Robert Menzies wrote the Forgotten People in 1942. Donald Horne wrote the Lucky Country in 1964. In the intervening twenty years or so, much of the moral certainties that sustained the country in the early part of the century were blown away by a devastating world war. It was a war that lapped Australia’s shores and confirmed the United States as the dominant western power. The decades that followed saw the emergence of new Australian values. It became a stable, secular and wealthy society driven by conservative mores. The aim of this essay is to examine the factors that contributed to the versions of national identity on view in the Menzies and Horne documents. This essay will examine the similarities and differences in the documents and will show how Australian values changed in the decades between the writing of the documents.

Robert Menzies wrote the Forgotten People in 1942. Donald Horne wrote the Lucky Country in 1964. In the intervening twenty years or so, much of the moral certainties that sustained the country in the early part of the century were blown away by a devastating world war. It was a war that lapped Australia’s shores and confirmed the United States as the dominant western power. The decades that followed saw the emergence of new Australian values. It became a stable, secular and wealthy society driven by conservative mores. The aim of this essay is to examine the factors that contributed to the versions of national identity on view in the Menzies and Horne documents. This essay will examine the similarities and differences in the documents and will show how Australian values changed in the decades between the writing of the documents.The Second World War changed the world’s political landscape and Australia was not immune from the upheaval. The British Empire was permanently crippled. Curtin’s 1941 SOS call to America was answered at a great price. In the post war era “economic, cultural and military dependence on Britain was replaced by a similar dependence on America” (White 1981, p162.) Though Menzies remained a staunch supporter of empire, Horne wrote that Britain’s collapse had perplexed many Australians for whom it was “easier to feel self-important as an imperialist than as a nationalist." Horne was making the point that Australia should now look both harder at itself as well as its local neighbours to better understand the new geopolitical realities around it.

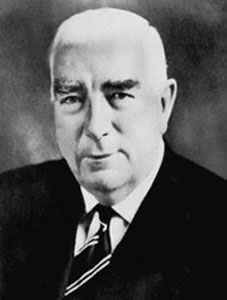

Menzies wrote his Forgotten People radio broadcast during the darkest hours of that war but his subject matter was about the post-war direction of Australian values. The values Menzies favoured were “self-help, independence, freedom, ‘lifters’ rather than ‘leaners’” (Murphy 2000, p137.) These values would be underpinned by Menzies’ motto which was “to strive, to seek, to find and not to yield.” Menzies was describing a spirit of independence, the prototype of what was to be become idealised in the post-war vision of the “Australian way of life.”

The centrepiece of this way of life would be the Australian home. Menzies imagined three types: “homes material, homes human, homes spiritual." The stone walls of the houses were of no use to Menzies unless populated by warm and loving families who combine “dependence upon God with independence of man.” Horne too saw the importance of home in creating a self-satisfied, stable society. But rather than as a result of spirituality, he put it down to the “strong materialistic streak in Australians.” Home ownership was “both a bulwark against communism and the site for happy domesticity” (Murphy 2000, p137.) Both Menzies and Horne construct an Australian identity that the idea of home was the central force in the creation of a stable and conservative nation. Australia embraced this by handing twenty-three years of power to Menzies’s Liberals.

The cultural homogeneity embodied in the idea of universal home ownership led to the embracing of the slogan “the Australian way of life”. Rather than something tangible, it was “a nationalist narrative that served to articulate the various aspirations, values and anxieties” (Tavan 1997, p82) in Australia. Horne recognised the materialistic aspect of these aspirations. Australia was “one of the first nations to find part of the meaning of life in the purchase of consumer goods.” It was an imitation of America which had the way of life which was the “most glamorous, the best publicised” (White 1981, p162.) Horne, who was an admirer of American values, saw this as a positive step. He constructs an image of the growing confidence and sophistication of Australia in the post-imperial world.

The cultural homogeneity embodied in the idea of universal home ownership led to the embracing of the slogan “the Australian way of life”. Rather than something tangible, it was “a nationalist narrative that served to articulate the various aspirations, values and anxieties” (Tavan 1997, p82) in Australia. Horne recognised the materialistic aspect of these aspirations. Australia was “one of the first nations to find part of the meaning of life in the purchase of consumer goods.” It was an imitation of America which had the way of life which was the “most glamorous, the best publicised” (White 1981, p162.) Horne, who was an admirer of American values, saw this as a positive step. He constructs an image of the growing confidence and sophistication of Australia in the post-imperial world.Outside this materialism lay a thin veneer of spirituality. Even in Menzies’s “home spiritual”, God had to share half of this domain with man’s independence. Menzies was sensibly Presbyterian enough not to foist his brand of religion on the people. And even though Anzac Day had its religious aspect, the new religion that most Australians shared was worship of the motor car. The Holden was the first locally built car. Essington Lewis, the wartime minister for munitions and visionary head of BHP, was given the honour of buying the first Holden (White 1981, p164). Homes were an anchor, but it was the growing road network and the cars it supported that gave Australians access to their own country. Motels, imitating the style of their American cousins, started to dot the landscape. Despite the lofty spirituality inherent in Menzies’ speech, it was Horne who best articulated what the Australians were most passionate about: a “pantheist love of outdoor activity.”

Menzies created the Liberal Party in 1944 from the ashes of the United Australia Party (Clark 1969, p255). With the rise of the Cold War, it found its ideological feet with a strenuous opposition to the "officialdom of organised masses." Communists controlled much of the union structure, the state Labor councils and the ACTU (Horne 1965, p.167.) Menzies tried twice to ban the Communist Party but failed both times in referendums. Despite this, the ALP was unable to seize the initiative. It was riven by internal struggles. Bob Santamaria and the Catholic wing broke away to form the anti-communist DLP. The ogre of communism cemented the left in opposition for a generation. Both Menzies and Horne espouse Western values and construct images of Australia which used the mythical way of life to support the conservative status quo.

Since the time of Federation, one of the pillars of that status quo was the White Australia Policy. Keith Windschuttle may well be correct in his assertion that the policy was influenced more by the cultural theories of the Scottish Enlightenment than the racist ones of Social Darwinism (Windschuttle 2004, pp 66-67.) However it was the discrediting of racist ideas after the war that led the policy to fall into disrepair. Immigrants fleeing from the “overt racism” (Murphy 2000, p155) of Nazism could warn Australians of the folly of a race based ethos. The definition of suitable Australians was broadened to include southern, eastern and central Europeans. Further dismantling occurred with the removal of the odious dictation test in 1958. Horne constructs a new idea of Australia, a “suburban nation” where the lifestyle is important, not the racial mix.

In summary, Menzies’s vision for Australia was only partially realised. He brilliantly articulates the community values of a self-help attitude underpinned by the power of the homestead. Alongside a strident anti-communism, it was to be the blueprint for Liberal Party success throughout the fifties and sixties. However, Horne could see other factors changing Australian identity: the decline of empire, the rise of American values, Australia’s growing materialism, the importance of the car and the impact of immigrants. Through the looking glass of these factors it is possible to see a modern Australia slowly emerging.

References

Clark, Manning 1969, A short history of Australia, Mentor, New York

Horne, Donald 1965, The lucky country, Penguin, Ringwood, Victoria

Murphy, John 2000, Imagining the Fifties: Private Sentiments and Political Culture in Australia, University of NSW Press, Sydney

Tavan, Gwenda 1997, "Good Neighbours" in The Forgotten Fifties: Aspects of Australian Society and Culture in the 1950s, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne

White, Richard 1981, Inventing Australia: Images and Identity 1688-1980, Unwin & Allen, Sydney

Windschuttle, Keith 2004, The white Australia policy, Macleay Press, Sydney

No comments:

Post a Comment