The polarising influence of Auguste Pinochet is as evident in his death as in his life. Barely hours after he died, thousands took to the streets of Chile’s capital Santiago both to celebrate and mourn his passing. There was a carnival atmosphere in the centre of town where cheering opponents waved flags and sang celebratory songs. But later, clashes broke out when a group of a thousand people marched towards the city's presidential palace. Police fired water cannon and tear gas, while fires raged along one of Santiago's main avenues. Meanwhile Pinochet’s supporters held a vigil outside the hospital where the 91 year old died. One of his supporters told AFP news "it is very sad, because it is as if we were left orphans”.

The polarising influence of Auguste Pinochet is as evident in his death as in his life. Barely hours after he died, thousands took to the streets of Chile’s capital Santiago both to celebrate and mourn his passing. There was a carnival atmosphere in the centre of town where cheering opponents waved flags and sang celebratory songs. But later, clashes broke out when a group of a thousand people marched towards the city's presidential palace. Police fired water cannon and tear gas, while fires raged along one of Santiago's main avenues. Meanwhile Pinochet’s supporters held a vigil outside the hospital where the 91 year old died. One of his supporters told AFP news "it is very sad, because it is as if we were left orphans”.Pinochet died after a suffering a heart attack last week. He underwent a procedure to unblock an artery at Santiago Military Hospital. He had appeared to be recovering until yesterday afternoon when he was rushed into intensive care. He died of heart failure at 14:15 local time, Sunday. "He died surrounded by his family," Dr Juan Ignacio Vergara told reporters. Outside the hospital, his supporters lit candles, waved Chilean flags and held photos of the general. The wake and funeral Mass will be held at a Santiago military academy tomorrow before his remains are cremated. By dying Pinochet has cheated court charges to the last.

In the past year, he was charged with crimes related to his 17 year reign of Chile. He was also charged last with evading taxes on $26 million an investigating judge said he hid in foreign bank accounts. Pinochet had denied defrauding the state during his regime. His lawyers denied in court he had any connection to crimes of violence and also said he deposited his life savings in bank accounts abroad to avoid political persecution in Chile.

Augusto Jose Ramon Pinochet Ugarte was born in the port city of Valparaiso in 1915. He was the son of a Breton immigrant who was a Chilean customs official. He was educated in Valparaiso before entering military school aged 18. After four years of study he graduated with the rank of sub-Lieutenant in the Infantry. In 1943 he married Lucía Hiriart Rodríguez. Together they had five children. Pinochet spent most of the forties slowly rising through the ranks of the army.

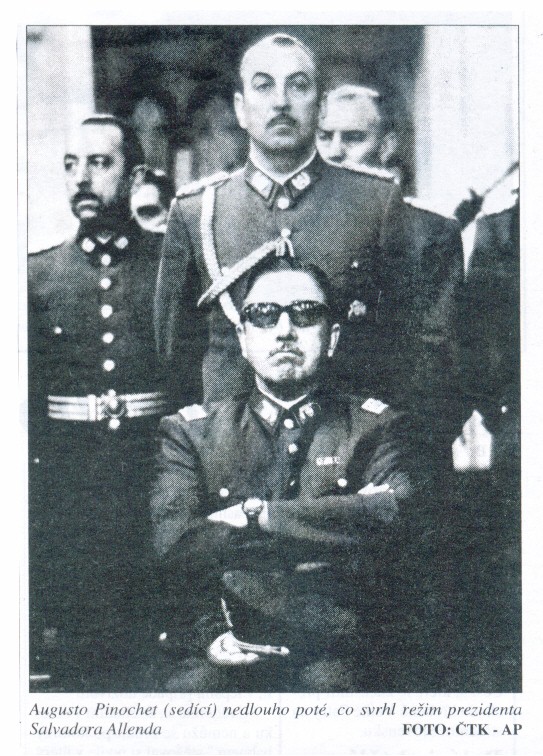

In 1951 he returned to Military School this time as a teacher. He also became editor of Cien Águilas ("One Hundred Eagles") a magazine for army officers. By 1953, he was becoming important. He was now a major and stationed in Santiago as a professor of Chile’s War Academy. He was stationed in Ecuador, obtained a degree and continued to impress his superiors. In 1968 he was promoted to Brigadier General. He joined the masons and was in the same lodge as Salvador Allende. His fellowship with Allende would prove crucial. Allende was elected president in 1970 and Pinochet became General Chief of Staff of the Army one year later. With the US pulling strings in the background, Allende’s government plunged into crisis in 1973. On the day parliament called for his removal, Allende turned to his Masonic brother and appointed Pinochet Army Commander in Chief. Barely three weeks later Pinochet had betrayed his brother and deposed him in a bloody coup d’etat that cost Allende his life.

Pinochet was suddenly in power, the head of a military junta. But he was there at the behest of the US. A CIA document released in 2000 showed that the agency actively supported the military Junta after the overthrow of Allende. Within a year of the coup CIA was aware of bilateral arrangements between the Pinochet regime and intelligence services to track and kill opponents - an arrangement that developed into Operation Condor.

Pinochet was suddenly in power, the head of a military junta. But he was there at the behest of the US. A CIA document released in 2000 showed that the agency actively supported the military Junta after the overthrow of Allende. Within a year of the coup CIA was aware of bilateral arrangements between the Pinochet regime and intelligence services to track and kill opponents - an arrangement that developed into Operation Condor. Pinochet soon consolidated his control of the junta and was proclaimed President in June 1974. The early years of his reign was marked by brutal repression. The socialist, Marxist and other leftist parties that had constituted former President Allende's Popular Unity coalition were all banned. Human rights groups estimate that more than 3,000 people were killed in the first 12 months of the junta’s regime. Santiago's National Stadium was turned into a detention and torture centre. Meanwhile the grim “Caravan of Death” toured the country; it was a euphemism for the mass execution of at least 75 of the junta's highest profile political opponents.

But with the aid of the US, Chile started to prosper economically. Pinochet relied on a group of US trained Chilean economists known as the Chicago Boys. They were market reformers who were trained at the University of Chicago by Milton Friedman. Friedman came down to Chile to preach the values of a free market. But he also told the junta that a free market comes with political freedom. Pinochet ignore that advice, but Chile did push through reforms at a massive price. They privatised the pension system, state industries, and banks, and lowered taxes on income. The country had 30% unemployment but ended up with the fastest growing economy in Latin America.

In 1980, Pinochet approved a new constitution which prescribed a single-candidate presidential plebiscite in 1988, and a return to civilian rule in 1990. Dissatisfied with the long-term promise of democracy, the opposition and trade unions began to organize demonstrations and strikes against the regime in 1983 which provoked a violent response from the government. Pinochet’s leadership survived through the eighties including a failed assassination attempt in 1986 in which five of his bodyguards were killed.

Finally it was time for the long-awaited 1988 plebiscite. In theory this was a rubberstamp vote on a new eight-year presidential term for Pinochet. But a Constitutional Tribunal bravely ruled that the plebiscite should be carried out as stipulated by the Law of Elections. This gave the opposition valuable media space and the President of the Democratic Alliance, Ricardo Lagos, called publicly for Pinochet to account for all the "disappeared" persons. Pinochet lost the plebiscite with 55% voting against him. The result was the beginning of the end for his regime. Pinochet saw that he had no chance of winning an open election and he resigned in 1990. Lagos was appointed president but Pinochet retained his role as the head of the army. He then swore himself in as senator-for-life which offered him immunity from any subsequent prosecution in Chile.

This immunity was put to the test in 1998. An ailing Pinochet travelled to the UK for medical treatment. While he was there, a Spanish judge put out a warrant for his arrest. The charges included 94 counts of torture of Spanish citizens, and one count of conspiracy to commit torture. The government of Chile vehemently opposed his arrest. Pinochet claimed immunity as a former head of state. The case made legal history in the UK going all the way to the House of Lords and making many international law precedents in the process. 16 months later, they decided that extradition could proceed. They decided that former heads of government are not immune from prosecution for crimes committed while in office. The court also affirmed that people accused of crimes such as torture can be prosecuted anywhere in the world But Jack Straw, then Home Secretary made the fateful decision to release him on medical grounds. He returned to Chile and resigned his senatorial seat in 2002, after a Supreme Court ruling that he suffered from "vascular dementia". The ruling was convenient – it meant he could not stand trial for human rights abuses.

Two years later, the Chilean Court of Appeals voted 14 to 9 to revoke Pinochet's dementia status and, consequently, his immunity from prosecution. The decision was confirmed by Chile’s Supreme Court in August this year. But his support at home never eroded until 2005, when undeclared bank accounts held in secret offshore bank accounts containing $US27 million were traced to him and members of his family. But his frail health ultimately came to his rescue. Pinochet died as he lived, untried. Human rights lawyer Hugo Gutierrez told the Chilean newspaper La Tercera Online: "What saddens me is that this criminal has died without having been sentenced and I believe the responsibility the state bears in this has to be considered".

Two years later, the Chilean Court of Appeals voted 14 to 9 to revoke Pinochet's dementia status and, consequently, his immunity from prosecution. The decision was confirmed by Chile’s Supreme Court in August this year. But his support at home never eroded until 2005, when undeclared bank accounts held in secret offshore bank accounts containing $US27 million were traced to him and members of his family. But his frail health ultimately came to his rescue. Pinochet died as he lived, untried. Human rights lawyer Hugo Gutierrez told the Chilean newspaper La Tercera Online: "What saddens me is that this criminal has died without having been sentenced and I believe the responsibility the state bears in this has to be considered".