Pro-whaling countries won a major victory this week when the International Whaling Commission (IWC) declared to return to its “original mission as a body to regulate whaling”.

Pro-whaling countries won a major victory this week when the International Whaling Commission (IWC) declared to return to its “original mission as a body to regulate whaling”.The controversial and tight vote (passed by 33 votes to 32) does not mean an immediate return to commercial whaling; it needs a three-quarters majority for that. But is it a definite declaration of intent that calls for the eventual lift of the twenty-year global suspension on whaling. The vote was held in its annual meeting in the tiny Caribbean island nation of St Kitts Nevis.

The IWC also voted on other matters such as increasing its numbers from 66 to 70. There are some odd member countries. The group of 70 includes the Marshall Islands and the meeting hosts St Kitts Nevis neither of which has a whaling tradition. It could be argued they have vested interests as coastal nations. Odder still are Mali and Mongolia, neither of which has a coastline at all. It would be safe to say that their delegates enjoyed a few days in the Caribbean. Canada is oddest of all as it is not a member. It conducts modest whaling outside the sanctions of the IWC. New Zealand has criticised Japan, the leading pro-whaler still working within the commission, for vote-buying among the smaller members. But there are two steady blocs within the commission. Voting in the conference on all other issues were close. Barely two votes separated any issue and nothing carried unanimously. The closeness is reflected in the organisation; The US is chair and Japan is vice chair.

New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark accused Japan of “driving a wedge through the Pacific” by spending big among the small islands. The Solomon Islands voted for Japan and their opposition wants Fisheries Minister Nollen Leni sacked for defying a cabinet decision to abstain. French Polynesia meanwhile claims its vote with the anti-whalers could ensure they have whaling tourist dollars thrown at them instead.

Japan placed a peculiar item on the agenda called “normalising the IWC” which was voted down because no-one could agree what normalising meant. Japan want to make it normal because, to use their words, it is dysfunctional. Their argument is that the IWC is too busy being a stage for conflicts to have time to be a resource management organisation. They, and their allies believe that there is a place to allow more sustainable whaling than is currently allowed. Japan has a permit to kill the smaller minke and fin whales (aka lesser rorquals) for research. Iceland has something similar. Aboriginals in Alaska and the Indonesian island of Lembata are allowed to hunt for cultural reasons; they get a “subsistence allowance”.

Iceland has cultural and aboriginal reasons too, It was one of the last big islands to be inhabited by humans. Norwegians arrived there in the 9th century and whaling quickly became a crucial source of industry and rare source of food on the barren island. The age and importance is reflected in the Icelandic word “hvalreki” which means both "beached whale" and "jackpot".

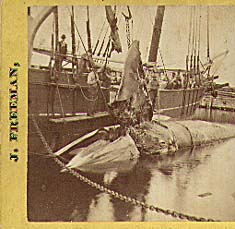

Harpooning of whales by hand began in Japan 800 hundred years ago. The Basques dominated the field in Europe. But it was the Americans who turned it into mass production from their base in Nantucket, Massachusetts. Between the 1812 War and the US civil war, Nantucket was by far the biggest whaling town in the world. Inevitably it overfished and turned Moby Dick into a white ghost. The discovery of petroleum drove the price of whale oil down and Nantucket died too.

Harpooning of whales by hand began in Japan 800 hundred years ago. The Basques dominated the field in Europe. But it was the Americans who turned it into mass production from their base in Nantucket, Massachusetts. Between the 1812 War and the US civil war, Nantucket was by far the biggest whaling town in the world. Inevitably it overfished and turned Moby Dick into a white ghost. The discovery of petroleum drove the price of whale oil down and Nantucket died too. Opponents argue the we will have hit the hvalreki for the last time unless whaling is banned entirely. In 1994, Australia legalised their theoretical 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around the Australian Antarctic Territory. One of the rationales used was that it would thwart the Japanese whaling program. However, Antarctic territories are not generally recognized internationally and Australia did not make an issue out of it. The Treaty of the Antarctic says that "Antarctica shall continue forever to be used exclusively for peaceful purposes". Australia knew that they couldn't be seen as the first to break ranks in that powerful group. The treaty will come under increasing strain anyway as access to resources becomes increasingly thin this century.

The strain on whales remains here and now. No human knows what they think of it all. They still sing but might be mourning their luck that our factory ships are now bigger than they are. Time will remember whether they are a "sustainable resource" or not.

No comments:

Post a Comment