Last week was the 35th anniversary of the death of the most prominent Irishman of the last one hundred years, Bono and James Joyce notwithstanding. His name was Eamon de Valera, the American born son of an Irish peasant woman and a Spanish artist. He is little remembered now and mostly reviled in the revisionism surrounding Michael Collins, yet de Valera’s story is nothing less than the story of Ireland for most of the 20th century. (pic of de Valera with Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies taken in London in 1941. Menzies Papers, MS4936. Image courtesy of the National Library of Australia.)

Last week was the 35th anniversary of the death of the most prominent Irishman of the last one hundred years, Bono and James Joyce notwithstanding. His name was Eamon de Valera, the American born son of an Irish peasant woman and a Spanish artist. He is little remembered now and mostly reviled in the revisionism surrounding Michael Collins, yet de Valera’s story is nothing less than the story of Ireland for most of the 20th century. (pic of de Valera with Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies taken in London in 1941. Menzies Papers, MS4936. Image courtesy of the National Library of Australia.)“Dev” dominated Irish politics for 60 years on both sides of the border, was a thorn in the British side for most of that time and also had a massive impact on American affairs over a crucial period between 1918 and 1945. Ireland was such a pain to successive White House administrations, the country was eventually punished for WW2 neutrality by being left out of the Marshall Plan that revitalised allies and enemies alike.

By the late 1950s de Valera’s economy naivete had landed the Irish economy in deep trouble. He was becoming an almost totally blind caricature of the remote and exotic president of the Irish Republic he helped create and then shape in his deeply religious image. Yet he used his aura to cling onto power until 1959 when aged 76 he was forcibly retired upstairs to “the Park”. There as a supposed ceremonial president, he continued wielding enormous influence for two terms and 14 years. He died in 1975 aged 92.

For one day short of 65 years he was married to Sinead de Valera who predeceased him by just three months. Sinead was a long-suffering wife who brought up a large family by herself but who yet held enormous power over her husband in their near-lifetime together. They met through their mutual love of the Irish language and Gaelic was mostly their lingua franca. But it is De Valera’s surviving letters in English to his wife from overseas we see a passion he kept mostly hidden in his public life.

Eamon de Valera’s owed his astonishing longevity of power to a combination of luck, charm and utter ruthlessness and bastardry Ireland has not seen before or since. He owed a large part of his fortune to his birthplace. His Brooklyn mother Cate Coll sent her boy home to her relatives in Ireland after his father the Spanish artist Vivion de Valero lived up to his lothario reputation and moved on. Cate's son grew up in Bruree, County Limerick steeped in west of Ireland culture fused with a British-style education. De Valera was Irish to his bootstraps and changed his birthname George to the Irish Eamon. Nevertheless he used his American birthplace to great effect on many occasions.

Naturally gifted in mathematics and strikingly tall he won a scholarship to one of Ireland’s premier schools, Blackrock College. His leadership qualities stood out and he was a natural captain of the prestigious rugby team. At Blackrock he also forged lifelong alliances with important Catholic prelates who would later rule the country with their croziers as he would with his political cunning.

An avid student of Machiavelli and a deeply Catholic man, he grappled with the rapidly changing political conditions in Ireland at the turn of the 19th century. Queen Victoria was dead and although the Irish still respected the monarchy there was a desire for change. As the Irish home rule movement grew in the south, a Loyalist force in the north grew in opposition. The Loyalists had the support of the top brass of the British Army and the Conservative Party and grew in belligerence and strength as the first decade of the 20th century ended. “Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right,” was their battlecry.

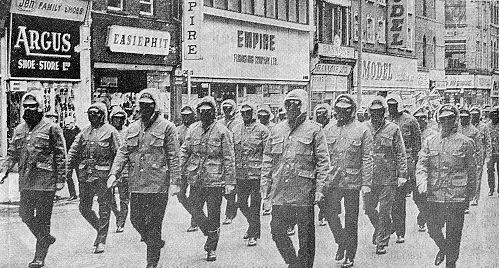

Their cries reached fever-pitch after Westminster finally declared home rule for Ireland in 1912. With the north arming against this outcome with impunity, those wanting Home Rule in the South reacted in kind and set up their own militia groups to defend the likelihood of a Dublin Parliament. De Valera joined the newly constituted Irish Volunteers in 1913 as the Irish arguments threatened civil war in England with much talk of treason. The First World War broke out a year later temporarily putting all arguments on hold. Those on both sides of the Irish question signed up in large numbers to fight for the British Empire in the bloody fields of Flanders and Gallipoli.

Service was voluntary and many like de Valera could not bring themselves to put on a British Army uniform. With the Volunteers falling more and more under the influence of the Irish Republican Brotherhood secret society, a split began among those that stayed behind. De Valera joined the side that was pushing closer to aggression. He rose quickly through the ranks and though suspicious of the IRB was part of the leadership committee that approved the plans to stage an uprising in Easter 1916. De Valera was not one of the seven signatories to the Proclamation of Independence which stated “Ireland through us summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom.” Yet he was one of the key military leaders and was one of the last to surrender a week later when the Easter Rising inevitably failed.

Because he was among the later captives he was held in a different jail to where the other rebel leaders were being summarily executed. By the time of his court martial, the revulsion at the 15 executions over 9 days had swung British public opinion against the execution policy. The William Martin Murphy Irish Independent newspaper was still baying for blood and De Valera was sure he was next. Murphy ensured socialist James Connolly would be the last to be shot while the humble “school-master” de Valera was shuffled off to jail first in Dublin and then four more in Britain. On arrival in Dartmoor he was greeted by other Irish as their leader, the “Chief” by virtue of being the most senior rebel to survive the death squad.

His one rival was Michael Collins who emerged as the new supremo of organisation determined not to repeat the open warfare tactics of 1916. De Valera struck for political status and within a year they were all realised. They went back to Ireland where they organised politically as “Sinn Fein” (Ourselves). With the war going badly and Britain considering conscription in Ireland, Sinn Fein quickly established itself and won most seats in Ireland in the 1918 election. De Valera was elected as the member for Clare.

The British became convinced they were in league with Germany and launched a swoop against of Irish leaders in May 1918. Collins used his spy network to get advance warning but most of the other leaders including De Valera ignored his advice and were arrested. De Valera was sent to Lincoln Prison while Collins began his asymmetric war against Britain striking deadly blows against their vast network of informers which bedevilled Ireland for hundreds of years.

Collins biggest coup was getting de Valera sprung from Lincoln Prison. De Valera was spirited back to Ireland where the pair rowed about tactics. De Valera realised his primary value was as a propaganda weapon and he was smuggled away to the US as the “First Minister” would he would spend 18 months on an awareness and fundraising campaign.

De Valera was treated as a hero by Irish Americans and somewhere along the line his title was inflated to "President of Ireland". But he blundered with his own entry into US politics. He supported the isolationists against President Wilson because he (Wilson) would not recognise Ireland as a participant in the Versailles Peace Conference. He split the Irish-American organisation failing to realise his allies were Americans first and then Irish a long way behind in second. Yet he raised large amounts of money and lots of equally valuable publicity as the war of attrition raged back in Ireland.

Collins was directing that war for the Irish Republican Army against British power with no holds barred on either side. By the time de Valera got back to Ireland both sides were wearying of the bloody stalemate with the Black and Tans offering a particularly savage form of reprisal attacks the Nazis would copy 20 years later. The Protestants in the north used the chaos of the south to form their own administration. Partition of Ireland was first mooted in 1912 Liberal Unionist T.G.R. Agar-Robartes but was rejected at the time but it never went away. The new parliament in Belfast was given the blessing of George V in 1921.

In his speech the King appealed for “forbearance and conciliation” in the South. De Valera was invited to London where he met the Prime Minister Lloyd George. They discussed a possible peace treaty which was only possible because de Valera gave defacto approval of partition. But de Valera knew his countrymen would have difficulty accepting this position. So he cleverly stayed at home for the actual treaty discussions which Collins led with full plenipotentiary powers.

Collins knew just as well as de Valera what was the best compromise he could get. Sure enough in December 1921 he signed a Treaty with Lloyd George that confirmed the existence of Northern Ireland and a new parliament in Dublin with wide powers but one which would have to take an oath of allegiance to the crown. Collins called it the “freedom to achieve freedom”. But he also knew the price he would have to pay. At the signing ceremony senior British Minister Lord Birkenhead told Collins he (Birkenhead) may have signed his political death warrant. “I may have signed my actual one,” Collins replied prophetically.

With Collins and his network exposed, any return to war against Britain would have been doomed to failure. Yet De Valera pretended to be livid with Collins for signing the Treaty to create the Irish Free State. Arguments raged hot over the Oath while the more substantive matter of partition was ignored. The IRA favoured rejection of the treaty while the Church, the newspapers and most of the population wanted peace. De Valera refused to see it as a stepping stone and lent his considerable weight to those against it.

When the Treaty was narrowly carried in the Dail, de Valera held in his hands the fate of Ireland. He resigned as President and offered himself as the leader of the “true Republic”. Hardliners took their cue from “the Chief” and within months Dublin was ablaze again this time in civil war. The war was a hopeless mismatch with Republican idealists no match for British artillery in the hands of Collins’ new army. Collins himself was assassinated in County Cork by a sniper’s bullet while De Valera hid near by.

De Valera never admitted he was wrong but when he indicated that the struggle was unwinnable it quickly ended. He was imprisoned a third time, this time by the Irish. Another year in jail made him realise he could not win by the revolutionary path. He renounced the IRA and Sinn Fein and set up Fianna Fail “the soldiers of destiny”.

After six years of fighting the Oath, he took it himself in 1927 and entered parliament with his new party. The De Valera name had mystique and it did not take long for Fianna Fail to establish as a force. Never forgetting the lesson of the Irish Independent working against him, de Valera went to the States again on another large fundraising mission. On his return he created a new newspaper empire: the Irish Press.

With the power of his name and his new propaganda machine, he was able to form government in 1932. His bitter enemies from the civil war handed over power though rising fascist movements like the Blue Shirts were less accommodating. De Valera ruthlessly dealt with them and later destroyed the IRA when it too looked like causing him problems. He used Collins' stepping stone approach he hated so much in 1921 to gradually remove the Crown from Southern Irish affairs.

Now at the peak of his powers De Valera was Prime Minister (Taoiseach) and Foreign Minister, ably representing the “Irish Free State” at League of Nation conferences. De Valera used the constitutional crisis in England over the abdication of Edward VIII in 1936 to give Ireland a new constitution of his own a year later. It deeply stamped Ireland as a Catholic nation and formally claimed the North as part of Ireland. But like China and Taiwan, this was a fight Dev never wanted to win, he just wanted to keep it going.

In the 1930s he also declared an Economic War with Britain refusing to pay land annuities due to buy out absentee landlords. It lasted six years crippling the Irish economy but caused discomfort in London too. In 1938 he agreed with Chamberlain (whom he greatly admired for his compromise approach) to end the war and resume payments. In return Ireland got back three ports (Cobh and Castletownbere in Cork and Lough Swilly in Donegal) it had given the British Navy in the Treaty. The far-sighted and conservative Churchill (who sparred with Collins in 1921) condemned the deal as he knew the consequences to the defence of the realm in the coming war. It meant De Valera could more easily keep Ireland out of the war that was brewing with Nazi Germany.

When war did arrive, it wasn’t just the British that were exasperated, Roosevelt was equally unhappy. He sent Eleanor Roosevelt’s uncle David Gray as the American Minister in Ireland for the duration of the war. Gray made no bones about openly supporting Britain with the full support of FDR. De Valera hated Gray as an "insult to Ireland" and wanted him replaced. Roosevelt would have none of it.

Particularly in the early days of the war, the lack of availability of the Western Approaches was a bad blow to the British Navy. With the Germans controlling waters in France and Norway, British naval convoys were forced to take a narrow and dangerous channel north of Ireland. Throughout it all de Valera never called it a war. It was an “Emergency” and his young state was on life support. He knew Ireland would have no chance against Nazi bombardment and watched as Belfast across the border suffered some of the worst of the Blitz. De Valera sent the Dublin fire brigade to help put out the fires but never complained to Germany about them bombing "Irish soil".

Despite the efforts of Churchill and the meddling Gray, de Valera refused to bend and as the war progressed, Ireland became less strategically important. Roosevelt's successors did not forget Ireland’s lack of friendship and left the country to muddle economically through the post-war years. De Valera was an economic illiterate and utterly unmaterialistic to the point he promoted hardship as necessary to wellbeing.

By the 1960s he was yesterday’s man despite his enormous status. Managerial types like Sean Lemass and T.K. Whitaker would take Ireland in a new direction that would eventually take fruit in the rise of the Celtic Tiger in 1990s. It was the success of the south that eventually steered the north in the path of peace. Today conditions in the Republic of Ireland are not too dissimilar to what de Valera faced as Taoiseach, rising unemployment, a stagnant economy and mass immigration. But expectations have changed drastically.

The Civil War generation are now long dead. The Irish Press is gone and the Catholic Constitution is almost completely discredited. Even Fianna Fail are in decline though they remain in power 85 years after Dev founded them. Partition of Ireland is entrenched with no prospect of change.

Despite being littered with pettiness, failure and missed opportunities, Eamon de Valera's legacy is immense. Almost single-handedly he developed a positive sense of being Irish to the world that millions both in Ireland and in the diaspora now take for granted. For that and his sheer longevity in power he must still be considered an unrivalled giant of Irish politics.