frontier Gandhi”. Khan was an eloquent Muslim equivalent of Gandhi. Together, the three men formed a potent partnership. Abdullah promised liberation from the hated Dogra. Nehru preached the struggle against the British Empire and Khan spoke of the need to throw fear to the wind. “You who live in the valley”, he told his audience, “must learn to scale the highest peaks”.

The bond between the Nehru and Abdullah would prove crucial during the independence struggle. In any case, few politicians in the 1930s believed the subcontinent would be divided along religious lines. Even the most ardent Muslim separatist would have been happy with regional autonomy along federal lines. But old certainties were shattered by World War II. The British Empire including India was suddenly at war with Germany. Nehru was furious he was not consulted in the decision. His Congress party split with Nehru and Gandhi reluctantly supporting Britain while hardliners such as Subhas Chandra Bose argued for an alliance with Japan. The fall of Singapore in 1942 left Indians convinced the Japanese would take their country via Bengal. Congress threatened to switch sides.

A desperate Britain offered a carrot of a “blank cheque” to Nehru not desert the cause. Gandhi wondered aloud “what is the point of a blank cheque from a bank that is already failing?” As a result the Congress launched the Quit India movement. As a result of the civil disobedience its entire leadership including Gandhi and Nehru were thrown in jail. Meanwhile Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League backed the war effort. Uneasy with Gandhi’s use of Hindu imagery, Jinnah left the Congress in the 1930s to set up his own Muslim organisation. Pakistan was his reward for war loyalty.

As the war ended in 1945, Nehru and Khan revisited Abdullah to find the Muslim-Hindu divide had started to stoke up in Kashmir. Just as in the divided provinces of Punjab and Bengal, violence erupted between rival factions. In the NWFP, Muslim League forces defeated Khan’s anti-partition troops. Khan lived until the 1980s but would spend most of his remaining days in a Pakistani prison. Khan’s defeat rocked Abdullah whose power in Kashmir grew as the British began to withdraw. Nonetheless the Dogra still held official power. In constitutional terms Kashmir was a “princely state” whose maharaja held the ultimate right to choose either to confederate with India or Pakistan.

Other Muslim ruled princely states such as Hyderabad and Junagadh chose India. But they both had Hindu majority populations. Kashmir was different. Jinnah negotiated directly with the Dogra maharaja to join Pakistan. Abdullah was outraged he was not involved. The maharajah baulked and Kashmir’s status remained unresolved when midnight struck on 14 August 1947 creating the new states of Pakistan and India. A line of control in Kashmir was established between the two countries. Both sides held armies commanded by British officers. Last British Viceroy Mountbatten made it clear to Jinnah that he would not tolerate a violent take-over of Kashmir.

Nevertheless Jinnah secretly plotted to take over the disputed Muslim province. Meanwhile Kashmir’s maharaja was now secretly plotting with the Congress Party. Once the British found out about Pakistan’s invasion plans they told Nehru who pressurised the maharaja to join India using the invasion as a pretext. Mountbatten ordered Indian army units to prepare to airlift to Srinagar. Once Pakistan invaded, the maharaja’s regime quickly collapsed. The undisciplined Pakistani army raped, looted and pillaged along the way assaulting Muslims and Hindus alike. Indian troops landed outside Srinagar where they waited for reinforcements. The Pakistanis invaded the city and pillaged shops and bazaars but overlooked the airport which was occupied by the Indian Army. The exiled maharaja signed the accession papers to India and demanded help to repel the invasion.

Matters were at a stand-off; it would all now depend on which side Sheik Abdullah supported. He regarded Jinnah’s Muslim League as a reactionary organisation who would prevent the needed social and political reforms in Kashmir. In 1947 he attended another rally with Nehru at his side. Abdullah publicly backed the Indian presence provided Kashmiris were allowed to determine their own future. What Abdullah wanted was an independent Kashmir but the 1947 wars ended that hope.

According to article 370 of the constitution, India recognised Kashmir’s “special status” but nothing more. In 1948 a realistic Abdullah backed “provisional accession” keeping Kashmir autonomous leaving India responsible for defence, foreign affairs and communications. Hardline Indian nationalists baulked at this special status. Eventually Nehru authorised a coup in 1953 to dismiss his old friend Abdullah. The unrest that followed made Kashmiris suspicious of Indian rule. Abdullah remained a thorn in India’s side.

After being released from prison, he flew to the Pakistani controlled side of Kashmir where a large crowd cheered him. He was arrested again after meeting with Chinese Premier Zhou En Lai. Meanwhile China launched its own assault on northern Kashmir resulting in a new administration of the region called Aksai Chin, which survives today. Encouraged by the disturbances Pakistan launched another assault on Kashmir in 1965 hoping to spark an uprising. India responded by attacking Lahore. Eventually Washington asked Moscow to put pressure on India to end the war.

After being released from prison, he flew to the Pakistani controlled side of Kashmir where a large crowd cheered him. He was arrested again after meeting with Chinese Premier Zhou En Lai. Meanwhile China launched its own assault on northern Kashmir resulting in a new administration of the region called Aksai Chin, which survives today. Encouraged by the disturbances Pakistan launched another assault on Kashmir in 1965 hoping to spark an uprising. India responded by attacking Lahore. Eventually Washington asked Moscow to put pressure on India to end the war. Devastated by defeat in Bangladesh new Pakistani Prime Minister Ali Bhutto sued for peace with India. In 1972 he agreed to the status quo in Kashmir and got back 90,000 POWs captured after the fall of Dhaka in what had been East Pakistan. Abdullah made his peace with Delhi and was appointed Chief Minister of Kashmir by Indira Gandhi in 1977. When Bhutto was executed two years later, Pakistan’s last hope of peacefully taking Kashmir disappeared. Abdullah died in 1983, a tired and broken man resigned to Kashmir’s fate. The end of the cold war escalated the war between the two sides as the US and USSR lost interest in this Himalayan pawn.

The border and the Line of Control separating Indian and Pakistani Kashmir passes through some of the planet’s most difficult terrain. The continual low-level sniping between the two sides has led to a significant loss of human rights in Kashmir. A Medecins Sans Frontieres study in 2005 found that Kashmiri women are among the worst sufferers of sexual violence in the world. Since the violence escalated in 1989, sexual violence has been routinely perpetrated on Kashmiri women, with over one in ten respondents saying they were victims of sexual abuse.

Many people now see independence as the only way out of Kashmir’s nightmare. In 2001 the former Chief Justice of Delhi High Court Justice Rajinder Sachar said restoring pre-1953 special status to Jammu and Kashmir was the only solution to the problem. Sachar called both Indian and Pakistani governments hypocrites and said armed conflicts could not solve this complex issue and only political dialogue could reach a solution. ``When France and Germany which have a bitter history of conflicts can become good friends and work towards better future, “ he said, “then the same is possible in case of India and Pakistan."

5 comments:

I've seen

'Carry On Up The Khyber" ...

it wasn't like that at all.

Recently I guugled something, and one of the categories at the bottom of the results page was 'infidel blogs' - be afraid.

But perhaps not afraid of Sikhs in Melbourne: yesterday in the pouring rain I survived a car crash across multiple oncoming freeway lanes .. and the ONLY helpful people were turbanned youths I would previously have not perceived in a positive way.

One man's Terrorist, is another man's Security Force, and that reminds me of my Himalayan blogger pal Donkey Blog.

A melbourne guy who works in Tibet and its neighbours,

AND CAN DESCRIBE A MOUND OF STREET-CORNER GOATSHEADS,

IN A WAY WHICH UNDERMINES EVERYTHING THEIR TOURISM BOARD CAN RETALIATE WITH.

oh I'm too lazy and cold to fix that: peace and love, B

Here's a clip from The Donkey blogger

"in the UN, it seems you have to wear an Armani suit to work every day. So right from the starter’s gun, every UN representative in the place is looking sharper than Sweeny’s razor and smells like the ground floor of a flashy department store.

By contrast, all the journos in attendance are haggard, chain-smoking, hard drinking types whose eyes (perhaps an effect of reporting from too many armed conflicts) don’t seem to be able to remain still for more than a quarter of a second. These men and women party every night like there’s no tomorrow, ‘cause for some of them that’s probably true … but bearing in mind that they turn up to these meetings each “tomorrow” morning, they rarely seem to have much to contribute; they are generally as unwashed and unironed as their clothes. ...."

its worth your time to visit him, and now i have to turn on Barry Cassidys Insiders for the cartoon segment.

Hi,

The very first picture in this article (the one of the Skikaras in Dal Lake is copyrighted property of SnowSphere.com).

Please either add a credit link to SnowSphere.com or remove it from your website.

Thanks

Thank you for adding the credit - it's appreciated.

Post a Comment