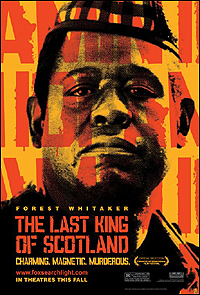

After a clean sweep of the all the lead-up awards, Forrest Whitaker is odds on favourite to claim the Best Actor Oscar for his bravura performance as former Uganda dictator Idi Amin in Kevin McDonald’s film “The Last King of Scotland”. It would be a highly deserved victory. For the role Whitaker spent many months learning to speak Swahili, studying the East African accent and immersing himself in recordings, books, tapes and documentaries about one of Africa's most infamous and bloody tyrants.

After a clean sweep of the all the lead-up awards, Forrest Whitaker is odds on favourite to claim the Best Actor Oscar for his bravura performance as former Uganda dictator Idi Amin in Kevin McDonald’s film “The Last King of Scotland”. It would be a highly deserved victory. For the role Whitaker spent many months learning to speak Swahili, studying the East African accent and immersing himself in recordings, books, tapes and documentaries about one of Africa's most infamous and bloody tyrants.And yet despite his astonishingly accurate and virtuoso performance, played with verve and conviction as a cross between Othello and Titus Andronicus, the Last King of Scotland remains a curiously dissatisfying film. And although it strays considerably from the Giles Foden book of the same name, it is probably the book’s fault that the movie fails to totally convince. The problem is that Foden tells the story of Amin through the eyes of a fictional young Scottish doctor Nicholas Garrigan (played by James McAvoy in the movie) whose becomes Amin’s personal physician by chance. Although the Garrigan is partially based on a real character and Amin definitely played favourites, the doctor’s story only serves to distract attention from the real meat of the tale – Amin’s complex personality and despotic rule.

Amin was born in either 1924 or 1925 in Koboko in the north west of Uganda. His father was a Muslim convert and Idi was sent to an Islamic school where he excelled in reciting the Koran from memory. Uganda was still a British colony in these times and Idi joined the British colonial army towards the end of World War II. He first saw action in 1949 in Somalia where troops were deployed to stop Ethiopian bandits from stealing cattle. He also served against the Kenyan Mau-Mau insurgency in 1952 where he gained his bloodthirsty reputation. Amin was good at sport, became heavyweight boxing champion of Uganda and rose slowly through the colour-biased ranks to become one of the army’s first two black lieutenants in 1961.

Uganda became an independent nation in 1962 and Milton Obote was appointed the country’s first Prime Minister. Although Obote distrusted Amin, he could not afford to antagonise the powerful military man. Obote sent Amin to Zaire to help the rebels fighting against President Mobutu. In return the rebels gave Amin gold and ivory, riches that Amin and the Premier shared, and their friendship blossomed. Amin was appointed army chief. The Ugandan President Mutesa found out about the deal, he tried to sack Obote and institute a parliamentary inquiry. Obote responded by suspending the constitution and giving himself unlimited powers. He promoted Amin to general and commander of the Ugandan army.

Despite this apparent friendship, the two men still heavily distrusted each other. In 1971, Obote planned to arrest Amin on a charge of misappropriating millions of dollars of army funds. Amin found out about the plan. While Obote was out of the country attending the Commonwealth conference in Singapore, Amin staged a military coup.

Obote took refuge in Tanzania where he led a resistance movement and was still considered head of Uganda. Meanwhile, Amin moved to shore up his power going a killing rampage of enemies, real and perceived. Despite the killing spree, most Ugandans initially support the coup, with the charismatic Amin promising to abolish Obote's secret police, free all political prisoners, introduce economic reforms, and return the country to civilian rule.

In 1972, Amin gave the country's 80,000 Asians (mostly Indians and Pakistanis) 90 days to leave the country after receiving a message from God during a dream. According to Amin he was determined to make Uganda "a black man's country". Amin distributed the wealth they left behind to his military favourites. Britain was appalled by his move and immediately stopped aid. Amin looked to Gaddafy’s Libya for help by claiming to turn Uganda into an Islamic state.

The Asian expulsion and lack of aid caused the Ugandan economy to collapse. By 1975 he had killed up to 500,000 people whose misfortune was to belong to the wrong tribe or supported Obote. Amin personally ordered the execution of the Anglican Archbishop of Uganda, Janani Luwum, the chief justice, the chancellor of Makerere College, governor of the Bank of Uganda, and several of his own parliamentary ministers. He launched a huge personality cult around himself and pronounced himself King of Scotland.

The Asian expulsion and lack of aid caused the Ugandan economy to collapse. By 1975 he had killed up to 500,000 people whose misfortune was to belong to the wrong tribe or supported Obote. Amin personally ordered the execution of the Anglican Archbishop of Uganda, Janani Luwum, the chief justice, the chancellor of Makerere College, governor of the Bank of Uganda, and several of his own parliamentary ministers. He launched a huge personality cult around himself and pronounced himself King of Scotland.Back in the real world, things were starting to get ugly. In 1976, the PLO hijacked an Air France flight that originated in Tel-Aviv. Amin was sympathetic and personally invited them to bring their cargo to Uganda. They landed at Entebbe international airport where the hijackers and hostages were addressed by Amin and where they had the co-operation of the Ugandan army. After negotiations broke down to release the Israeli hostages, the Israelis launched an airborne assault on the airport to free the hostages as well as killing the hijackers and 27 Ugandan troops at the cost of one dead Israeli. This successful attack on home soil was a serious embarrassment to Amin.

But it didn’t stop his expansionist aims. In October 1978 Amin attempted to annex Kagera, the northern province of neighbouring Tanzania. Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere mobilised his army reserves and counterattacked. They were helped by a united Ugandan opposition group in exile called the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA). Despite aid and 3,000 troops from Gaddafy’s Libya, Amin’s troops were beaten back. The Ugandan army finally fled leaving the Libyans ward off the attack. Tanzanian and UNLA forces met little resistance, and invaded Uganda, taking Kampala in April 1979. Amin fled to Libya leaving the UNLA to unravel as it fought among themselves to take control of the country. In 1980 the new leaders held an election and Milton Obote was returned to power.

Meanwhile Amin stayed as a guest of Gaddafy for almost ten years, before finally relocating to Saudi Arabia. On 16 August 2003 Idi Amin died in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The cause of death was 'multiple organ failure'. Although the Ugandan government gave permission for burial in Uganda, he was quickly and quietly buried in Saudi Arabia. He was never tried for gross abuse of human rights.

Meanwhile Amin stayed as a guest of Gaddafy for almost ten years, before finally relocating to Saudi Arabia. On 16 August 2003 Idi Amin died in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The cause of death was 'multiple organ failure'. Although the Ugandan government gave permission for burial in Uganda, he was quickly and quietly buried in Saudi Arabia. He was never tried for gross abuse of human rights.In the Last King of Scotland, the story ends well before Amin’s death and the climax is more about the escape of Dr Garrigan. The closest thing Amin had to a real British friend and adviser was Bob Astles. Astles was English and about the same age as Amin. Like Amin, he served in the British army. Aged 21, he came to Uganda seeking adventure and wealth. He set up the first airline to employ Ugandans and married twice, the second time to local royalty. Although initially an Obote supporter, he changed allegiances to Amin after he was arrested and tortured. In 1975 Bob Astles formally joined Amin's service, becoming the head of the anti-corruption squad and an advisor on British affairs. Known as “the white rat” he was a feared man until the Tanzanian invasion. The invaders charged him with murder and corruption and he served six years jail. He returned to Britain in 1985 and now lives in the genteel surrounds of Wimbledon.

Giles Foden interviewed Astles for the book of the Last King of Scotland and used much of his back-story to fill in the details of the fictional Garrigan. But the decision to turn Astles into a young Scottish doctor is not entirely successful. As Kam Williams says “the novel is narrated by a fictitious character purely a creation of Foden’s imagination, a naive Scottish doctor with an uncanny, Forrest Gump-like knack for appearing at memorable moments in Ugandan history.”

No comments:

Post a Comment