The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) has protested the

jailing of an Algerian newspaper editor for criticising the government. On Monday, a court handed out a six month defamation sentence to Dhif Talal, correspondent for the Arabic-language newspaper Al Fadjr in the north-central city of Djelfa. Talal was convicted for an article he wrote exposing poor administration practices in the Department of Agriculture. Another journalist faces charges next month for an article he wrote about the Education Department. The IFJ General Secretary has called on the government to “make a commitment to press freedom and to allow the media to work independently without fear of reprisals”.

Algeria has slipped quietly under the radar of world trouble spots since the 1990s civil war that followed the overthrow of its elected Islamist government. Yet the Islamic opposition have not gone away and anger over the 1992 coup remains deep. Pan Arabic elements are now infiltrating the local opposition. Last month, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika survived an

assassination attempt that killed 22 people in a suicide bombing in the north-eastern city of Basna. Al Qa’ida’s Maghreb offshoot have claimed responsibility for this attack and also a bomb attack on a naval barracks in September 2006 that killed 32 people.

Outside interference is now threatening a fragile peace in a country that has long been at war with itself. In the aftermath of the 1992 coup, both government and opposition death squads routinely killed its enemies as well as innocent civilians. 150,000 died in the years that followed. The economy went into a tailspin and there were massive food shortages.

President Bouteflika, elected in 1999, is credited with turning Algeria around. He negotiated reconciliation with Islamist fighters in 2005 as well as pacifying the Berber minority.

Bouteflika like all Algerian leaders before him has the

support of the French President, now Nicolas Sarkozy. France occupied Algeria for 132 years and continues to be a hugely influential actor in Algerian events. Algeria was one of Europe’s earliest colonial incursions in Africa and one of its deepest in impact. Algeria was incorporated into metropolitan France and one million “colons” (French Algerians) crossed the Mediterranean to administrate a country of nine million Muslims. Algeria has long been an attractive proposition for invaders such as the Phoenicians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Arabs and Ottomans. The latter two inculcated the practice of Islam. But the French brought the iron rule of European law.

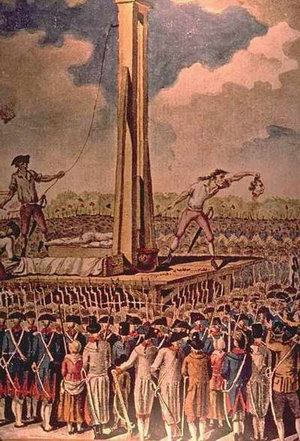

In 1830, French

King Charles X dispatched a 37,000 strong army under the pretext of suppressing Algerian piracy and easily deposed of the Turkish Dey of Algiers. The tone of the invasion was set on the first day when the French looted 100 million francs from the Kasbah. The French immediately encouraged colonial settlement. By 1841 37,000 settlers had appropriated Algerian land and institutionalised their rule with routine violence and usurpation of all the country’s most productive property. The initial war of occupation would last 18 years and end with the capture of the eastern city of Constantine.

France established a two-class apartheid system where Europeans were “supercitizens” and Algerians were the “servile class”. The Grand Mosque of Algiers became the Catholic cathedral of Saint-Phillipe. Algerian anger at French occupation flared up again in 1870 after the Prussian defeat of France. A rebellion centred in the Berber region of Kabyle took over a year to suppress. In 1881 the French enacted the Code de l’Indigenat, a

Native Code statute which had 41 laws that applied only to Algerians. The Code made it an offence to criticise the French Government, travel without a pass, teach people without permission, and gather in groups of more than 20.

Algerian nationalism rose in the period after World War I. A group of French-educated Muslim intellectuals founded the Young Algerian Movement in the 1920s. The first political party was the Algerian People’s Party (PPA) founded in 1937 with a motto of “neither assimilation nor separation but emancipation”. Nationalists took heart from the Nazi defeat of France and then the Anglo-American liberation of Algeria in 1942. After the war several pro-independence groups coalesced into the

National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale - FLN).

While the French were divesting their colonies worldwide, there was more resistance, especially among the million colons, to the independence of Algeria. In theory Algeria was part of France itself. The FLN lost patience with French inaction and launched the Algerian war of independence in 1954. One of the great 20th century liberation struggles began in the early morning hours of the first of November 1, when

FLN maquisards (guerrilla soldiers or “terrorists” to the French) launched attacks in various parts of the country against military installations, police posts, warehouses, communications facilities, and public utilities. The maquisards operated with a great deal of independence as FLN’s leadership, including future president Ahmed Ben Bella, was in exile in Tunisia and Morocco.

The war would last for the rest of the decade. The FLN supported the guerrillas with an army of 40,000 soldiers along the borders which used hit-and-run tactics to harass the French. It was a bloody war. Estimates of deaths on the Algerian side range from 200,000 to a million. While the French mostly prevailed on the battlefield, they lost on the streets back home. By 1962, the war had killed 25,000 soldiers and 3,000 colons and had put France on verge of bankruptcy. In 1958 the war brought down the

Fourth Republic and Charles de Gaulle was brought out of retirement to fix the mess.

In 1962 De Gaulle

negotiated the Evian agreements with the FLN. France withdrew from Algeria in exchange for military bases and oil and gas concessions in newly discovered fields in the Sahara. The last sorry chapter of the war was fought by a hardcore contingent of colon militants who formed the Secret Army Organisation (OAS) and killed 3,000 Muslim civilians in a campaign of terror aimed at destabilising the truce. Almost all of the one million colons fled Algeria within weeks of the new nation’s independence.

After the French left, the exiled faction of the FLN led by Ben Bella seized control.

Ahmed Ben Bella had spent much of the war in a French prison. He quickly consolidated power in 1962. He declared the FLN the only legal party and co-opted trade unions and other organisations into the party. But Ben Bella promoted a personality cult and that, allied with erratic policy shifts, caused opposition to grow against him. He was deposed in a coup in 1965 by an army which preferred consensus rule to Ben Bella’s authoritarianism.

His replacement was

Houari Boumedienne, his former deputy. Boumedienne completed the centralisation of state control and elimination of independent institutions. The military was firmly established as the final arbiter of disputes within the FLN. Boumedienne steered Algeria outside both the US’s and the USSR’s sphere of influence. His unexpected death in 1979 brought Chadli Benjedid to power.

Unlike the previous two leaders

Benjedid was only a minor figure in the war of independence. However he was a competent administrator and continued Boumedienne centrist policies. But the first cracks were appearing in Algeria’s apparent mono-culture. Riots broke out at the University of Algiers over the predominance of French over Arabic in classes. The non-Arab speaking Berbers in Kabyle then protested against the growing Arabism. Thirdly, there rose an Islamic opposition initially dedicated to the imposition of strong Sharia laws. The FLN were also deeply worried by the success of the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

Benjedid dealt with this challenge by instituting a

Family Code in 1984 which curtailed the rights of Muslim women. They could not marry non-Muslims, could not seek a divorce, and needed permission from husband or eldest son to work or travel. But while this move pacified the Islamists, Algeria continued to struggle economically, stifled by bureaucratic centralism and rampant corruption. The collapse of oil prices in the mid-1980s destroyed Algeria’s foreign income and left most of the country in poverty while the elite of the FLN lined their pockets.

Violence against the regime accelerated through the rest of the decade. By September 1988, labour unrest had spread around Algiers’ industrial belt and into the public service companies of the capital. The government cracked down brutally and massacred over a thousand people at a demonstration. The opposition redoubled their efforts and a panicked Benjedid was forced into a series of reforms. He liberalised the press and legalised political parties. By 1991, over 50 new parties were formed including the largest of all, the

Islamic Salvation Front (FIS).

Initially created as a network of informal mosque groups (the only independent groups to avoid takeover by the FLN), they first stood for office in the 1990 municipal elections. They stunned the FLN by taking 54 percent of the vote, almost double the FLN total of 28. The FIS took control of 850 of Algeria’s 1,500 municipal councils. The FLN hoped the newcomers would blunder in their new power role and be a spent force by the time of the national elections. They also hoped the people would quickly find the FIS planned social restrictions distasteful. The FLN were wrong on both counts. The hated French support for the government didn’t help their cause either. In December 1991, Algeria went to the polls and the FIS again

trounced the FLN in a violence-free election.

The result horrified the FLN elites who had ruled the country since independence. They quickly moved to secure power. In January 1992 Benjedid resigned and the army High Security Council announced the

formation of a collective presidency known as the High State Council (HCS). The first act of the HCS was to declare the December election void. They also cancelled runoff elections scheduled for February. Their argument was that FIS was a sham-democratic movement which had theocratic ends. If it gained power, it would not surrender it, their description of the FIS was “one man, one vote, one time”. The FIS was stripped of its victory, declared illegal and its leaders jailed.

The announcement sparked war. The

GIA (Armed Islamic Group) was a military offshoot of the FIS whose core members were known as “Afghanis” because many of them fought with the Mujahideen against the Soviets in the 1980s. In 1993 the GIA issued a challenge to the 100,000 foreigners in Algeria – leave or die. By the end of 1994, foreigners were frequent victims of the growing war. Women who failed to wear the hijab were also targeted by the militants.

The HCS crucially gained the support of France which was desperately worried by a mass refugee movement in the wake of an Islamist victory. The GIA took the war to France. In 1994, they bombed the Paris Metro, attacked the train network and hijacked an Air France jet. Meanwhile Algeria had descended into

civil war which immersed the country for the rest of the 1990s. Estimates of total deaths range from 70,000 to 200,000.

Elected president in 1999, Abdelaziz Bouteflika was credited with ending the war. He released thousands of Muslim militants from jail and won support for a civil concord to offer amnesty to armed militants. Many of the rebels accepted and the violence declined. But Bouteflika has been a strong supporter of the US-led “war on terror” and that has led to stronger imternal Islamist opposition. Al Qaeda have now formed an

alliance with the Salafist Group (GSPC). The GSPC is itself an offshoot of the GIA. In 2005, the GSPC singled out France as its "enemy number one" and issued a call for action against the country.

While Algeria deals with the international threat of GSPC, it has closed down criticism within its borders. IFJ General Secretary

Aidan White says Algeria has been using its criminal law to silence critical voices. “Journalists continue to be victims of this repressive tactic,” White said. “We are calling on the government to make a commitment to press freedom and to allow media to work independently without fear of reprisals.”

I saw a movie last night where the main character is one of the most reviled archetypes in Australia: a people smuggler. The film was Aki Kaurismaki’s Le Havre and the character was Marcel Marx, a Frenchman who aides an African boy on the run from immigration authorities.

I saw a movie last night where the main character is one of the most reviled archetypes in Australia: a people smuggler. The film was Aki Kaurismaki’s Le Havre and the character was Marcel Marx, a Frenchman who aides an African boy on the run from immigration authorities.