Thanks to a notification from

Public Polity, I was fortunate enough to hear about the visit to Brisbane of one of the world’s great public transport thinkers Enrique Peñalosa. He spoke tonight in front of a packed audience of 200 people at the Griffith Auditorium in Brisbane’s Southbank about his ideas and experiences. In the invite,

Griffith University described him as an "urban transport revolutionary" who transformed Colombia's largest city from a gridlock of congested streets to a blueprint for sustainable cities.

Enrique Peñalosa holds a BA in Economics and History from Duke University, a master's in management at the Institut International D'Administration Publique, and a Diploma of specialized higher studies (DESS) in Public Administration at the University of Paris II. In recent years Peñalosa has advised governments on urban issues in several developing world cities and currently is Senior Fellow at the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP).

Peñalosa served as Mayor of Bogotá, between 1998 and 2001. During that time Peñalosa revolutionised public transport planning in Colombia’s capital. About the time Peñalosa was elected mayor, Bogotá had a plan to build a series of multi-level highways. Peñalosa realised this was not going to solve the city’s problems and instead would create a huge negative environmental impact. He scrapped the project and for a fraction of the cost built the worlds most advanced

bus rapid transit system called Transmilenio. He also created a network of bicycle and pedestrian pathways that are the envy of most cities of the world.

His speech tonight was entitled “towards a more socially and environmentally sustainable city” and it was sponsored by Griffith University’s

Urban Research Program and the Pedestrian and Bicycle Transport Institute of Australasia (

PedBikeTrans). Peñalosa began by saying his speech would not just be about Bogotá but about cities in general. He described transport as the most complicated issue a city faces. According to the UN, there will be twice as many people living in cities in developing nations in the next 30 years. Peñalosa wondered how sustainable will these cities’ transport policies be? How, he asked, should cities be?

Peñalosa believes the answer to these questions is related to the concept of equality. He defined two types of equality. The first was legal: all people are equal before the law. This constitutional sense of equality has practical implications. For one, it means that public transport should always take priority over private cars. If applied more radically, it could means that cars should be banned entirely. The second equality relates to

quality of life. It means having equal access to public facilities such as schools, hospitals and libraries. The way we organise cities can much to increase this kind of equality. This includes decisions about transport systems and high density housing. But, said Peñalosa, this invites controversy. Talk about public transport is more akin to religion, he said, than engineering.

Peñalosa went on to discuss the impact of the car. Cities have been around for 5,000 years. Cars have been here for the

last 90 years. He said children live in terror of cars and 200,000 children die worldwide each year as a result of car accidents. Yet we accept this as normal. Cars are to children today, he said, as wolves were to children in the Middle Ages. Was this the best we could do after 5,000 years, he asked. Peñalosa said the twentieth century will be remembered as a disastrous one in urban history. After five millennia of planning cities for people, in the 20th century we planned cities for cars. Yet no one goes to France and says “what great highways Paris has”. Peñalosa said that a good city is about pedestrian spaces, which, he said, were the only public spaces available for people. The rest is either privately owned or streets and roads where you are likely to get killed by cars.

These public spaces were a microscopic part of the available land, he said. This lack of space impacts the quality of life. The key ingredient for the growth of society was not capital or land, but people. A city is a collective work of art, he said and we needed to revisit the philosophies of the Middle Ages where they built

gothic cathedrals that took hundreds of years to complete. Where is the thinking today, Peñalosa asked, that asks how a city should look in fifty or one hundred years time?

Peñalosa said there were three key facets to happiness. The first was that people need to be with people. Secondly was the need to walk (or cycle, which is merely a more efficient way of walking) and thirdly was the need to not feel inferior. People need to share their time with their family, not spend three hours every day in a traffic jam. We walk, he said, not to survive but to feel well. But we need attractive places to go. Every great city, he said, has a public space. He mentioned New York’s

Central Park and London’s

Hyde Park where billionaires could mix with homeless people on an equal basis. Peñalosa also said that a good city was one where people want to be outside not inside houses or shopping malls. Malls, he said, were designed to keep the poor out. Good cities that are safe for children, the elderly and handicapped are more likely to be good for everyone else too. To that end, governments needed to make decisions that favoured bicycles and pedestrians over cars.

Peñalosa said it was the number of cars on the road that was the problem, not whether they were polluting or clean. The biggest impediment to life quality is a continual attempt to make room for cars. If at the start of the 20th century transport designers had realised what problems cars were going to cause they would have built a parallel road. But the ‘horseless carriage’ didn’t look like a threat and were allowed to share the space until they eventually took it over. Every city these days, he said, has pedestrianised areas but what if instead of it just being a couple of streets there were 100 kilometres of pedestrianised streets. As mayor, he created 23km of

pedestrian streets in Bogotá. These areas transformed the way that the poor people of Bogotá thought about themselves. Every transport decision, he said, should show humans are sacred. We need to design for human dignity.

Peñalosa also spoke about the sanctity of the waterfront. Waterfronts are so unique, he said, they should never be privatised. And many cities are now

regretting their mistakes of building highways that destroy waterfronts. Engineers used to love building roads next to rivers because there were few intersections. But at the end of the last century, humans realised they have made a stupid mistake. Riverfronts should be pedestrianised, and roads should be on the other side of buildings, not next to rivers.

He then made the observation that transport presents a peculiar problem: it is the only problem that gets worse as a society gets richer. This was clearly not a sustainable model. In developed countries cities are trying to reduce car usage, while cities in under-developed countries are trying to facilitate car use. But more roads do not work. Despite its giant highways, Atlanta is getting more traffic jams each year. In Montreal the

average commute time has increased from 62 minutes in 1992 to 76 minutes in 2005. Only Vancouver, which has not permitted highway development, has decreased travel time. Creating new roads does not work as all it means is that existing cars drive more. New roads generate their own traffic and may solve a problem for a year or maybe two or even five, but will eventually clog up like all the ones before them. Peñalosa said just as the earth going round the sun was counter-intuitive so is the fact more road infrastructure brings more traffic jams.

Under his regime, Bogotá chose not to build the $10 billion highways proposed by Japanese aid organisation

JICA and instead restricted car use. They spent the money on quality public transport and had more than enough left over to improve the lives of the poor on libraries, hospitals and schools. Instead of an eight-lane highway, they built a 35km greenway. Peñalosa said there was no “natural level” of car usage in cities. It was not a decision for traffic engineers but politicians. It’s a simple fact that if you create more space for cars, there will be more cars. Heavy traffic is a signal that a decent public transport needs to be installed.

Peñalosa said that a good public transport system had two critical success factors: low cost and high frequency. He said legislators should not be afraid to force people to use public transport. Parking was not a

constitutional right in any city. Governments have many obligations in areas such as public objectives behind health, education and housing, but not, he said, providing parking on sidewalks. Sidewalks were more akin to parks than streets and were places where people could meet other people.

He finished up with a few other innovations he introduced in Bogotá, such as closing down the city to cars on Sundays and having a ‘tag’ restriction system in place during peak hours. The

Transmilenio buses were designed for heavy load and now carry 1.4 million people every day, funded by a 25 per cent fuel surcharge. He also created a bicycle network from scratch that is now used by 350,000 people daily to commute to work. But he warned that a bikeway that cannot be used by eight year olds is not a bikeway. They are powerful symbols of democracy and play a vital role in constructing community. In advanced cities rich and poor are treated as equals in public spaces. A good city is not made by great highways but by places where eight-year-olds can cycle safely. Peñalosa finished his speech to great applause from the 200 people gathered to hear his wisdom. Let’s hope some of Brisbane’s key decision makers were there. Our transport decision-making remains mired in archaic pro-car 20th century falsehoods.

(Picture credit raintree.com)

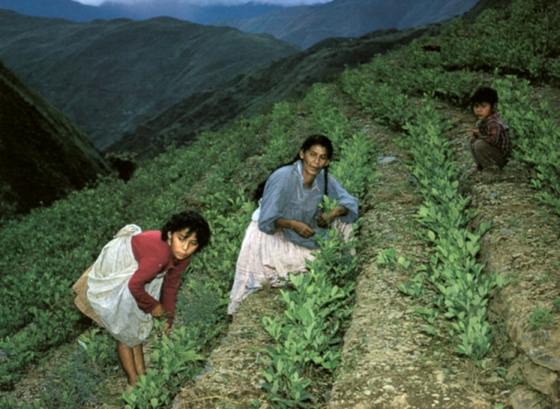

(Picture credit raintree.com) In other early reaction, Colombia’s chief of police dismissed the report’s conclusion that Colombia was the world’s cocaine hub. Oscar Naranjo expressed “great surprise and a series of concerns” over the measurement techniques used by the report. He claimed the UN measurement system is based on information from a French satellite that stopped detecting the scale of illegal crops years ago. Earlier last week, the Colombian authorities said that the country has eradicated 31,000 hectares of coca crops since January, surpassing the amount eradicated in the same period of 2007. This still leaves 70,000 hectares under cultivation if the report is correct and does not take into account any new cultivation. This would appear to be Naranjo’s real “series of concerns”.

In other early reaction, Colombia’s chief of police dismissed the report’s conclusion that Colombia was the world’s cocaine hub. Oscar Naranjo expressed “great surprise and a series of concerns” over the measurement techniques used by the report. He claimed the UN measurement system is based on information from a French satellite that stopped detecting the scale of illegal crops years ago. Earlier last week, the Colombian authorities said that the country has eradicated 31,000 hectares of coca crops since January, surpassing the amount eradicated in the same period of 2007. This still leaves 70,000 hectares under cultivation if the report is correct and does not take into account any new cultivation. This would appear to be Naranjo’s real “series of concerns”.