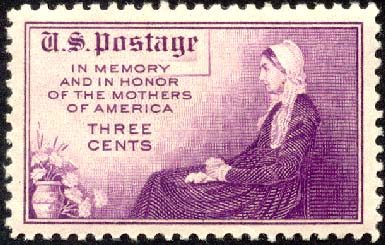

The work colloquially known as “Whistler’s Mother” is among those few famous paintings such as the Mona Lisa and American Gothic which have transcended art and entered popular culture. The painting was in the news last week, as it always is at this time of year, in celebration of Mothers Day. The Musée d'Orsay painting featured on the first US stamp to commemorate the day in 1934. The woman that did most to make the day a celebration – Anna Jarvis (ironically never a mother herself) – was furious that the US postal service chose the Whistler painting to honour the day without consulting her.

The work colloquially known as “Whistler’s Mother” is among those few famous paintings such as the Mona Lisa and American Gothic which have transcended art and entered popular culture. The painting was in the news last week, as it always is at this time of year, in celebration of Mothers Day. The Musée d'Orsay painting featured on the first US stamp to commemorate the day in 1934. The woman that did most to make the day a celebration – Anna Jarvis (ironically never a mother herself) – was furious that the US postal service chose the Whistler painting to honour the day without consulting her.But while Jarvis may have been unhappy, mainstream America was not. There was little doubt in most people’s eyes that the austere portrait of Anna McNeill Whistler by her son James was the quintessential picture of motherhood. What is less well known is the controversy the painting stirred up when it was painted in 1871. And its apparent conservative nature seems a bizarrely uncharacteristic work. Whistler was of one of the 19th century’s most unorthodox painters and was a leading proponent of the bohemian credo “l’art pour l’art” (art for art’s sake) that divorces art from any didactic, moral or utilitarian function.

Much of the controversy raged over the paintings name. While it is commonly now known as “Whistler’s Mother”, the actual title of the painting is “Arrangement in Grey and Black”. When Whistler tried to display the painting in 1872 at London’s 104th Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Art, the art world was horrified. The Victorian guardians of the Royal Academy could not cope with a painting of a person, especially a mother, described as a mere “arrangement”. Threatened with expulsion from the exhibition, Whistler compromised and added a subtitle: “The Artist’s Mother”.

This most American icon has never lived in the US, though it has toured several times. Its life mirrored that of its American creator who spent most of his life in Europe. James Abbott McNeill Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts in 1834, the son of a railway engineer. When his father, George Washington Whistler, moved to St Petersburg to work on the Russian railway, his son enrolled at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts where he learned French. He finished his education at West Point and worked briefly as a coastal surveyor etching maps. But he found American society too restrictive for his worldly sensibilities. He moved to Paris where he finished his art education at the Ecole Impériale et Spéciale de Dessin, before entering the Académie Gleyre.

Whistler was a flamboyant dandyish presence in Paris wearing a straw hat, a white suit, highly polished black patent leather shoes and a monocle. Here he also gained an appreciation of Asian (especially Japanese) art and mixed with prominent artists such as Courbet, Manet and Degas. The circles in which he moved can be gauged from Fantin-Latour's Homage to Delacroix, in which Whistler is portrayed alongside Baudelaire, Manet, and others. Camille Pisarro acknowledged the young man’s talent saying "this American is a great artist.”

But not everyone in Parisian society recognised this immediately. Whistler achieved international notoriety when Symphony No. 1, The White Girl was rejected at both the Royal Academy and the Salon, but it became a major attraction at the famous Salon des Refusés (“exhibition of rejects”) in 1863. The title of his painting also alluded to Whistler’s lifelong habit of calling painting by musical titles such as symphonies, nocturnes and arrangements. Whistler’s explanation was that “as music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, the subject matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or colour."

But not everyone in Parisian society recognised this immediately. Whistler achieved international notoriety when Symphony No. 1, The White Girl was rejected at both the Royal Academy and the Salon, but it became a major attraction at the famous Salon des Refusés (“exhibition of rejects”) in 1863. The title of his painting also alluded to Whistler’s lifelong habit of calling painting by musical titles such as symphonies, nocturnes and arrangements. Whistler’s explanation was that “as music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, the subject matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or colour."Whistler moved to London in 1859 where he continued his bohemian lifestyle and prolific painting. His etchings of the Thames won him great acclaim. He flouted Victorian conventions and lived with his model Joanna Heffernan. His life was turned upside down in 1863 when he received a letter from his mother Anna in civil war-ravaged America saying she was moving to London to be with her son. James turned his ramshackle apartment upside down to make it respectable and evicted Joanna. Anna would now rule the entire household except for her son’s studio.

Anna did not always approve of her son's relaxed lifestyle, but she took an active interest in his painting. Her appearance in her son’s most famous painting was a happy accident. His original model was ill and unable to show up so James demanded that his mother pose for him. The original plan was for her to stand, but her aged body was unable to cope so they decided to use a chair instead. Whistler’s inspiration was to face his mother away from the viewer’s gaze. In his startlingly bare “arrangement”, Whistler succeeded in conveying his mother’s strong Protestant character in the sombre pose, expression and colouring.

The picture proved to be an immediate sensation at the London exhibition. Viewers might have been shocked at this artist’s daring depiction of his mother as an arrangement but no one could doubt the painting’s power. Whistler kept the painting for several years before selling it to the French state. It was displayed in Paris' Musée du Luxembourg in 1891 and was exhibited in several museums until it found a permanent home in the new Musée d'Orsay in 1986.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that the picture took off as an icon for motherhood, parental affection, and "family values". The picture toured America in 1932 during the height of the depression. Anna McNeill’s Whistler’s stern visage struck a chord with ordinary Americans and her values seemed in tune with the times. Within two years, its status as a maternal symbol saw it recognised in the stamp (though some were outraged at the bowdlerised addition of the bowl of flowers absent from the painting itself.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that the picture took off as an icon for motherhood, parental affection, and "family values". The picture toured America in 1932 during the height of the depression. Anna McNeill’s Whistler’s stern visage struck a chord with ordinary Americans and her values seemed in tune with the times. Within two years, its status as a maternal symbol saw it recognised in the stamp (though some were outraged at the bowdlerised addition of the bowl of flowers absent from the painting itself.In modern times, the painting retains a power even if poor old Anna herself has been ridiculed in countless modern situationist adaptations. While her stern visage is seriously dated and no longer an appropriate symbol for all that is good in motherhood, the stark power of Whistler’s art still shines through and is as relevant as ever. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Whistler was not interested in telling a story or in idealising the subjects in his paintings. He considered subject matter less important than colour and composition, and focused on creating a mood in his work. The original title now needs to be reclaimed: it is not Whistler’s mother that is important, it is the arrangement in grey and black.

No comments:

Post a Comment