DR Congo President Joseph Kabila sacked his transport minister yesterday just one day after a plane crash that killed over 50 people in the capital, Kinshasa. A presidential spokesman said Remy Henry Kuseyo was dismissed "due to his inability to reform the aviation sector". On Thursday an Antonov AN-26 owned by Congolese airline Africa One, crashed shortly after take-off and struck a market before ploughing into houses.

DR Congo President Joseph Kabila sacked his transport minister yesterday just one day after a plane crash that killed over 50 people in the capital, Kinshasa. A presidential spokesman said Remy Henry Kuseyo was dismissed "due to his inability to reform the aviation sector". On Thursday an Antonov AN-26 owned by Congolese airline Africa One, crashed shortly after take-off and struck a market before ploughing into houses.Although on board mechanic Dédé Ngamba astonishingly survived the accident by falling out of a hole in the plane into a puddle of mud, at least 51 people have died in Congo’s latest air accident. The Democratic Republic of Congo's air safety record is one of the world's worst and is symptomatic of the larger problems of country ranked second worst in Africa by an independent governance index released this week.

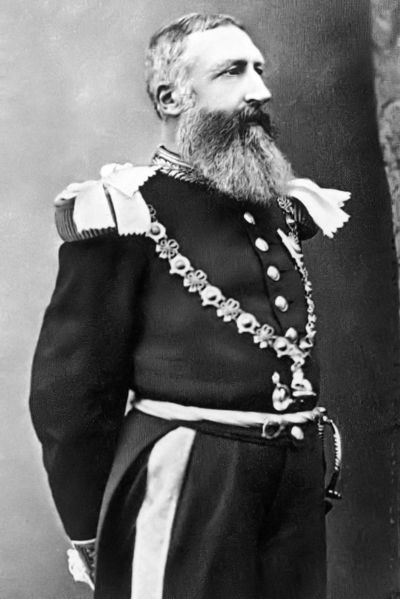

Congo’s issues are daunting. One of the largest countries in Africa, it was created out of nothing over 120 years ago by the greed and megalomania of one of Europe’s most remarkable and most infamous monarchs: King Leopold II of Belgium. Leopold was responsible for the death of ten million Congolese as he built his private empire. The story of Congo and Leopold are told in an excellent book called “King Leopold’s Ghost” by Adam Hochschild published in 1998 and released last year as a greatly condensed film under the same title.

The story starts with a different king: a black one. King Affonso I was ruler of Kongo in the 16th century. He was greatly influenced by the Portuguese traders that plied Affonso’s coastline. He was a moderniser who sought eclectic European ways such as the church, literature, medicine and trade skills. But he didn’t want European rule of law nor did he want mineral prospectors invading his lands. And he could not prevent the rising slave trade for the coffee plantations in Brazil and the Caribbean.

After Affonso died, the power of Kongo diminished. Other countries entered the lucrative slave market. The king of Kongo was beheaded after his armies were finally vanquished by the Portuguese in 1665. An era of European domination was about to begin. Yet for the next two hundred years, the inland would remain mostly off-limits to white eyes. The only route through the thick malarial jungle was by the mighty Congo River itself. But it was a fearsome adversary. Much of the river lies over three hundred metres high on the African plateau. It descends to sea level in just 350kms tumbling over 32 waterfalls.

The man who eventually crossed this natural barrier was born as John Rowlands in Denbigh, Wales in 1841. Rowlands was an orphan who grew up in the workhouse. He was a good scholar fascinated by geography. Aged 16, he sailed to New Orleans where he used his wits to quickly land on his feet and get a job. He also changed his name to Henry Morton Stanley.

The man who eventually crossed this natural barrier was born as John Rowlands in Denbigh, Wales in 1841. Rowlands was an orphan who grew up in the workhouse. He was a good scholar fascinated by geography. Aged 16, he sailed to New Orleans where he used his wits to quickly land on his feet and get a job. He also changed his name to Henry Morton Stanley.Stanley reinvented his past to go with his name and passed himself off as a native-born American.

During the civil war, he signed up for the Confederates but was captured after two days in combat by Union soldiers at the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee. To escape a disease-ridden POW life, Stanley enlisted with the Union Army and finally the Navy until he deserted in 1865. He finally found his metier as a journalist when he covered the Indian wars for a St Louis newspaper. His vivid reports caught the eye of James Gordon Bennett jr, the publisher of the New York Herald and the self described “Napoleon of the Newspaper”.

Bennett offered Stanley a job and sent him to cover the British war in Abyssinia. Stanley was resourceful and he bribed a Suez telegraph clerk to give priority to his reports. As a result Stanley scooped his rivals with news of the conflict. When he got back in London, Stanley thirsted for more success. Bennett in New York gave him a new brief: Find David Livingstone.

Livingstone was a Scottish missionary driven by anti-slavery zeal who wanderings took him across Africa for 30 years. He looked in vain for the source of the Nile, found Victoria Falls, preached the gospel and denounced slavery. In 1866 he went missing on a long expedition and he wasn’t heard from in almost three years. In 1869 Bennett ordered Stanley to mount an expedition to find him. It took Stanley two years to get a 150 man party together and then another eight months before he found his man near Lake Tanganyika. Stanley supposedly greeted him with the immortal four words: “Dr Livingstone I Presume?”

We have to take Stanley’s word on this, as David Livingstone died shortly afterwards in Africa. It was Stanley’s version of events that became history and Stanley himself became an American hero. His book “How I found Livingstone” was an international best seller and one man in Brussels eagerly read in every piece of news about Stanley’s African adventures. That man was 37 year old Leopold II, King of the Belgians.

His father, King Leopold I, died seven years earlier. Leopold the elder was a German prince, related to the British royal family. He was installed as king after Belgium gained its independence from Netherlands in 1830. Leopold II was a French speaker who never bothered to learn the Dutch spoken by the majority of his subjects who lived in Flanders. He was involved in a loveless arranged marriage with Archduchess Marie-Henriette an Austrian Empire Hapsburg.

In his youth Leopold had travelled to Europe, Egypt, India and the Dutch East Indies. His travels whetted his appetite and when Leopold finally took the throne in 1865 he was determined for Belgium to take its part in Europe’s growing colonial adventures. He was not put off by the fate of his younger sister Charlotte who was married off to Austrian archduke Maximilian. Maximilian was imposed as emperor of Mexico by Napoleon III of France. Charlotte became empress and changed her name to Carlotta. Mexicans weren’t impressed by Maximilian and Carlotta and rebelled against their new rulers. Maximilian was executed and Carlotta fled back to Belgium where she descended into madness.

Her brother was slowly cultivating a far more dangerous madness of his own. He was determined to have an African empire. He convened a conference in Brussels which gave rise to the innocuous sounding International African Association. At face value it was an international organisation dedicated to exploration of Africa and the exposure of the slave trade. In reality it was a front for Leopold’s grand ideas of Belgian expansion in Africa. It made enquiries and tried to buy an African colony but none were for sale. It would have to claim one of its own.

While Leopold vainly sought his kingdom, Stanley was also hunting for further African glory. In 1874 Bennett and the London Telegraph sponsored him to cross Africa east to west. His Anglo-American expedition set off from Zanzibar on Africa’s east coast. He arrived at Buma at the mouth of the Congo in 1877. He wrote another best seller “Through the Dark Continent” describing his travels. It also described the great arc traversed by the Congo River that took it on both sides of the equator. The arc exposed the river to a continuous rainy season that contributed to its voluminous water flow.

Leopold avidly followed Stanley’s journey across Africa. He was especially interested in his descriptions of the Congo which was rich in rubber and ivory On Stanley’s triumphant journey back to London, the king lured him to Brussels in 1878. Leopold signed Stanley onto a five year contract. Stanley would lead a Belgian expedition back to the Congo and navigate the river. They would construct a road to get past the fearsome rapids and establish trading posts inland.

Leopold avidly followed Stanley’s journey across Africa. He was especially interested in his descriptions of the Congo which was rich in rubber and ivory On Stanley’s triumphant journey back to London, the king lured him to Brussels in 1878. Leopold signed Stanley onto a five year contract. Stanley would lead a Belgian expedition back to the Congo and navigate the river. They would construct a road to get past the fearsome rapids and establish trading posts inland. For the next five years, Stanley was Leopold’s man in the Congo. After two years they had hauled all their boats and equipment up to the top of the plateau and sailed inland. Stanley was a hard taskmaster and treated Africans with contempt. When he arrived at the opening in the river that bears his name, Stanley Pool, he was shocked to find the French had beaten him there and signed a deal to take the lands north of the Pool. Count Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza had landed north of the river and made his way inland. That land became French Congo and is now the Republic of Congo with Savorgnan donating his name to its capital Brazzaville.

Stanley redoubled his efforts on the south bank of the Congo. He signed deals with 450 Congolese chiefs. Each “treaty” a chief signed gave away sovereignty of their lands to Leopold’s front organisation the International African Association and also committed their people to “assist by labour or otherwise” any “improvements” that the Association might suggest. When Stanley was finished bargaining in 1884, he had “a million of square miles” in the bag. All Leopold needed to do now was to convince Europe to recognise his claim.

Leopold pulled American strings in his pay to lobby President Chester Arthur to recognise the new country. Arthur was a reluctant president. He was vice President to James Garfield in 1880. Garfield was assassinated barely six months into office. Arthur was in poor health and ill prepared for the job now ahead of him. Arthur was flattered into recognising the International African Association’s ownership of Congo. The move was rubberstamped by the European powers in a congress in Berlin in 1884. Leopold sent Stanley as his representative and the explorer was the star attraction. Leopold got his way on the assumption that the Congo was to become a free trade zone.

Suddenly the Belgians woke up to the realisation they had an empire that was 76 times the size of Belgium itself. Leopold called himself the “King Sovereign” of the Congo and by royal decree he renamed his asset the Congo Free State in 1885. It was a private asset and one which Leopold controlled without reference to the Belgian parliament. All profits went to him alone.

Leopold sent Stanley back to Africa on another mission. The governor of Sudan’s southern most province, Emin Pasha,had asked Europe for help against the threat of a Muslim fundamentalist group known as the Mahdists. Despite his exotic title, Pasha was a German Jewish doctor born as Eduard Schnitzer and therefore a white hero in Africa. Stanley’s relief mission went through Leopold’s Congo through unexplored rain forest. By the time they reached Pasha, the crisis was over and Pasha was no longer eager for help.

Despite this failure, Leopold’s empire was slowly consolidating. He established military bases along the river and sent in a team of Belgians to administer his new kingdom and tap into the riches of the rubber trade. Its secret weapon was slavery and used no compunction to shoot villagers if they didn’t obey orders. By the 1890s, American historian George Washington Williams condemned Leopold’s colony as an “oppressive and cruel government” that was guilty of “crimes against humanity. But because Williams himself was black, his warnings were largely ignored in Europe and the US.

Leopold had declared that “all vacant land” in the Congo was to become crown property. He also ignored the free trade edict and had his administrators collect tariffs along the river. They conscripted porters to carry out the ivory to the ports. They were needed particularly to carry the loads past the treacherous rapids until the railway was built. Thousands of porters died of overwork as white overseers enforced discipline with the dreaded chicotte – a hippopotamus hide cut into a sharp-edged cork-screw whip.

Joseph Conrad visited the Congo in 1890 and sailed up river where he saw the horrors of white occupation first hand. Conrad, then a 32 year Polish seaman named Konrad Korzeniowski, initially believed in Leopold’s ennobling mission but was dismayed by his first hand experiences. He spent six months in the Congo and afterwards transformed it into his great book “Heart of Darkness”. It contained an unforgettable portrait of the deranged Kurtz who was based on several Belgian overseers and transformed into an American in Vietnam in Coppola’s Apocalypse Now.

Events in the Congo took a new turn in 1890 after John Boyd Dunlop invented the pneumatic tyre. It set off a craze for bicycles and the world quickly developed an insatiable appetite for rubber. Wild rubber vines were abundant in the equatorial rain forests of the Congo and Leopold was quick to take advantage of the new boom. He went into partnerships with rubber companies to extract the sap. These companies used slave labour to maximise their profits. They rounded up men, chained them together and enforced disciple with chicottes.

The rubber boom gave impetus to construction projects and Leopold worked to finish the railway up the rapids. When completed it added enormously to the state’s wealth and power. But the opening up of the country also exposed his empire to the disinfectant of truth and word was slowly emerging from missionaries of the price paid by locals for Leopold’s enormous wealth. The king was always quick to deny these claims. But one of those that noticed something was wrong, did so from thousands of miles away. His name was E.D. Morel and he was to become Leopold’s most formidable enemy.

Morel was a clerk in Antwerp for a British company Elder Dempster that traded in the Congo. He soon noticed that the only trade into the country was arms and all the material coming out was hardly ever paid for. He realised that only forced labour could account for this. Morel resigned his position and became a full time advocate in against the slave trade in the Congo. He set up his own newspaper the West African Mail to deal with the problem. In 1903, his cause was helped by Irish-born British diplomat Roger Casement.

Morel was a clerk in Antwerp for a British company Elder Dempster that traded in the Congo. He soon noticed that the only trade into the country was arms and all the material coming out was hardly ever paid for. He realised that only forced labour could account for this. Morel resigned his position and became a full time advocate in against the slave trade in the Congo. He set up his own newspaper the West African Mail to deal with the problem. In 1903, his cause was helped by Irish-born British diplomat Roger Casement. Casement travelled to the Congo in his role as Consul to get a handle on the problem. He spoke to overseers, missionaries and natives and he documented his findings in report to parliament. His report showed that abuse, slavery and murder were commonplace. Belgium put pressure on an embarrassed British government to delay publication of the damaging report. Morel meanwhile kept the pressure up for Britain to act for Congo reform. The world’s press began to turn on Leopold and his own sexual indiscretions lost him popularity at home.

Through murder, starvation, disease and plummeting birth rate, Congo was the killing fields of the 1890s and early 1900s. Belgian soldiers launched many punitive expeditions against restless natives and massacres were commonplace. Thousands were held as hostages and died of starvation. Smallpox and sleeping sickness killed many more and as the men were forced into slavery the birth rate dropped considerably. Morel exposed all of these methods of killing.

Leopold launched a massive counter PR operation against the growing tide of evidence. He had a network of paid spies, politicians, businessmen and journalists working in his interests. But when his effort to bribe a US congressman was exposed by Hearst’s New York American newspaper, his rule began to crumble. Under pressure, Leopold launched an independent Committee of Inquiry which issued a damning 150 page report of the state of the colony.

Leopold was forced to seek “the Belgian solution”. He negotiated for the state to take the indebted and scandal ridden colony off his hands. Congo changed ownership in 1908 to the people of Belgium and was renamed “Belgian Congo”. African ownership was not considered. Leopold himself died a year later, unmourned and booed at his own funeral. He had never set foot in the colony he ruled so despotically for over two decades. Forced labour in the Congo continued under the Belgian administration. Belgium itself has tried to brush the whole episode of Leopold’s misdeeds under the carpet.

In 1960 Congo finally won its independence from Belgium. Patrice Lumumba, the country’s new leader, made radical and dangerous speeches that threatened western interests in the country. US President Eisenhower regarded him as a “mad dog” and CIA chief Allen Dulles authorised his assassination. They used Belgians in the Congolese army to support an anti-Lumumba faction and he was arrested, beaten and shot in 1961. The CIA installed Joseph Desire Mobutu who ruled Congo with an iron fist until the bloody revolution of 1997 that deposed him. Congo then survived eight years of wars and four million dead. Though now at precarious peace, King Leopold’s Ghost still haunts the land of Kongo.

In 1960 Congo finally won its independence from Belgium. Patrice Lumumba, the country’s new leader, made radical and dangerous speeches that threatened western interests in the country. US President Eisenhower regarded him as a “mad dog” and CIA chief Allen Dulles authorised his assassination. They used Belgians in the Congolese army to support an anti-Lumumba faction and he was arrested, beaten and shot in 1961. The CIA installed Joseph Desire Mobutu who ruled Congo with an iron fist until the bloody revolution of 1997 that deposed him. Congo then survived eight years of wars and four million dead. Though now at precarious peace, King Leopold’s Ghost still haunts the land of Kongo.

4 comments:

viva the western influence.... again.

Nevertheless, great read, thanks. :)

All new to me. Thanks.

glad you guys got something out of it.

It certainly is a story that very few people are aware of and casts the current situation in a whole new light.

j'aimerai faire ma petite recherche afin de trouer les yeux de ces demons et leurs decescendance pour avoir exterminer atrocement nos arrieres ancetres. Heureusement que ce lucifer chef Leopold est mort comme un chien de la rue. Et nos richesses? ? ? Ils doivent nous les restituer avec interet. ils sont aujourd'hui la source de notre pauvrete.

Post a Comment