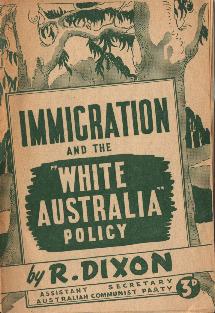

The White Australia Policy was an Australia commonwealth law between 1901 and 1973. Though it has been off the books now for over thirty years it still has the ability to generate controversy. Keith Windschuttle, the leading player on the right in the Australian history wars debate, wrote what was a brilliant history called “The White Australia Policy” in 2004.

The White Australia Policy was an Australia commonwealth law between 1901 and 1973. Though it has been off the books now for over thirty years it still has the ability to generate controversy. Keith Windschuttle, the leading player on the right in the Australian history wars debate, wrote what was a brilliant history called “The White Australia Policy” in 2004.The problem is that this subject is so politicised, it is sometimes very difficult to see the history "would" from the history "truth". Windschuttle impressively presents his information with an avalanche of footnotes and a forest of references in a document that is never less than excellent scholarship.

But the Age critic Marilyn Lake gives the book an awful caning in her review. She says the book is a deeply political work, "combative in tone, often contemptuous of other people's work, passionate and polemical in argument”.

And she should know, being one of the victims of Windschuttle’s contempt in the book. Marilyn Lake is a historiographer at Melbourne’s La Trobe University and is the biographer of civil rights activist Faith Bandler. Bandler wrote a book called Wacvie in 1977 purporting to be the story of her father Wacvie Mussingkon, a Kanaka who was kidnapped into working on a Queensland sugar plantation. Bandler’s tale is about a form of slavery that existed in Australia in the late 19th century. The process was called by a poetic name ‘blackbirding’. In 1883 Wacvie was taken from his home of Ambrym, a volcanic island off the coast of what was then known as the New Hebrides and is now called Vanuatu. Enter into the story another historian Peter Corris. He complicates matters by describing Bandler’s story of her father’s kidnap as a fabrication. Wacvie may be about her father, but Bandler’s work was fiction. By 1880, the Ambrym trade with Queensland was legal and the islanders were making a lot of money from indentured labour. Corris’s exposure hurt Bandler. Bandler complained to Lake that she thought she was being patronised. Lake justifies Wacvie as a work of history because ‘stories about the past do not all speak the same language or follow the same rules’. But Keith Windschuttle’s sees it as ‘inventing facts to mislead her readers’.

As well as dispelling myths about blackbirders, Windschuttle is also applying a very different attribution to the White Australia Policy itself. The six Australian colonies that came together in 1901 are traditionally have said to have instigated the policy out of fear of invasion and the concern for the purity of the white race. The White Australia Policy of that year was the federal government’s first substantial legislation. Richard White described how 19th century Australians saw themselves as similar to the South African ‘uitlanders’, the white English who tried to bring order to the decaying Boer regime. They were the King’s men alright but brought a new zealous outback version of imperialism. Great Britain itself could not condone this action, they had a multi-racial empire to maintain. But the country they created as a dump for prisoners was now trying its damnest to be British in a part of the world where they were in a severe minority. Where Windschuttle disagrees with accepted wisdom on the policy is in understanding its cultural causes.

As well as dispelling myths about blackbirders, Windschuttle is also applying a very different attribution to the White Australia Policy itself. The six Australian colonies that came together in 1901 are traditionally have said to have instigated the policy out of fear of invasion and the concern for the purity of the white race. The White Australia Policy of that year was the federal government’s first substantial legislation. Richard White described how 19th century Australians saw themselves as similar to the South African ‘uitlanders’, the white English who tried to bring order to the decaying Boer regime. They were the King’s men alright but brought a new zealous outback version of imperialism. Great Britain itself could not condone this action, they had a multi-racial empire to maintain. But the country they created as a dump for prisoners was now trying its damnest to be British in a part of the world where they were in a severe minority. Where Windschuttle disagrees with accepted wisdom on the policy is in understanding its cultural causes.Charles Pearson’s "National Life and Character" was a hugely influential book in 1893. His book was a forecast to a time when the whites would be overrun by other races. It gave rise to the fear of the Yellow Peril. It gave Theodore Roosevelt the excuse to go on his wars of American expansion. Pearson was British but emigrated to Australia in 1871. He was a close friend and major influence on Alfred Deakin, Australia’s second prime minister and most influential post-commonwealth politician. Darwin’s name was dragged into the argument as a spurious re-reading of his theories led to Social Darwinism. Darwin’s scientific views were twisted into a social context by the Prussian academic Heinrich Von Treitschke. Though Von Treitschke was fervently anti-British some of his ideas on race translated well across the North Sea and thence to its white colonies.

Windschuttle rejects the notion that Social Darwinism, so admired by Hitler, was the cause of the Policy. Instead, he ascribes the major influence to the Scottish Enlightenment. Scotland was governed from Westminster since the Act of Union of 1707 and the Scots spent much of the 18th century wondering whether the country would “become prosperous like England, or would it descend into dependent pauperism like Ireland?” The enlightenment lasted roughly 50 years from about 1740. Scotland produced a stellar list of intellectuals in this era. It was led by David Hume, Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson. The Scottish view was based on observation of their own highlanders and it proposed that human society had developed in four stages: hunting, pastoral, agricultural and commercial. Each society was somewhere along this scale. The Scottish highlanders were believed not to have progressed beyond the pastoral stage.

Windschuttle argues persuasively that enlightenment views on civil society were what dominated Australian political thinking at the start of the 20th century. The reason it was accepted was that it was a racial theory that found acceptance with the established churches. Unlike Darwinism or its twisted sister Social Darwinism, it posed no conflicts to Christianity and aroused no opposition from the clergy.

All three Australian parties accepted the Policy although many individual politicians spoke against it. The labour groups were most in favour as it ensured that trade unions would not be undercut by imported scab workers. There was also a strong and genuine racist element who supported it. Edmund Barton, the first Australian Prime Minister made a speech during the Policy debate which oozed white supremacy.

But on the whole, Windschuttle is probably correct. The policy was more about realpolitik and cultural views not racist ones. That meant that when the time came to remove it, it was done gradually but without violent opposition at each step. The kind of violence that would undoubtably have occurred if it were racially motivated. All that remains now is a political consensus about the past.

No comments:

Post a Comment